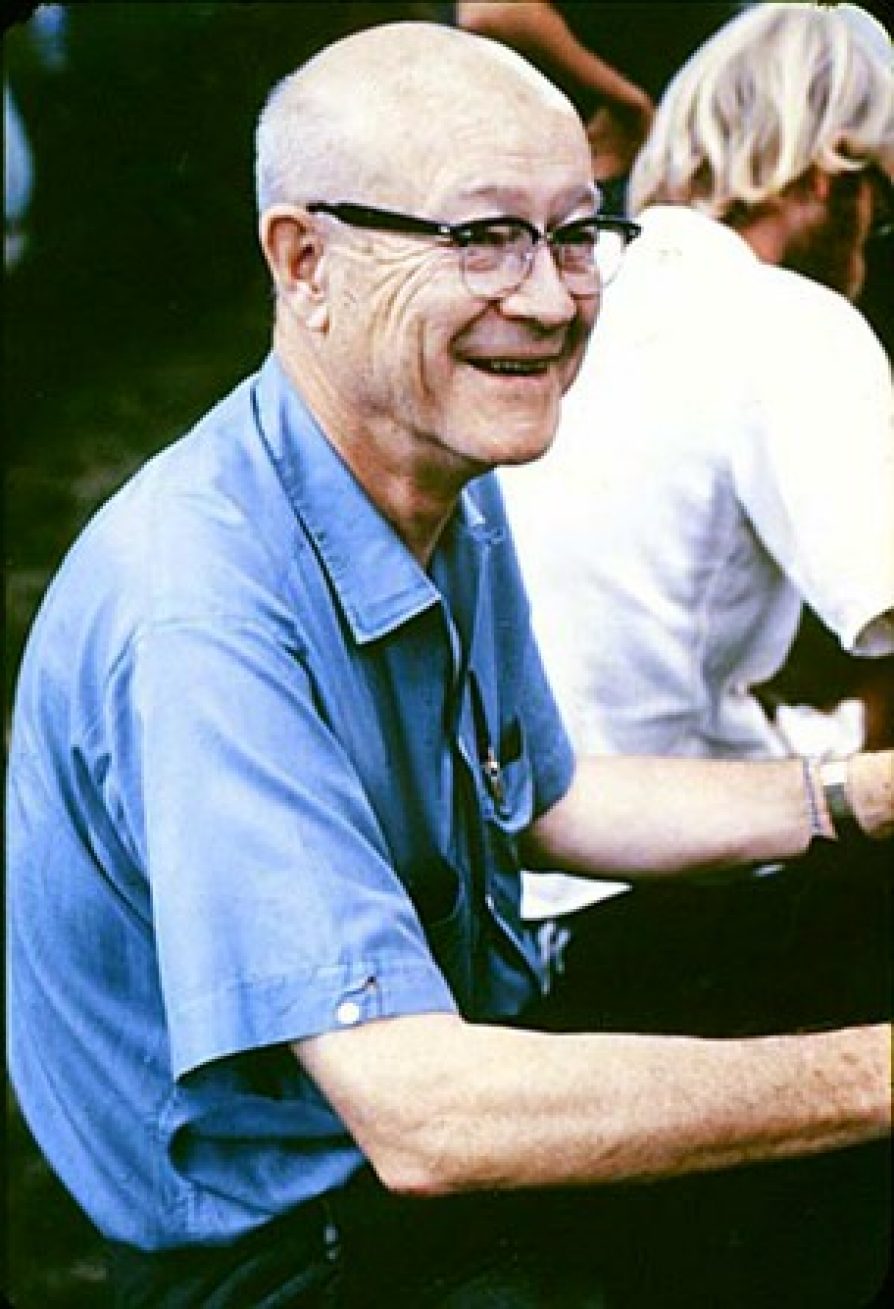

James B. Griffin

Aleksandra Popovic

Early Life/Biography

James “Jimmy” Griffin (1905-1997) is considered to be one of the most influential North American archaeologists in the 20th century. He was born in Atchison, Kansas, on January 12, 1905 to Charles and Maude Griffin. His family first moved to Denver, Colorado, and then to Oak Park, Illinois, where he spent the majority of his childhood. Most of his teenage years were spent as a cheerleader and swimmer for Oak Park and River Forest High School. Being raised in the traditions of the midwest, loving to read and visit museums. Ultimately, this is where Griffin’s fascination for archaeology blossomed.

