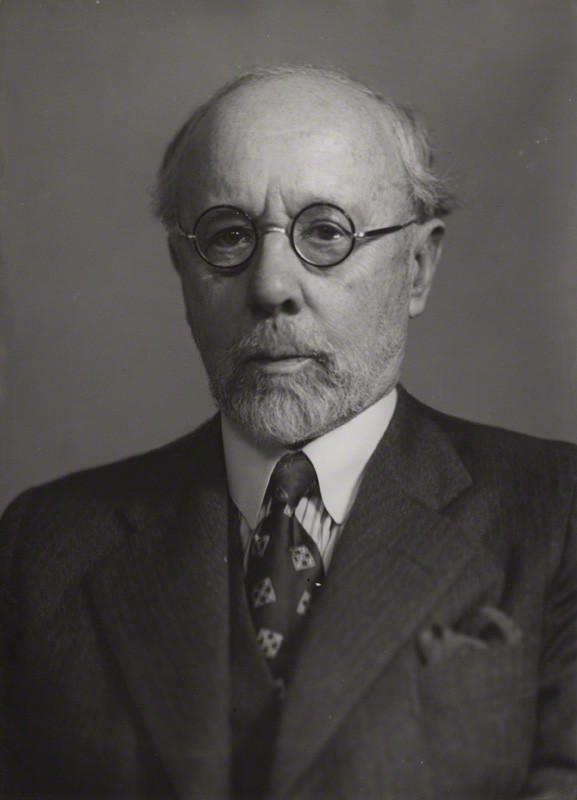

John Garstang

Siana Stanton

Early Life

John Garstang was born on May 5th, 1876 in Blackburn, Lancashire to Walter Garstang and Matilda Mary Wardley. John was the sixth child born of the physician and his wife. He attended Blackburn grammar school, where he was especially interested in astronomy and the classics. However, Garstang was forced into specializing in mathematics. In 1895 he acquired a scholarship to study mathematics at Jesus College in Oxford. While making visits to the observatory at Stonyhurst College, he often passed the ruins of the Roman camp located in Ribchester. It was those ruins that sparked Garstang’s interest in archaeology; he excavated them and published his findings in 1898. It was while conducting those excavations that he was acquainted with F.J. Haverfield, a leading scholar of Romano-British archaeology. It was Haverfield who really encouraged Garstang to pursue archaeology. While still studying mathematics as an undergraduate, he spent his vacation days excavating archaeological ruins. In 1907 he married Marie Louise, and they had one son and one daughter.(Gurney, 2004)

Archaeology Career

After obtaining a degree in mathematics, Garstang worked with Flinders Petrie in Egypt at Abydos in 1900. There he excavated sites such as Abmyeh (1900) and Beyt Dawd (1901-1902). His first great discovery was the great tomb at Beyt Khallaf in 1901, and he later was provided with funds for its excavation. Garstang continued his work in Egypt where he led expeditions at sites such as Negadeh (1902-1904), Beni Hasan (1902-1904), Heirakonpolis (1904-1905), and Esna (1905-1906). At each of these sites, Garstang was studying the burial habits of the Egyptians. He concluded that in Egyptian culture the best of the sculptures, paintings and architecture were left in the tombs for the deceased to enjoy in their afterlife. It struck him that throughout the eventful history of the Egyptians, the one thing that remained constant in their religion was the care that they took of their dead (Garstang, 1907) .

It was Garstang’s lifelong friend Archibald Henry Sayce that prompted some of his most important and prestigious work. It was Sayce that first got Garstang interested in the Hittites, and in 1904 he took off to the Asia Minor for archaeological exploration. In 1907 Garstang obtained a permit to excavate the Hittite capital of Boghazköy with his leadership of a British expedition. However, when they arrived at Constantinople they learned that their permit was transferred to Hugo Winckler by the German emperor. Garstang then had no choice but to make a second exploratory journey through Asia Minor to find another Hittite site to excavate. The next year he selected the site of Sajke-guezi for excavation, and in the winter months he continued to explore the tombs of Abydos. It was Garstang’s work in the area that is now modern Turkey and Syria that helped to rediscover the almost forgotten civilization of the Hittites (Sayce, 1923). The Hittites were the chief power and cultural force in Western Asia from 1600 to 1200 B.C. They were referenced in the bible as a powerful military force and are best known for having found the world’s largest chariot battle against the Egyptians after which they signed the world’s first ever peace treaty (Mark, 2011). Garstang’s work helped to give an insight to the once powerful civilization and many of the artifacts that he discovered are still on display at Liverpool University (Garstang, 1929).

