Lady Aileen Fox

Jillian Stoneburg

Early Life/Biography

Lady Aileen Fox was born Aileen Mary Henderson on July 29, 1907 (Goldman). She was born to a comfortable middle class family in London, England (Allan). Her father was a solicitor and her mother stayed at home (Goldman). She spent much of her childhood in London and Surrey. She had a well ordered household and childhood. Her house was always full relatives and her mother was always entertaining. She was raised to be proper from dance lessons and was not allowed to use toy that were considered dangerous such as scooters (Fox). She had lacked the attention of her mother, but had a nanny who mainly took care of her throughout her early years. She had two younger sisters, Shelia and Mari (Fox). World War I had little effect on her and her family as her father had a wasted leg and shrunken foot from poliomyelitis as a child and was unfit for war (Fox). In 1919, her family moved to Surrey permanently and she personally noted that this marked the end of her childhood (Fox). Her mother wanted her to be a proper lady and marry into a well off family. Aileen did not see herself in a sedentary lifestyle and wanted to be as well educated as she could and to challenge herself as much as possible. As a young girl she attended several schools and was very well educated. These schools included Downe House School in Berkshire, Chinthurst, and Rene’s (Fox). She also supplemented her schooling with reading on her own. She convinced her mother to let her attend Cambridge after she agreed to be presented as a debutante at court in 1926 (Soffe). Early interest in archaeology was sparked by continental travels with her father when she was young. Aileen married Cryril Fred Fox in July 1933 (Quinnell). He was the director of the National Museum of Wales and was knighted in 1935 for his work in the museum. Together they had three sons, Charles, Derek and George (Quinnell).

Archaeology Career

She read English at Newnham College, Cambridge from 1926 to 1929; however, she did not receive her full degree until 1948 because she was a woman (Soffe). After she completed her schooling she worked at the Roman fort in Richborough at Kent. She had no formal archaeology training when she began because in the 1930s since it was not required in Britain (Goldman). Her excavations from Richborough lead her to help set up and run a site museum (Soffe). As she continued her work, she became better known in a rising generation of archaeologists. After she married her husband, she collaborated on the fieldwork he was conducting in South Wales, which later led to her to work on her own projects. During this time one of her most notable excavations was the Caerleon Roman fortress (Goldman). Here she excavated an amphitheater and other parts of the fortress. Her most exciting discovery in the fortress was one in which with the backing of the museum and a work force Fox completed one her own. She found a hoard of first century gold coins under the floor of timber barracks (Soffe). In order to find this, she strategically had excavation trenches across what she knew to be barrack blocks and centurions’ quarters (Soffe). This work as well as her work in Richborough drove her interest in the Roman occupation of Britain. During World War II, she lectured in archaeology at University College in Cardiff. Following the war, Lady Aileen Fox took on the project of rescue excavation on the bombed site of the Roman city of Exeter (Quinnell). This was considered to be the major project for her during her life and where she directed three seasons of excavations (Goldman). Exeter had been damaged during the war and had been essentially already dug up and was in ruins from Germany bombing. According to Dr. Nash-Williams, the archaeologist she worked with at the Caerleon Roman fortress, all the archaeology in Exeter could be understood with a few placed trenches (Soffe). This is exactly what the war left Fox with; however, she went well beyond just a few trenches in the area. Exeter was a minor western trading post with very little military significance in the Roman conquest of Britain and there was very little Romanization present in the town (Comfort). Although Fox was only supposed to be there for three seasons; however excavations in this area continued into the 1960s. In 1964, Fox found the first evidence of Roman military presence in Exeter (Soffe). After her husband’s retirement, she became a senior lecturer at Exeter University from 1948 to 1972 (Quinnell). During the time she spent in Exeter, Fox went on several research excavations in south west England. Two of her most important were Dartmoor, at Kes Tor and Dean Moor (Soffe). These two locations provided much insight to prehistoric settlements in Dartmoor. In this location, Fox found a series of distinct hillforts. Before her work there was little evidence of Roman military in south west England, but these hillforts indicated that there was a probable auxiliary fort at North Tawton which is the northern edge of Dartmoor along with other fortlets in the area. She also conducted four seasons of excavations between 1965 and 1969 alongside William Ravenhill at Nanstallon in Cornwall (Soffe). At this location, they were able to find clear evidence of a Roman fort. The fort at Nanstallon was a small fort that only had one main period of occupation between 55 and 65 AD (Soffe). This could be linked back to the broad military period in south west England that was being uncovered in Exeter. Fox believed it to be a mix of cavalry and infantry and was then decommissioned (Soffe). She also did excavations in Devon at Bantham. Here she found evidence of Roman culture outside of what was originally considered to be the Roman period (Soffe). Aileen Fox’s time at Exeter led her to many excavations and research into the Roman occupations of England. Much of her research continues to spark interest in the archaeological community today.