In 1923, Griffin attended the University of Chicago, where he began studying Business Administration. After two years, he switched to General Science, in which he received his Bachelor’s Degree. He gained excavation experience in the Illinois Field School of the anthropologist Faye Cooper Cole in the summer of 1930, and this fieldwork then led to one of his first, of many, publications. Later that year, Griffin received his Master of Arts from the University of Chicago with a thesis on mortuary variability in Eastern North America.

During the time of the Great Depression, there were few positions open for young, up and coming archaeologists. Griffin sought positions in Pennsylvania, Hawaii, Guatemala, and Iraq, each with varying successes. However, in 1932, Griffin was fortunate enough to find a research fellowship for which he would be in charge of the North American ceramic collections at the University of Michigan’s Museum of Anthropology. In February 1933, Griffin moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, and received his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan in spring 1936.

Griffin married his first wife, Ruby Fletcher, that same year, and they had three sons together, John, David, and James, all raised in Ann Arbor. Griffin spent 5 decades in Ann Arbor, going from graduate student, to professor, to director of the Museum of Anthropology, for which he served three decades as this position. He even spent the first years of his retirement in Ann Arbor, but moved to Washington, D.C. in 1984, several years after his wife's death in 1979. In D.C., he met and married his second wife, Mary DeWitt, whom with he spent more than a dozen together. In Washington is where he became a Regent’s Scholar in the Department of Anthropology at the Smithsonian until his death. James Bennett Griffin died quietly in his sleep in Bethesda, Maryland, in the loving company of his wife and his sons on May 1, 1997.Griffin was best known for being the man responsible for reshaping the archaeology of Eastern North America, for building a center for long term cultural change at the Museum of Anthropology of the University of Michigan, and for fostering many innovations in archaeological method and theory throughout his long career.

Archaeological Career

Griffin began training in field archaeology at the University of Chicago. He gained his first fieldwork experience during the summer of 1929, under the direction of William Krogman. This field work consisted of a survey of Adams County, Illinois, and excavation at the Parker Heights Mound near Quincy, Illinois. By summer 1931, Griffin had gained enough training to conduct his own excavations in the Upper Susquehanna Valley, Pennsylvania, for the Tioga Point Museum. He had to cancel a second season in 1932 because of Depression caused budget cuts.

In fall 1940, Griffin joined Jim Ford and Phil Phillips in the Lower Mississippi Survey project. Between 1940 and 1946, he spent three field seasons conducting surface surveys, while Phillips carried out stratigraphic excavations. Hundreds of sites in the Lower Mississippi Valley were systematically recorded and the recovered ceramic fragments were grouped into units using statistical and graphical techniques. Griffin and Phillips attempted to assign a chronology to their lower valley based on the association of sites with prehistoric meandering channels of the Mississippi River, to which absolute dates had been given based on changes evident on dated maps from the past three centuries. Although their dating results were found to be slightly inaccurate, their in depth approach in excavation was still radically more thorough than those others of its time.

In 1946, Griffin was appointed director of The University of Michigan’s Museum of Anthropology. That same year he spent six months in Mexico working in the Museo de Antropología in Mexico city. There he shared his ideas about the categorization of Mesoamerican ceramics, along with studying the collections and visiting the sites of and near Mexico City. Griffin viewed this time as a means of expanding archaeological ideas and approaches, both through the University of Michigan museum and through the places he visited.

In 1949 he became a professor in the department of anthropology where he influenced the careers of many new archaeologists. During his years as a professor and director, Griffin expanded many of his ideas and promoted an interdisciplinary approach to the study of archaeology.

