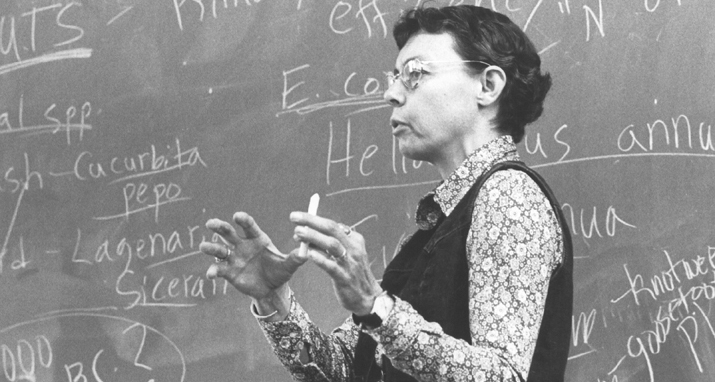

Patty Jo Watson

Tara Eavy

Early Life

Patty Jo Watson was born in Superior, Nebraska early in the days of the Great Depression. She had not been interested in cave archaeology as a child and spent little to no time near caves at all. Instead, she climbed windmills, swam in horse tanks, and participated in every extracurricular activity that her high school offered. But one day in Sheffield, Iowa’s public library she read Dame Agatha Christie’s Come Tell Me How You Live (1946) which was an account of Christie’s experiences on archaeological excavations in Syria and Iraq during the 1930s. This, Watson insists, was the catalyst for her interest in archaeology. Initially, she was a premed major at Iowa State College but eventually decided to pursue a graduate’s degree in anthropology and enrolled in the University of Chicago’s anthropology premasters program in 1952.

While in the premaster program in Chicago she gained interest in Robert J. Braidwood’s Irag-Jarmo Project, a long-term project focused on recovering early remains of domesticated plants and animals in the fertile crescent. In the summer of 1953 she attended the University of Arizona’s Point of Pines field school where she gained an interest in floatation techniques for recovering botanical remains. The following academic year, 1954-1955, Watson participated in the Iraq-Jarmo Project for a nine-month field season in the Zagros Mountains of Northern Iraq. Here, as a field assistant to Robert Braidwood., she identified and recovered both floral and faunal remains with intentions to determine the origins of agriculture and pastoralism in the Near East.

Watson received her master’s degree in 1956 and doctorate in 1959. During this time, because of worsening political turmoil in Iraq, research was shifted to Northern Iran where Watson served as an archaeological assistant focused on ethnoarchaeological research on various living villages near the expedition’s headquarters. After her return from Iran she was employed as an instructor of anthropology at the Universities of Southern California, California, and Los Angeles State all located in Los Angeles. It was not until 1963 that Watson’s focus finally shifted to North American archaeology, more specifically the Salts and Mammoth cave systems in Kentucky. Watson and her colleagues explored deep into the caves and found evidence of Native American activity including mining activity, desiccated bodies, pieces of textiles, and faunal remains. Her findings here inspired the creation of the Shell Mound Archaeological Project (SMAP) which studied cultivated faunal remains in the Green River area of Kentucky.

In 1968 Watson was hired to teach anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis and continued to work there until her retirement in 2004. During those 32 years she taught at Washington University and conducted extensive fieldwork in Turkey.

Archaeology Career

Patty Jo Watson received her M.A. in Anthropology from the University of Chicago in 1956 where she wrote her Master’s thesis, “New Material from Northern Iraq: The Halaf ‘Period’ Reconsidered.” There were large challenges to undertake to continue fieldwork in northern Iraq and Iran during the 1950s, but this did not deter archaeologists seeking to excavate, analyze, and interpret archaeological evidence for origins of domestication in the Old World. Dr. Watson also received her Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Chicago in 1959 after she finished her work examining “Early Village Farming in the Levant and its Environment.”

Dr. Watson’s initial experiences with fieldwork came during her time with the Iraq-Jarmo Project while she was a student of the University of Chicago. In the 1950s she worked with Neolithic artifacts from the Jarmo site in Iraq and pioneered the use of ethnoarchaeological analogy, utilizing results of excavations to recognize the extensive cultural continuity from past to present in that part of the world. It was with Robert Braidwood that she undertook these investigations into how prehistoric food-producing communities functioned during the early Holocene period in western Asia. Her findings from the Middle East excavations and research would be the basis of her Ph.D. dissertation and countless articles, essays, and compositions to follow. The outcomes of her fieldwork on Neolithic cultures in the Middle East are published in the reports on Jarmo and Girikihaciyan. Evidence of faunal and floral domestication in the Old World inspired her interest in the origins of plant domestication in the New World.