Major Contributions to the Field of Archaeology

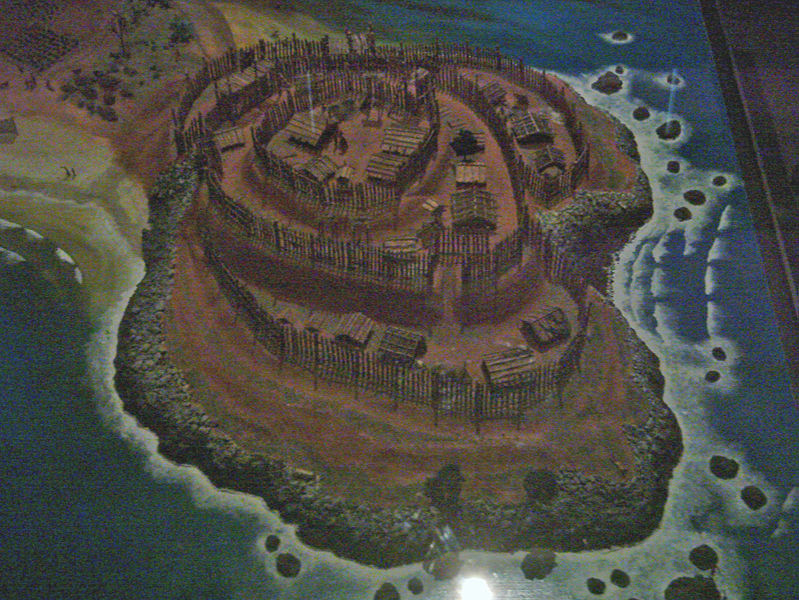

She is considered to be one of the founders of modern archaeology in south-western England. She pioneered several modern archaeological techniques in the process of excavating Exeter. She did not use the traditional layout of the “Wheeler method” of gridded squares, but instead went with trenches and open areas (Soffe). She used this method because much of the site was already pre-exposed from bombings during World War II. This set the pattern for later practices in British excavations (Soffe). Also Exeter was one of the first rescue projects of its kind (Soffe). Her work led other archaeologists to lead rescue excavation in England in war damaged areas although rescue archaeology really did not become popular until the 1970s (Soffe). Outside of her excavation work she contributed quite a bit to the archaeology community and its growth. When Lady Aileen Fox first started her archaeology career, there was very little to the community of archaeologists. Since she a women who did not abide by the typical gender roles of the time, she was able to expand her archaeological career as well as the archaeological community in south west England and in Auckland, New Zealand. Outside of her lectures and excavations, she had several publications on her work. Most of these publications outlined her work in Exeter and on the Maori Pas. Of her publications her most well-known ones are Roman Exeter: Excavation in War-Damaged Areas 1945-7, Transactions of the Devonshire Association, South West England, Prehistoric Maori Fortifications, and Carved Maori Burial Chests (Allan). These publications helped her to establish herself and move forward in her career. She found that the archaeology community in south west England needed to grow and expand. She helped to archaeology as a larger form of study in these two areas of the world. She was the vice president for the Council of British Archaeology. Within this group, she was responsible for setting up local Group XIII (Soffe). This group helps to involve and promote archaeology to those without archaeology experience (Allan). She also helped to reestablish Devon Archaeological Society ("About Us").

Legacy

Although Lady Aileen Fox died on November 21, 2005, she will not soon be forgotten for all of her work and contributions to the archaeology community. Not only was she able to overcome the typical role of female in society during that time, but she also made a major impact on the archaeology community in Southwest England and in New Zealand. Outside of her pioneering methods of open area and trench excavations, Lady Fox encouraged the growth of archaeology learning everywhere she went. She helped to expand the archaeology department in Exeter as well as develop many positions in which her successors held after her retirement. She inspired many of her students to pursue careers in archaeology even in her later years. Lady Aileen Fox wanted to people to understand the importance of archaeology and those who are involved in uncovering the material culture. She is often considered one of the last archaeological members of who shaped the modern discipline and the founder of modern archaeology in south west England. She also helped to establish the archaeology department at Exeter University which became its own department in 1998 (Soffe). Her work in the archaeological community had great significance in the establishment and development of modern archaeology both in southwest England and New Zealand. She also had a major influence in the studying the Iron Age and Roman worlds.

References

"About Us." Council for British Archaeology. Council for British Archaeology, 2012. Web. 13 Apr. 2016. http://new.archaeologyuk.org/about-us/.

Allan, John. "Aileen Fox." The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media, 15 Dec. 2005. Web. 20 Apr. 2016. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/aileen-fox-519642.html.

Biddulph, Kim. "Lady Aileen Fox." TrowelBlazers. Trowelblazers, 2014. Web. 15 Apr. 2016.http://trowelblazers.com/lady-aileen-fox/.

Comfort, Howard, and Aileen Fox. "Roman Exeter (Isca Dumniorum): Excavations in the War-Damaged Areas, 1945-1947." The Classical Weekly 47.2 (1953): 28. Web.

Fox, Aileen. Aileen: A Pioneering Archaeologist. Leominster, Herefordshire: Gracewing, 2000.

"Fox Aileen." Archaeopedia. N.p., n.d. Web. 5 Apr. 2016. http://archaeopedia.com/wiki/index.php?title=Fox_Aileen.

Goldman, Lawrence. "Aileen Mary Fox." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford U, 2013. 398-400. Print.

Kirch, Patrick Vinton. The Evolution of the Polynesian Chiefdoms. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1984. Print.

"Pā." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 29 Apr. 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/P%C4%81

."The Pa", from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H. McLintock, originally published in 1966.Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 22-Apr-09. http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/1966/maori-material-culture/page-10.

Quinnell, Henrietta. "Obituary: Aileen Fox." The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 19 Jan. 2006. Web. 6 Apr. 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/jan/20/guardianobituaries.obituaries.

Soffe, Grahame. "Aileen Fox and Her Contribution to Romano-British Archaeology." The Association for Roman Archaeology 18 (Nov. 2005): 22-25. Print.

"Tiromoana Pa." Heritage New Zealand. HERITAGE NEW ZEALAND, n.d. Web. 16 Apr. 2016. http://www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/details/6506.