Even as a director and professor, he continued to influence fieldwork, now in the Central Mississippi Survey. This survey’s major focus was at Cahokia, but other fieldwork was done in southeast Missouri and at the Roots site near the Kaskaskia River. Although these activities continued through 1952 and 1953, Griffin was no longer directly involved.

In 1961, Griffin’s interests in the Siberian roots of North America led him to travel to visit Poland and Russia. There he explored many sites and museums and expanded his knowledge of the European approach to studying archaeological sites, based on environmental context. He also launched collaborative projects with his friends in Poland and Yugoslavia. During this time he also became a United States representative to the International Union of Pre- and Protohistoric Sciences.

It is apparent that Griffin’s primary involvement in field activities shifted to a broader, more general study and overview of archaeology in terms of cultural change. In 1963 and 1964 he supervised excavations at the Norton Mound group of Hopewellian affiliation in Grand Rapids, Michigan. The proposal for this project was one of the first National Science Foundation grants ever awarded to an archaeological project. As a supervisor to this project, Griffin applied and interdisciplinary approach, calling together geologists, ethnobotanists, paleobotanists to cultivate information. This resulted in a study focused on human ecology, artifact variability, and social organization, which marked a transition toward a new approach to archaeology in America.

A few years later, he was encouraged by one of his students to return to the northern end of the Lower Mississippi Valley with the Powers Phase project in southeast Missouri. Here is where successful new field and collection techniques provided Michigan students with an innovative field experience, such as the one Griffin had had in Illinois nearly 40 years before.

By the early 1970’s, Griffin’s primary involvement was in projects designed to provide data to classify the major communities of the Mississippian cultures as chiefdoms, or cultures with power given to a single person. Griffin was skeptical about this idea, so he performed a strict assessment of it based on settlement excavation with prolonged plotting of artifacts in and around houses, and screening and floating for subsistence remains, which could show the enduring differences in social rank through to characterize chiefdom. Griffin’s last years were spent as a Regent’s Scholar at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington D.C. Here he worked on synthetic articles and overviews of conferences.

Major Contributions

One of Griffin’s biggest contributions to the field of archaeology was his binomial system for classifying artifacts. Until the mid 1940’s archaeological assemblages were classified by their ethnic groupings, which were mainly known to archaeologists by their descriptions by European explorers. This system was flawed because many different ethnic groups were found in overlapping excavation regions. Griffin believed that the classification of artifacts should be done strictly based on their archaeological features, without the biased reference to ethnic groupings.

As more and more artifacts began filling Michigan’s Ceramic Repository to be described and classified, Griffin began his systematic classification. He began with large groupings of sherds and categorized them based on clay body and inclusions and then subdividing them into smaller groupings based on surface treatment and decoration. This binomial system of classifying artifacts became a primary form in typology and is still greatly used today.

Another of Griffin’s contributions was his ability to foresee changes in the field of archaeology, and applying those changes to the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology. In the 1960’s when archaeology began to shift from a cultural and historical approach to a processual one, the institution changed from one that revolved around North American culture to one that researched cultural evolution to this day. Griffin brought in curators, researchers, statistical analysts, and computerized data programmers to aid and to apply a multidisciplinary approach to the transition. The museum transformed into a center for new developments in processual and postprocessual archaeology.

Griffin's other research activities are much better known through his large number of publications (more than 260) and especially through his three major syntheses: the first in a volume edited by Frederick Johnson, a second in his festschrift for Fay Cooper-Cole, and the third in Science. While this last synthesis was one of his most cited publications, it was the first to really bring him to the attention of North American scholars. Indeed, Griffin had worked on this synthesis from 1936 on, giving versions of it at numerous professional meetings. His last formal presentation of this paper was at the 1941 meeting of the American Anthropological Association, and it was only because of World War II that publication of this seminal work was delayed until 1946.

