Arthur Evans

Emily Paul

Biography

Arthur Evans was born on July 8, 1851 in Nash Mills, England. He was the first child of John Evans and Harriet Dickinson. Arthur's father, John Evans, had worked in his Uncle's paper mill where he met and married his cousin, Harriet in 1850. The couple had 4 more children, Philip, Lewis, Harriet, and Alice, before Harriet's own death in 1858 (Ashmolean) . Despite his mother's early death, his father lived a long life until 1908. John Evans's salary from working in the paper mill helped fund Arthur's future career as an archaeologist. Not only did his father's salary help fund his future career, but his father's work at the mill also helped inspire it. His father had been studying water resources around the mill and during the process discovered Stone-Age artifacts. As Arthur grew older, John brought Arthur along to help look for more artifacts along the stream beds. After this, John became an antiquary and published many books about his discoveries. John's connections from his publications helped Arthur begin his archaeological career.

Arthur Evans came from a family where the men were well-educated. Arthur started his education early at Callipers Preparatory School as a child. He then advanced to Harrow School in 1865 at the age of 14, where he became a co-editor of The Harrovian, the school newspaper. In 1870, after graduating from the Harrow School, he enrolled and attended Brasenose College, one of the colleges of the University of Oxford (Historians). There he studied modern history, although he was mostly interested in archaeology. While he was a studious man, he had difficulty graduating due to failing one of his exams. Despite this, his connections with the examiner allowed him to pass and graduate in 1874, at the age of 24.

During his years at Oxford, Arthur went on a series of adventures. In 1871, he visited Hallstatt, Austria where his father had excavated previously. After collecting some artifacts for his personal collection there, he then traveled to France. In France, he visited Paris and then Amiens, where he hunted for Stone-Age artifacts in gravel quarries. In 1872, he then traveled into Ottoman territory by the Carpathian Mountains. Then in 1873, he traveled to Finland and Sweden. It is here that he began to delve more into his archaeological roots. He took many notes and drawings of people and artifacts in this region. When Arthur went back to England for his Christmas holiday, he helped John Gardner Wilkinson, a well-known British Egyptology archaeologist, catalogue a coin collection, when he was unwell. It was soon after he graduated that he applied for the Archaeological Traveling Studentship offered by Oxford, but two people within the university who did not like his work, turned him down. Instead, he was sent to Gottingen, Germany to research modern history. He did not enjoy either the topic nor his living situation while he was there, so he abruptly left for another adventure to the Balkan Peninsula. This proved to be the end of Arthur Evans formal education as he was an adventourous man who would rather be out in the field rather than reading books.

Archaeology Career

Arthur Evans archaeological career had no concrete beginning or end. Even during his childhood, he was helping his father discover artifacts. However, we will consider the beginning of his formal career to be after he graduated from the University of Oxford.The beginning of his formal career did not start as archaeology at all, but journalism. His brother Lewis and him traveled to Bosnia in 1875 where they felt sympathy for the oppressed people in the Balkan Peninsula and also in Crete. Arthur's liberal ideas about the sensitive situation caused him to be put in a cell for a brief amount of time. Once released, he wrote about his experiences and was hired in 1877 by the Manchester Guardian to report on events in the Balkans. To continue his career, he traveled back to Bosnia and began collecting portable artifacts, usually sealstones. While he was there, he joined back up with the man that helped him after being released from prison named Edward Freeman. As they became friends, Arthur fell in love

Once the family was back in England, they rented a house near Oxford in 1883. During this period, Arthur Evans experienced a period of unemployment, but used this time to finish his Balkan studies. After that, him and Margaret traveled to Greece where they met with Heinrich Schliemann where they examined Mycenaean artifacts. It was this even that began his formal archeaological career that he would become known for. Soon after, in 1884, he was offered a position as the keeper of the Ashmolean Museum. The museum was going through a hard time as it had lost a large portion of its historical collections to another museum. With Arthur's help, the museum was revived and turned into an archaeological museum.

In 1886, his archaeological roots once again called to him. A cemetary in Aylesford, England was discovered as being dated around the British Iron Age. Evans did some coin, metalwork, and pottery analysis to the artifacts found in that area to date the cemetary (Hingley) . After doing some work there and publishing some articles, Arthur continued his life traveling, revitalizing the Ashmolean museum, and continuing his archaeological work. In 1892-1893, Arhur's way of life drastically changed. His good friend and father of his wife, Edward Freeman, passed away due a combination of poor health and smallpox. As him and Margaret mourned Edward's loss, she too fell ill. In an effort to save her, Arthur bought some land in Boar's Hill, near Oxford, where he began to build a log cabin elevated off the ground in an attempt to keep her away from cold, damp conditions. They took a brief vacation after beginning construction by visiting Athens to meet John Myres and dsicuss some seal stones that were covered in strange writing from Crete. On their travels, Margaret was stricken by her disease and despite Arthur's efforts to save her, in 1893, she too passed away due to what is speculated to be tuberculosis or a heart attack. She was 45 when she passed away. Arthur, with the loss of his wife and good friend, went into a period of grieving. It is during this time that he took a break from his archaeological career and instead focused his energy into completing the mansion on Boar's Hill, which he then named Youlbury.

