The Washing Away of a Culture

The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe

Andrew Beyer and Zoe Russell

Contents

Introduction

The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, also known as the Isle de Jean Charles Band, faces displacement due to the impact of rising sea levels in southern Louisiana. This non-federally recognized, or unrecognized, Tribe is forced to relocate to higher ground, which is causing the loss of ancestral burial grounds and a disruption to the community's way of life on the Isle de Jean Charles ("The Island," n.d.). Communities around the world are experiencing the effects of climate change: rising sea levels, increasingly erratic weather patterns, an increase in wildfires, and longer periods of drought. Rarely discussed is the effect that this has on the physical land of Indigenous communities, especially concerning their ancestral grave sites and living conditions. Tribes that are unrecognized face even greater challenges, such as experiencing difficulty when attempting to receive funds to relocate or not being included in climate change policy conversations in their state or federal governments (Steinman, 2012). This is gradually improving, but for many Indigenous communities, like the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, it is too late.

Climate Change and Indigenous Communities

As climate change continues to ravage communities around the globe, Indigenous communities persistently face unique challenges. The economies, settlement locations, and cultural lifestyles of Indigenous communities around North America are under immense threat. Indigenous peoples are often left out of climate change activism discussions at the state and federal levels, which has led many universities to develop research projects that aim to represent Indigenous communities. One such example is a Climate Change Adaptation Plan in response to sea level rise for the Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana, which is conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). This plan helps the Chitimacha Tribe prevent, plan, and prepare for current and future environmental challenges by improving education and awareness of climate change. The Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana is one of four federally recognized tribes in Louisiana, which means it receives direct federal funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the U.S. Department of Housing and Development (HUD), the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), and other disaster-relief organizations. Many non-federally recognized tribes are state-recognized, so they can receive federal funding and support from these organizations only if advocated by the state (“A Climate Change Adaptation Plan,” n.d.). Although the Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana is receiving direct federal assistance, Indigenous communities are extremely vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

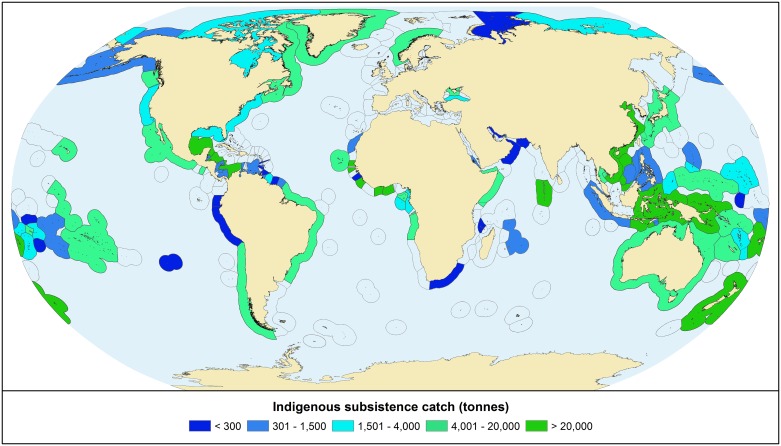

The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, a combination of Mississippi Biloxi, Louisiana Chitimacha, and Louisiana Choctaw heritages, is an unrecognized Tribe of Louisiana, so it is left out of the USGS adaptation plan and FEMA funding. The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw and other unrecognized tribes struggle to get assistance in prevention and mitigation planning. Additionally, research is often rarely conducted on their lands, which often results in an absence of federal resettlemt funding (Steinman, 2012). Unrecognized and recognized coastal Indigenous peoples are also faced with economic and food security challenges. Coastal Indigenous peoples consume seafood at a rate of 74 kg⋅capita-1⋅year-1, while the global average (on a national level) is 19 kg⋅capita-1⋅year-1. The map shown below displays Indigenous peoples' substantial reliance on seafood, so the sinking of coastal Indigenous land is driving these communities to find new food sources and economic opportunities (Cisneros-Montemayor et. al., 2016). This proves one aspect of grounded normativity, which is a term often used to describe the land as the base of political systems, economy, and culture (Simpson, 2017). The disappearing land disrupts the interconnectivity included in the grounded normativity concept.

Burial and ceremonial sites are also vanishing due to rising sea levels. On the northern Gulf Coast of Florida, archaeologists have discovered submerged stratified archaeological sites (McFadden, 2014). The northern Gulf Coast, specifically the Big Bend Region, is home to many Indigenous groups. Among these submerged stratified sites are Paleoindian burial and ceremonial sites, which is important ancestral history for the Indigenous people of the Big Bend Region (Faught, 2004). Louisiana’s striking similarities in landscape to this region demonstrates the inevitable future of Indigenous burial and ceremonial sites. Tribes like the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw are being forced to relocate to higher ground, leaving their burial sites behind to be forever destroyed.

