Lewis Binford

Tom DiPonio

Introduction

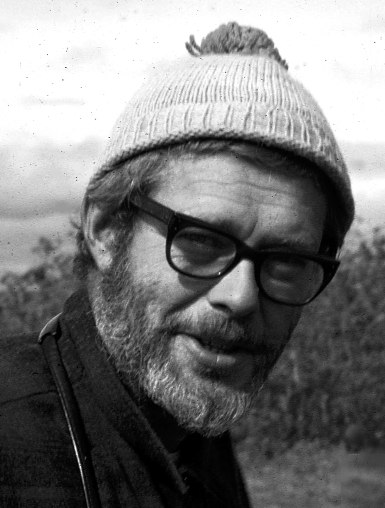

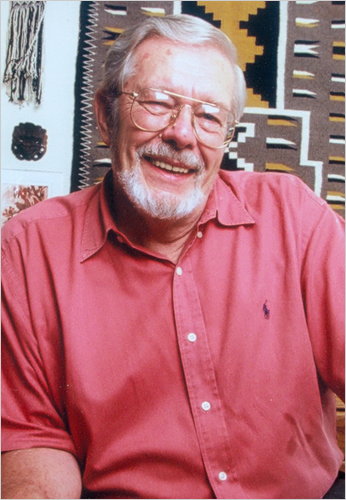

Lewis Binford was born and raised in Norfolk, Virginia. Binford was not a very good student in high school, but afterwards, when he studied wildlife biology at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute, he excelled greatly. Before deciding to pursue a biology career, Binford was drafted into the military for World War II. Here he was assigned with a group of anthropologists whose job was to help resettle the people on the Pacific Islands under U.S. Control. He also was part of the group that recovered lost archaeological material from the tombs in Okinawa with no training in excavation whatsoever. His time in the military is what really sparked his interest in archaeology and anthropology. After his years in the military, Binford went the the University of North Carolina where he studied anthropology. During his time here, he started his own contracting business to help pay for his education. After Gaining a BA from UNC, he then went to the University of Michigan to get his MA and PhD. After his graduation, he served on the faculties of the University of Chicago, the University of California at Santa Barbara and the University of California at Los Angeles before he became a professor at the University of New Mexico. He remained here for another 23 years until finally, he joined the Southern Methodist University faculty in 1991 for 12 years, to then retire in 2003 (SMU). During his life, Lewis Binford was married a total of 6 times but he only had 2 children, only to lose his only son in a tragic car accident. He had both children with his first wife Jean Riley Mock. His third wife Sally Binford was also an archaeologist, and the two married while they were graduate students. During their time together, they had written the book "New Perspectives in Archaeology". At the time of his death he was married to Amber Johnson who was once one of his students at Southern Methodist University.

Early life/Biography

Lewis Binford was born and raised in Norfolk, Virginia. Binford was not a very good student in high school, but afterwards, when he studied wildlife biology at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute, he excelled greatly. Before deciding to pursue a biology career, Binford was drafted into the military for World War II. Here he was assigned with a group of anthropologists whose job was to help resettle the people on the Pacific Islands under U.S. Control. He also was part of the group that recovered lost archaeological material from the tombs in Okinawa with no training in excavation whatsoever. His time in the military is what really sparked his interest in archaeology and anthropology.

After his years in the military, Binford went the the University of North Carolina where he studied anthropology. During his time here, he started his own contracting business to help pay for his education. After Gaining a BA from UNC, he then went to the University of Michigan to get his MA and PhD. After his graduation, Binford became a professor at the University of New Mexico after a 23 year teaching career here, he joined the Southern Methodist University faculty in 1991 for 12 years, to then retire in 2003.

During his life, Lewis Binford was married a total of 6 times but he only had 2 children, only to lose his only son in a tragic car accident. He had both children with his first wife Jean Riley Mock. His third wife Sally Binford was also an archaeologist, and the two married while they were graduate students. During their time together, they had written the book "New Perspectives in Archaeology". At the time of his death he was married to Amber Johnson who was once one of his students at Southern Methodist University.