For about a year, Arthur Evans archaeological career had paused and didn't start rolling again until tension began to increase on the island of Crete. It is this tension that attracted Arthur's interest due to the well-known site of Knossos being located there. The connection between Knossos, his engraved stones and jewelry, and the Cretian language, got him out of his grieving spell and back into the hang of things. He joined a group to watch the developments of Knossos as the Ottoman government decided the site's fate. The site soon was given to a native Cretian owner for safe-keeping, as the owners were told to keep the price of the site high so no one would buy or excavate it. Many archaeologists gave up due to the price and left Crete. However, Arthur Evans, the clever man he was, found his way around the problem. He knew that individuals themselves did not have the funds to pay for the site nor would the owner accept money from one person, so Arthur created the Cretan Exploration Fund. He knew the owners would sell to a fund, as it meant there would be no singular ownership. However, Arthur used the funds as a cover, as he did not share that he was the single and only contributor to the site. In 1899, Evans used money from a family inheritance to buy the site at Knossos (Athena) . As the tension decreased in Crete, many archaeologists flooded back in to obtain permits to excavate Knossos. However, they soon discovered what Arthur had done and were not able to get permits. Arthur hired 32 personal diggers and began work at Knossos in 1900. Within a few months, most of the palace was uncovered and many artifacts were discovered. In 1905, the excavation was completed. Knossos was his most famous excavation and he spent the rest of his career publishing articles, books, and theories on his discoveries there.

Major Contributions to the Field of Archaeology

Most of Arthur Evans' contributions to archaeology were from his discoveries at the site of Knossos. However, he did contribute in other parts of the field also. One of those contributions would be the Ashmolean Museum. During his time there, he managed to not only revive the museum from near closure, but also helped it flourish. He transformed the history museum solely into an archaeology museum. Arthur managed to receive some of the collections back that were taken from its premises and also made major contributions himself. He donated all of his father's archaeological collections to the museum along with his own extensive collections, including his artifacts that he collected from Knossos. Presently, the museum has one of the best display of Crete artifacts outside of the island itself, due to Arthur Evans generous contributions.

Arthur Evans also contributed to British Iron Age studies. This development came out soon after Evans excavated the cemetary in 1886. Arthur made the connection between this Aylesford site and the Swarling site and developed theories on the culture. Not only did he discover the first wheel-made pottery in Britain here, but he conlcuded the site belonged to a culture similar to the continental Belgae, that dates around 75BC. Many people of the field still view his work as a great contribution to the Iron Age studies.

And finally, Knossos. This Cretian site is what Arthur Evans is most notably known for excavating and studying. Knossos is known for being "the largest Bronze Age settlement on the island of Crete" (Hogan). It was an expansive palace made up of over 1,000 interlocking rooms.

Legacy

Arthur Evans' legacy was remembered in several different way after his death. He left behind many of his honors at the societies he had joined, including the Lyell Medal, the Copley Medal, an honorary doctorate from the Univeristy of Dublin, and being knighted by King George V for his contributions to archaeology. He also transformed the Ashmolean into an archaeological museum of international important and a first-rate research instituation (Oxford). The Ashmolean museum still holds the largest collection of artifacts outside of Greece after his generous donations. He donated money to a studentship, to continue the discovery of archaeolgoy. While the mansion on Boar's Hill has since been demolished, part of the estate was given to the Boy Scouts and Youlbury camp, to be available for their use. Also, in Arthur and Margaret's honor, a garden was erected for their legacy. In the end, "we cannot but admire the man who not only discovered the Minoans, but who also demonstrated as never before how archeology can reconstruct the past" (Selkirk) .

References

Image 1. "Arthur Evans" Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 13 June 2014. Web. 14 April 2016.

Image 2. Casey, Sarah. "Ashmolean Museum Oxford Forecourt". 2014. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, United Kingdom. Wikipedia Commons. Web. 06 May 2016.

Image 3. Gagnon, Bernard. "The North Portico in Knossos, Crete, Greece." 2011. Knossos, Crete, Greece. Wikipedia Commons. Web. 06 May 2016.