After Garstang served in the First World War with the Red Cross in France, he was appointed to be in charge of the newly founded School of Archaeology in Jerusalem (1919-1926). He also became the founding Director of the British Mandatory Department of Antiquities of Palestine that same year, a post he held until 1926 where he found the time to explore the country for archaeological findings. In Palestine, he made many notable discoveries such as the site of Hazor. He also did significant research on the topography of the area. However, his most important archaeological work in Palestine and perhaps what he is known for the most was his excavation of Jericho.

Jericho

Jericho is considered one of the oldest cities in the world. Located in the plain of Jordan, six miles north of the Dead Sea. In it’s prime Jericho was a mighty fenced in city amidst a great grove of palm trees. It is also known as “The Date City” or “The City of Palm Trees” because of its beautiful green oasis and distinct fragrance. Dating back almost 10,000 years, Jericho is thought to be the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world. Because of its abundance of fresh water in such a desolate area, Jericho made a perfect environment for a flourishing trade destination. At its height, Jericho was known as the most important city in the Jordan valley and it was the strongest fortress in Canaan due to the walls that surrounded it. Jericho is especially famous for being conquered by Joshua and the Israelites who were being led by God through the wilderness from Egypt. The city was built on top of a nearly 70 foot tall mound. Often times, people wouldn’t tear down an old city; they would simply build a new one right on top of it. New walls were even built on top of the existing walls in the tell of Jericho. In the scripture, there is account of the Israelites defeating the city when they came into the promised land after wandering the wilderness for 40 years. In the book of Joshua it is said that God gave Jericho “into their hands”, and the city was “accursed” therefore all of the inhabitants of the city and its products were to be demolished. Only the precious metals (gold, silver, brass, and iron) were saved. The Israelites were said to have marched around the city for 7 days straight, until the final day the priests blew their trumpets and the great walls surrounding the city just fell. They then stormed the city and set it afire. Only one woman, a prostitute that helped the Israelites spy, survived the attack. (Bartlett, 1983)).

Garstang was not the only archaeologist to explore the ruins left behind at Jericho. Captain Warren of the British archaeological society began the first excavation as long ago as 1867. He discovered a shaft that was nearly 20 feet deep that contained some charred timber. At the time, archaeological technique was still very primitive so he didn’t think much of the shaft, however expeditions after his determined that the shaft was in fact part of the wall that protected the great city.

In 1930, Garstang led a team to Israel with the hope that they could shed some new light on the ruins of Jericho. This excavation lasted until 1936, and turned up many new findings. They were able to dig all the way down into the Neolithic period, when settlement at Jericho first occurred. They were able to find four successive incarnations of the great city. Garstang focused mainly on the fourth city that was said to be destroyed by Joshua and the Israelites. The team was able to find many artifacts ranging from grain stores to figurines of animals. In the process of digging through the ruins, he discovered four distinct layers that were separated by bands of burnt material. Indicating that the city was leveled by fire or natural disaster such as an earthquake, and then a new city was built directly on top of its predecessor. As per usual with archaeology, pottery was the most abundantly found artifact at the site of Jericho. Usually, pottery found at a site could be compared with other pottery from the region to provide absolute dating. However the pottery that Garstang and his team unearthed was unique in the way that it bore no resemblance to any other forms of pottery found at other sites in the area. Jericho’s pottery had its own distinct style. The earliest artifacts to be found were blades and arrowheads made from flint that was dated back to around 5000 BCE. From this Garstang concluded that Jericho housed developed, domesticated life from the very beginning of its creation. He also discovered the ruins of a great building, which seemed to have been rebuilt in each reincarnation of the city. From this he surmised that the building was of great importance and from that he predicted it was a sort of religious temple. Garstang also located the ruins of what he believed to be a palace, built in each of the four cities on the highest ground within the city walls. Another interesting find was a necropolis located 250 yards to the west of the city mound. The tombs there were either small chambers or shallow, round graves. Each tomb contained pottery and other offerings that was used to date the necropolis’ use from the third millennium BCE until the city’s fall in 1400 BCE.

Garstang’s main interest in excavating Jericho was the walls surrounding it. He hoped that he would find significant information in order to support the biblical account of the Israelites conquest of the city. He was able to find the walls of all four cities. The first wall, enclosed about four acres of ground and was dated back to 3,000 BCE. The second wall, dated at 2,500 BCE followed much of the same plan as the first wall it just had added thickness. The third wall was considerably larger, enclosing about nine acres and dating back to 1,800 BCE. The fourth and final wall was incredibly eroded but its shape followed that of the first two walls, this was the wall that Garstang was the most interested in because it would be the one toppled by Joshua and the Israelites.