Archaeological career

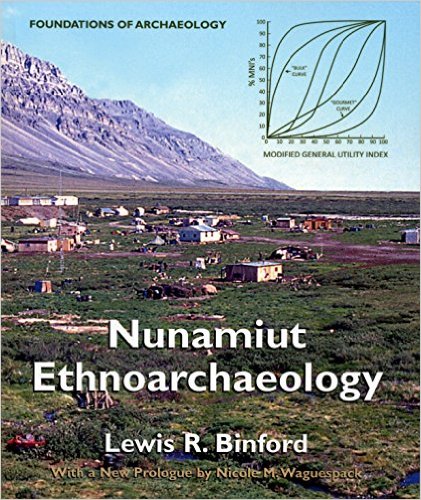

Never did Lewis Binford dig up any great artifacts, or find famous historical sites but in the field, Binford performed excavations in various countries including North America, Africa, Europe, and the Middle East. His biggest contributions came in the study of prehistoric stone tools and their relation to early human activity. He also made contributions in the area of Alaskan Eskimo people. Binford wrote a multitude of books and articles, some of his most popular include but are not limited to: “Nunamiut Ethnoarchaeology”, “Bones: Ancient Men and Modern Myths”, “In Pursuit of the Past”, “Constructing Frames of Reference: An Analytical Method for Archaeological Theory Building Using Ethnographic and Environmental Data Sets”, and “Debating archaeology”. He also wrote one by the name of “hunting and gathering book” which was densely filled with charts graph and text. It includes “11 problems, 86 propositions, and 126 generalizations”(Lekson). He is said to have wrote twenty books and over 150 articles in his day. “These books are also a handy roadmap to changes in his thinking over time. Binford’s influence spanned nearly five decades, though that influence diminished over time, particularly in his last two decades as others, building on or reacting to the foundation he had helped create, took archaeological theory and practice in different directions” (Meltzer).

Binford's research expanded throughout the world from Alaska and Australia. Much of his focus was spent on the area of hunting and gathering. He spent 20 years in areas of Africa, Alaska, and Australia doing research on the patterns and day to day lives of these ancient hunter gatherer societies. He performed what is known as ethnoarchaeology-“ Ethnoarchaeology is the ethnographic study of peoples for archaeological reasons, usually through the study of the material remains of a society. Ethnoarchaeology aids archaeologists in reconstructing ancient lifeways by studying the material and non-material traditions of modern societies. Ethnoarchaeology also aids in the understanding of the way an object was made and the purpose of what it is being used for” (Wikipedia).

“During the 1960s he famously clashed with the venerable French archaeologist, François Bordes, over the interpretation of a “Mousterian” (after a site at Le Moustier, in the Dordogne) assemblage of stone tools dating from a glacial period around 40,000BC” (The Telegraph).. Bordes claimed that this site did not reveal a random mix of tools but instead fell into four categories known as Mousterian Variants. He said that these tools provided evidence for different groups of roaming Neanderthals. Binford however concluded that the difference in the tools was a result of different activities being performed at each area. He made the argument that some of the sites may have been location where people lived while other may have been areas of work. To find the evidence for his conclusion, Binford traveled to Alaska and spent time living with the group known as the Nunamiat. These people had very similar living conditions to those that lived in the time the stone tools were originally from. Though this debate was never truly settled or considered right or wrong, Binford’s way of research had a profound impact on the way archaeological practice was done.

In 1968 is when Binford New Archaeology really showed its success in “New Perspectives of Archaeology”. Even with its success, Binford was still much dissatisfied. This is when he decided to completely change his course by immersing himself in the contemporary culture. He wanted to learn what was made, why it was made, and what the findings would be for archaeologist. This is when he wrote Nunamiut Ethnoarchaeolgy in 1978 which explains his field studies in northern Alaska studying the caribou hunters. He followed this up with a series of papers discussing how the hunters made decisions in the seasonal contexts and different harsh landscapes. He also revolutionized the study of animal bones in relation to past behavior. The lessons he found here were further expanded through his studies in Australia and Africa. His book Bones: Ancient Men and Modern Myths (1981) used this evidence to study the lifestyle of our ancient ancestors. He clashed with the previous idea that man was the great hunter who dominated the land, saying man was mostly scavengers. “With his fifth wife, Nancy Medaris Stone, Binford then set out on a global survey of the evidence for our earliest ancestors travelling to China, India, Africa, South America and across Europe. In China in the mid-1980s, they caused a furor by applying the concept of Homo erectus the scavenger to the "Peking Man" site, the Zhoukoudian cave system near Beijing” (Gamble). Along with some graduate students from the University of New Mexico, they worked on a global survey of hunters and gatherers. This research reached its climax in 2001 with the book “Constructing Frames of Reference”. After this, Binford finally returned to his question of why humans turned to agriculture. Contrary to popular belief, Binford believed that the farmers back then were actually the failures of the time rather than the great successes. “By constructing a detailed demographic argument supported by ecological data, he showed how mobility, the eternal human adaptation, became compromised – and our future sealed. Among the research students who contributed to this enterprise was Amber Johnson, who became his sixth wife and co-researcher” (Gamble).