She found, in the dark forgotten passageways of the Salts Cave segment of Mammoth Cave, vital clues to the history and nature of early domestication. Dr. Watson headed numerous survey and charting expeditions in both the Mammoth Cave and Jaguar Cave systems. A record of this work is contained in The Prehistory of Salts Cave, Kentucky, which was published in 1969, and in Archaeology of the Mammoth Cave Area, published in 1974. These underground findings would be combined with archaeological surveys and excavations done at the shell mound sites along the Green River in Kentucky. Watson collected data from within and outside these caves which has been summarized in professional papers and articles that represent a more complete map of the diversity and sequence of faunal domestication in the eastern United States. One such compilation of this work is titled Of Caves and Shell Mounds, in which Watson and her students outline the evidence accumulated by decades of research. Eventually, with the collaboration of Julie K. Stein, Darcy Morey, and George Crothers further archaeological work was done on this area as part of the Shell Mound Archaeological Project (SMAP).

Her research focus shifted from the eastern United States to the southwestern United States during 1972 to 1974, when she helped to codirect the Cibola Archaeological Research Project. Watson’s work at Cibola was primarily fixated on investigating a large pueblo site related to the Zuni nation. It was here that held the fertile ground perfect for testing hypotheses concerning ceramic production, decoration, and evolution within complex New World communities. But decades of North American fieldwork only added time and skill to her interest in the Old World. From the years 1991 to 1994 she consulted for the Xiaolangdi Dam Salvage Archaeology Project at Bancum in the People’s Republic of China where her contributions came in the form of expertise in flotation recovery, precision in sampling and interpretation, and ethnoarchaeological documentation.

Dr. Watson has written articles for many a publication, including American Anthropologist, The School of American Research, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science,Archaeology magazine, Expedition, and the World Book Science Annual. These are only a handful of publishers for her work. She has written countless more dissertations about her work in the both the Old World and the New World. These can be bought online or in many major bookstores.

Major Contributions to the Field of Archaeology

Patty Jo Watson led the way for the development of ethnoarchaeology, cave archaeology, and archaeological gender studies, and forward-thinking practices for the recovery of organic materials from excavation sites. Her refinement and application of flotation technology allowed archaeologists to recover small items, including archaeobotanical and archaeofaunal materials, within a scope they had not previously thought possible. Her paleobotanical research in Salts Cave, Kentucky changed forever the way in which we defined agriculture in Eastern North America and set a high standard for succeeding research in both the New and Old Worlds.

Concerning this, very few scholars have made so many noteworthy contributions to research in two such diverse areas of the world. In addition to her studies of early agricultural communities in Eastern North America, Professor Watson has conducted groundbreaking research in the Middle East. This research and her consequent studies in Northern Iraq, Iran, and Turkey anchor much of our knowledge of Western Asia’s history as the earliest center of agricultural domestication.

Dr. Watson’s contributions to archaeological theory alone represent a major involvement with the evolution of archaeological understanding. These contributions include her still significant Explanation in Archaeology: An Explicitly Scientific Approach (New York 1971), Archaeological Interpretation (New York 1986), and a set of more recent documents such as “A Parochial Primer: The New Dissonance as Seen from the Midcontinental United States” and “The Razor’s Edge: Symbolic-Structuralist Archaeology and the Expansion of Archaeological Inference” (American Anthropologist 1990). In thinking about the role of science in archaeology and archaeological inference, Watson remains at the forefront of the discipline whilst consistently maintaining a commitment to interdisciplinary perspectives.

Some of her greatest contributions, though this may be pertinent to only a small group of people, have come in the form of her expert mentorship. Watson has long assimilated students into both her field and laboratory settings for hands on experience, teaching excellently in both large and small class settings during her many years at Washington University in St. Louis (1969–2005). Students and faculty speak highly of her patience and genuinely tireless dedication to evolving our knowledge of the past.

Legacy