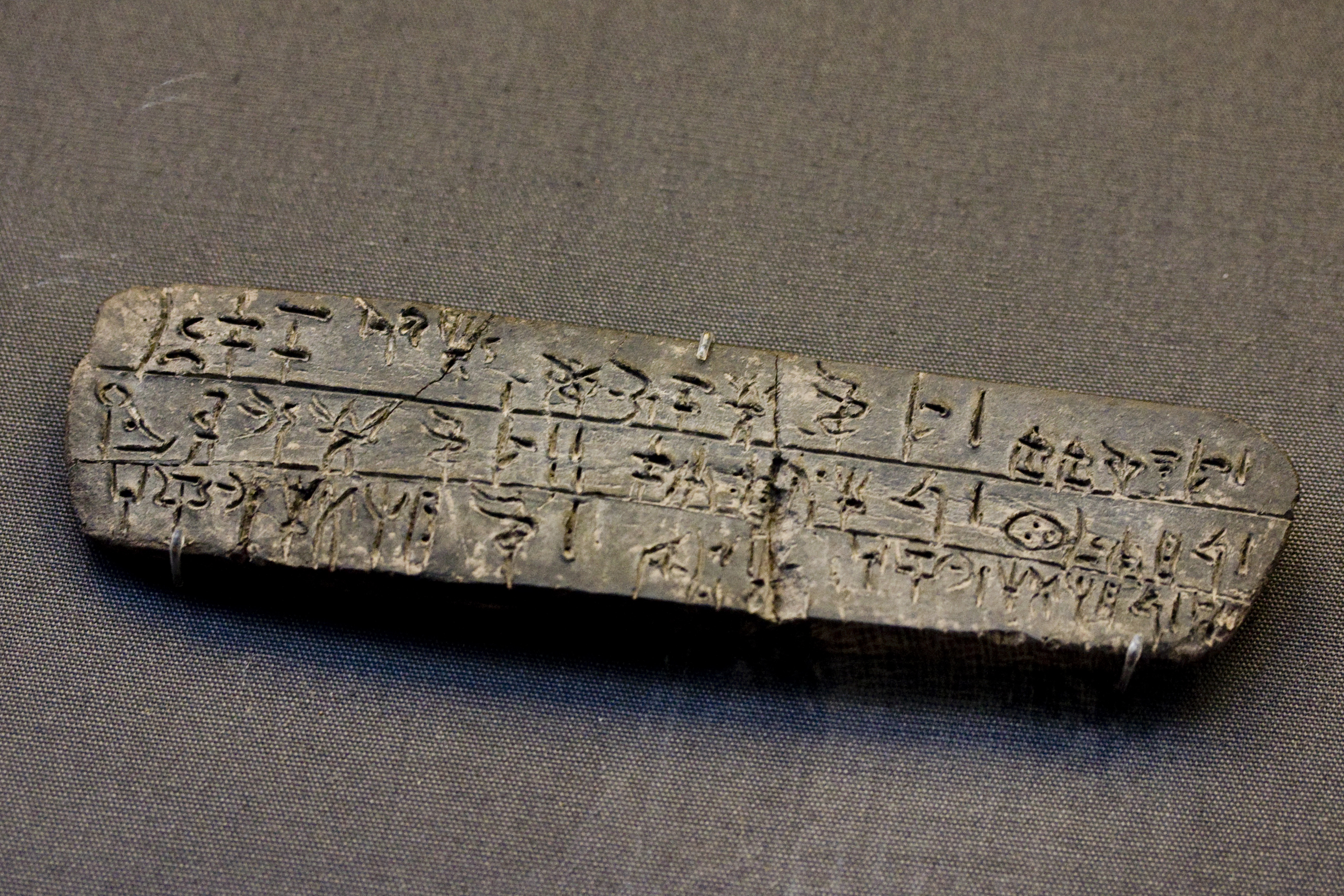

Image 3. Wuyts, Ann. "Clay Tablet Inscribed with Linear B Script. 2010. British Museum, London. Flickr. Web. 06 May 2016. Hogan, Michael. "Knossos (Ancient Village, Settlement, Misc. Earthwork)." The Modern Antiquarian. Julian Cope, 14 Apr. 2008. Web. 06 May 2016. Selkirk, Andrew. "Sir Arthur Evans - Barbarism and Civilization." WordPress, 25 Jan. 2012. Web. 06 May 2016. Athena Review. "3.3 Minoan Crete: Sir Arthur Evans and the Excavation of the Palace at Knossos." AthenaPub. Athena Publications, 2003. Web. 06 May 2016. "Sir Arthur Evans: Biography." The Sir Arthur Evans Archive. University of Oxford, 2012. Web. 06 May 2016.

"Sir Arthur Evans (1851-1941)". Sir John Evans Centenary Project. The Ashmolean, 2009. Web. 06 May 2016.

Hingley, Richard. "The Recovery of Roman Briatain: 1586-1906: A Colony so Fertile." Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print. Page 300.

"Sir Arthur J. Evans." Dictionary of Art Historians. Web. 06 May 2016.