Major Contributions to the Field of Archaeology

Most people remember Lewis Binford for his contributions in archaeological theory and his ethnoarchaeological research. In the 1960’s, he was also the leader of the New archaeology movement which became known as processual archaeology. He basically changed the way archaeology was done forever. He said that there can be no limit to the questions asked about the past. He wanted not only archaeologist, but everyone to expand their horizons on the past. He didn’t want an artifact to be just that, an artifact. He wanted these objects and their sites to be a portal into the past culture. He wanted for people to be able to dig into and look into the past through the object of interest and discover why, how, and who used it. “Professor Binford brought about a virtual revolution in archaeology in the 1960s and 1970s by elevating its status from a descriptive study of antiquities to a scientific discipline devoted to anthropological understanding of ways of life of ancient societies. His ‘archaeology as anthropology' proposition emerged as a dominant paradigm in contemporary archaeology” (Rajendran). This New archaeology is mainly focused on cultural evolutionism, and understanding past cultures through what has been left behind. "Do these developments represent a 'New Archaeology'? Well of course it depends on the point of view of the observer and what the observer wishes to see. However, it does seem difficult to sustain the view that the character, scale and rapidity of recent change is of no greater significance than that experienced in other twenty-year spans of archaeological development. We seem rather to have witnessed an interconnected series of dramatic, intersecting and international developments which together may be taken to define new archaeologies within a New Archaeology; whether we choose to use these terms or avoid them is then mainly a personal, political and semantic decision” (Clarke).

Legacy

“Lewis R. Binford, SMU Distinguished Professor of Anthropology, died April 11 in Kirksville, Mo. During his 40-year career as an archaeologist, Binford transformed scientists’ approach to archaeology, earning a legacy as the “most influential archaeologist of his generation,” according to Scientific American” (SMU). As you can see, Lewis Binford is said by many to be the most influential archaeologist of him time. He was able to change the whole way archaeology was performed. He first started gaining the spotlights in 1962 while he was still an assistant professor at the University of Chicago. It was at this time that he wrote his article “American Antiquity”. In this, he proposed a new way for archaeologists to perform their work. Instead of doing what they had been doing all along, which was simply cataloguing their findings, he proposed that they studied what these artifacts revealed about the history of the culture and delve deep into the meaning of their findings. He consistently said to bring scientific methods into the research, using statistical sampling, new research designs, and hypothesis testing. This new way of doing archaeology would become known as “New Archaeology”. This new way of doing things made archaeology much more scientific in nature. Though he was an American Archaeologist, his influence spread across the entire globe. Binford also received many awards including honorary degrees from the universities of Southampton and Leiden, a membership in the National Academy of Sciences, the Huxley Memorial Medal from the Royal Anthropological Institute of Britain, was elected a fellow of the British academy, and a lifetime achievement award from the Society for American Archaeology. There is also a fund known as the Lewis R. Binford Fund for Teaching Scientific Reasoning in Archaeology through the Society for American Archaeology which still accepts donations.

Works Cited

Digital

• Clarke, David (1973). "Archaeology: the loss of innocence". Antiquity 47. pp. 6–18• Gamble, Clive. "Lewis Binford Obituary." The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 17 May 2011. Web. 01 May 2016.

• Lekson, Stephan. "The Legacy of Lewis Binford." American Scientist. The Scientific Research Society, n.d. Web. 01 May 2016.

• "Lewis Binford." The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group, n.d. Web. 24 Apr. 2016.

• "Lewis Binford." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 01 May 2016.

• Meltzer, David. "Lewis Binford - Anthropology - Oxford Bibliographies - Obo." Lewis Binford. Oxford University, 28 May 2013. Web. 18 Apr. 2016.

• Miller, Stephan. "Archaeologist Binford Dug beyond Artefacts." The Archaeology News Network. The Wall Street Journal, n.d. Web. 01 May 2016.

• Rajendran, S. "Legendary Archaeologist Lewis Binford Passes Away." The Hindu. N.p., 13 Apr. 2011. Web. 17 Apr. 2016.

• "SMU's Lewis Binford Left Legacy of Change, Innovation." SMU. Southern Methodist University, n.d. Web. 24 Apr. 2016.

Pictures

• Miller, Stephan. "Archaeologist Binford Dug beyond Artefacts." The Archaeology News Network. The Wall Street Journal, n.d. Web. 01 May 2016.• Luz, Ricardo. "Archaeology: Lewis Binford's Population Pressure or Equilibrium Theory – An Overview." JFO Journals from Oceania. N.p., 08 Apr. 2015. Web. 01 May 2016.

• "Nunamiut-Ethnoarchaeology." Amazon. N.p., n.d. Web. 01 May 2016.

• "Lewis Binford." The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group, n.d. Web. 24 Apr. 2016.

• Wilford, John Noble. "Lewis Binford, Leading Archaeologist, Dies at 79." The New York Times. The New York Times, 22 Apr. 2011. Web. 01 May 2016.