Legacy

Griffin’s legacy can be viewed by the many awards he received. He was one of the most honored archaeologists of his time. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1968. He received the Viking Fund Award and Medal, the Fryxell Award, and the Distinguished Service Award from the Society of American Archaeology, which he helped found in 1935. He was elected Special Honorary Fellow of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. He was honored with the Distinguished Faculty Achievement Award and the Henry Russel Lectureship for outstanding research from the University of Michigan, along with naming him one of its ten most distinguished faculty members. After his retirement, two festschrifts were presented to him to honor his time as an educator.

During his years at the University of Michigan, Griffin influenced many archaeologists who went on to have their own distinguished archaeological careers. His research and teaching at the University of Michigan turned the institution into one of the nation's foremost training grounds for American archaeologists. By the 1980’s, Griffin’s students were teaching at most of the major archaeology graduate programs in the country. Even today, it is difficult to find a specialist in Eastern woodlands who was not directly influenced by Griffin. His legacy as an educator is considered to be one that was helpful, caring, and directly honest.

Griffin’s influence was also recognizable not only nationally, but globally. He was constantly visiting new countries, sharing his knowledge, learning new about methods of analyzation, and bringing those methods back to the United States. His actions cross-nationally have helped shaped today’s global network of archaeologist.

In today’s times of growing agricultural technology and suburban sprawl, the destruction of irreplaceable archaeological sites has become an increasing issue. Griffin was a profound advocate for the betterment of the field of archaeology. If something can be learned from his career today, it would be to fight for the conservation of sites, the integrity of museums and university programs, the funding of fieldwork, and the criticism of theories that are not supported by hard evidence. Griffin ultimately helped guide the field of archaeology through a time of transition. His influence is prevalent to this day, apparent by his accomplishments and contributions to the field. He has greatly evolved the archaeological community and his wit, thoroughness, and curiosity continues to influence future archaeologists to this day.

References

1. "The Griffin Years: 1944–1975." College of Literature, Science, and the Arts. University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology, 2016. Web. 05 May 2016.

2. Williams, Stephen, and Vin Steponaiti. "James B. Griffin1905-1997." SAA Bulletin 16(1): James B. Griffin, 1905-1997. Society of American Archaeology, n.d. Web. 05 May 2016.

3. Wright, Henry T. "James Bennett Griffin." James Bennett Griffin 1905—1997 (n.d.): n. pag. Nasonline.org. National Academy of Sciences. Web. 5 May 2016.

4. "James B. Griffin." College of Literature, Science, and the Arts. University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology, n.d. Web. 05 May 2016.

5. "James B. Griffin Papers 1922-1997." Quod.lib.umich.edu. Bentley Historical Library, n.d. Web. 5 May 2016.

6. "GRIFFIN, JAMES BENNETT, 1905." Anthropology and Archaeology. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, n.d. Web. 05 May 2016.

7. Griffin, James B. "AN INDIVIDUAL'S PARTICIPATION IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY, 1928-1985." Annualreviews.org. Annual Reviews Anthropology, 1985. Web. 05 May, 2016

Images

1. James B. Griffin. University of Michigan. http://um2017.org/faculty-history/sites/default/files/imagecache/small/Griffin,%20James.jpg. Web. 2 May, 2016.

2. Griffin, James Bennett at excavation. University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology. https://lsa.umich.edu/ummaa/about-us/history/the-griffin-years--19441975/jcr:content/par/textimage/image.transform/xbigfree/image.jpg. Web. 2 May, 2016 .

3. Griffin, James Bennett. Dig at Starved Rock, IL ca.1948 University of Michigan Bentley Image Bank. http://bentley.umich.edu/legacy-support/anthropology/images/griffdig.jpg. Web. 2 May, 2016.

4. Griffin, James Bennett. Museum of Anthropology staff outside of museum, 1974. University of Michigan Bentley Image Bank. https://lsa.umich.edu/ummaa/about-us/history/the-griffin-years--19441975/jcr:content/par/textimage_317291536/image.transform/xbig/image.jpg. Web. 2 May, 2016.

5. Griffin, James Bennett. Society of American Archaeology. http://www.saa.org/portals/0/saa/publications/saabulletin/16-1/art/griffin.jpg. Web. 2 May. 2016.