This fourth wall was doubly enclosed. The outer wall was six feet thick and the inner wall was twelve feet thick and considerably taller. These walls were constructed of unbaked mud bricks, and therefore were not very sturdy. Garstang found the wall to have mostly collapsed, and it was burnt extensively along with all of the houses unearthed in the top layer. He surmised that an earthquake caused this massive destruction, which would fit into the story line of the scriptures written by Joshua. Jericho lies on a major fault line that runs across the west side of the Jordan valley. The walls of the fourth city had all fallen outwards, which would have been the outcome of an earthquake. And the city’s houses were leveled in a way that humans that that time couldn’t have managed (Garstang, 1948) .

In his book, The Story of Jericho, Garstang allows the reader to determine for himself what affect his discoveries should have on the biblical account of the fall of Jericho. However, Garstang himself was a devout Christian and he often looked to archaeology to validate his beliefs. He chose to believe that an earthquake was God’s will provided to aid the Israelites in the capture of the city while many others just see it as a simple natural disaster. His bias is evident in many of his accounts of the excavation. Whenever he found ruined walls or evidence of fire he immediately linked them to the story of Joshua without any thought to other causes. Garstang’s findings certainly could be evidence of the truth in the scriptures, but he failed to present any other options.

Major Contributions to Archaeology

Garstang’s life was full of academic achievements. In 1902, he was appointed as the honorary reader in Egyptian Archaeology at Liverpool University. This position gave him the opportunity to raise funds in order to create an institute of archaeology in 1904. He was honorary secretary for the institute for 40 years and it was eventually incorporated into the university itself. In 1907, Garstang was appointed a professorship in the new division of methods and practice in archaeology at Liverpool University, a position that he held until 1941. While at an excavation in Turkey, he came up with the idea of a British Institute of archaeology at Ankara, and in 1948 the institute was opened. Garstang was appointed the first director, however he retired the following year to accept the position of the presidency of the institute. He was appointed a chevalier of the Légion d'honneur (1920), received the honorary degree of LLD from Aberdeen (1931), and was made a corresponding member of the Institut de France (1947), and CBE (1949).

Garstang published many writings on his works. His time in Asia Minor studying the Hittites prompted a very valuable topographical study of the Hittite monuments in 1910 titled, The Land of the Hittites. His work in this area virtually helped to rediscover the forgotten but once great civilization of the Hittites, and many of the artifacts that were discovered under his leadership can still be seen in his archives at Liverpool today. During his time as a professor at Liverpool University, Garstang published a journal titled, The Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology which students were able to learn from for many years to come. His work on the topography of Palestine resulted in the publication of Joshua Judges (1931) and The Heritage of Solomon (1934). He also published a book on his work in Jericho called The Story of Jericho, in which he published his findings and left interpretation up to the reader.

Legacy

Garstang’s final excavation was at the site of Mersin, where he discovered important remains from both the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age. Two days before his death, his last wish was to revisit this site. On a cruise at the time, the boat came ashore to grant his wishes. Garstang passed away on the cruise ship on September 12, 1956 (Gurney, 2004) .

Garstang’s work on the Hittites allowed a forgotten civilization to be re-found, and his work in Jericho helped to solidify the faith that many Christians have in the scriptures. Past his work in the field, Garstang aided in the founding of several different institutes of archaeology and therefore helped produce a scholarly environment for archaeologists to study in in many different areas of the world for generations to come.

Citations

Alchetron. "John Garstang." 2016. Web. 14 Apr, 2016.

O. R. Gurney, ‘Garstang, John (1876–1956)’, rev. P. W. M. Freeman, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; May 2012 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/33341. 14 Apr, 2016]

The British Museum, John Garstang and the Discovery of the Hittite World, Liverpool. The British Museum. Web. 1 May 2016.

A. H. Sayce, Reminiscences (1923) · J. Shore, unpublished history of the School of Archaeology, Classics and Oriental Studies, University of Liverpool, 1985, University of Liverpool, School of Archaeology, Classics and Oriental Studies [typescript] · personal knowledge (1971)

Mark, Joshua J. "The Hittites." Ancient History Encyclopedia. N.p., 28 Apr. 2011. Web. [http://www.ancient.eu/hittite/]. 1 May 2016.

Garstang, John. The story of Jericho. Marshall, Morgan & Scott, 1948.

Bartlett, John Raymond. Jericho. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1983.

Garstang, John. "The Hittite Empire." (1929): 894-898.

Garstang, John. The Burial Customs of Ancient Egypt as illustrated by tombs of the Middle Kingdom. A Constable & Company, Limited, 1907.

Abraham. Ruiny pałacu z VIII w. w Khirbet al-Mafjar w Jerychu (Autonomia Palestyńska). Zdjęcie wykonał A. Sobkowski dn. 9 March 2006. Web. 1 May, 2016.