History of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw

Shortly after the passing of the 1830 Indian Removal Act, according to the Tribe's oral history, a Frenchman married a Native American woman and was subsequently disowned by his own family. They decided to move to an island that had been often used by the Frenchman’s father, Jean Charles Naquin, to do business with a pirate. The couple’s children married those from the combined Biloxi-Chitimacha Tribe and the Choctaw Tribe who moved onto the island to create the Isle de Jean Charles Band of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe. For many decades, the United States government considered the land of the Isle de Jean Charles to be uninhabitable, but the Tribe was able to buy the land by 1880 ("The Island"). The French-speaking Tribe gained state recognition from Louisiana in 2004, allowing them to get state funding for education, resettlement, housing, and employment opportunities (Hackenburg, 2004). The Tribe has always survived from gardening and fishing, however 98% of the land is now submerged in water due to rising sea levels since the 1950s (Mei, 2017). State recognition has been proving to be revolutionary for the Tribe in regard to resettlement efforts.

Tribal Displacement and Resettlement

The disappearing landmass of the Isle de Jean Charles has caused a population of nearly 300 residents to drop to a startling 40 inhabitants (Jarvie, 2019). There once was a time when the Tribe hoped that their displaced members would be able to reunite those remaining on the island. Unfortunately, it is too late. The island was once over 22,000 acres in size, but has now dwindled to under 320 acres and is still shrinking (“About the Project,” n.d.).

The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe decided to resettle after the United States Army Corps of Engineers realigned the Morganza Tribe to the Gulf Hurricane Protection Levee in 2001. The Army Corps’ action left the Isle de Jean Charles Band out of their last chance for protection of their land. This ultimately forced Traditional Chief Albert Naquin and the Tribal Council to make the decision to resettle (“Tribal Resettlement,” n.d.).

Beginning in the 1950s, many Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribal members have been displaced and relocated inland due to their homes and properties being destroyed by the Gulf of Mexico. Gaining state-recognition in 2004 finally gives the Tribe the ability to provide resources for all members to resettle. In preparation for resettlement efforts, the Tribal Council conceived the “Isle de Jean Charles Resettlement Project.” State-recognition allowed the Louisiana’s Office of Community Development to include the Isle de Jean Charles Resettlement Project in the state’s response to a Federal “Notice of Funding Availability,” which accepted community responses to the effects of climate change. On January 25, 2016, the Isle de Jean Charles Band was awarded $48 million from this funding opportunity to aid in their resettlement efforts. The Tribal Council was quite hesitant in receiving these funds because $48 million is only a fraction of the entire grant. The rest of the money is going to Louisiana to auction off property from the resettled location to the public that the Isle de Jean Charles Band does not use. The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw worries that their new land will be under threat once again (“About the Project”).

The Tribe uses the money to work with local colleges, universities, nonprofits, communities, and other tribes. The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw is receiving assistance from Grounded Solutions Network & Burlington Associates and Citizens' Institute on Rural Design in order to provide and design homes and property for tribal members. Much of the funds will be used in the process of building on the resettled land (“Tribal Resettlement”). The resettlement location is still yet to be determined, but a few potential sites have been located. The location will be large enough so that displaced members and current Isle de Jean Charles residents can live on the land (“About the Project”). The reuniting of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw members is soon to come.

Since many other coastal Indigenous tribes are making the same decisions to resettle, the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw are continuing to show support to these communities by mutual sharing of models for resettlement and sustainability (“Tribal Resettlement”). As the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw community looks forward to beginning a new era, they will forever mourn the loss of their traditional ways of life and burial grounds.

Further Reading on Tribal Resettlement in the United States

Alaskan Indigenous Community Responses on Climate Change

Nanumea, Tuvalu. Human Organization, 74(4), 341-350.

Anthropological Research on Indigenous Communities and Climate Change

References

11(12).

recognition

4. Isle de Jean Charles Band. (n.d.). The island. www.isledejeancharles.com/island.

5. Isle de Jean Charles Band. (n.d.). Tribal Resettlement. www.isledejeancharles.com/our-resettlement.

sinking-louisiana-island-20190423-htmlstory.html.

67(4), 179-195.

9. Mei, A. (2017). Rise: a guide to boundary resistance. Landscape Architecture Frontiers, 5(4), 125+.

10. Simpson, L. B. (2017). As we have always done. University of Minnesota Press.

Cited Images

one, 11(12).

Image 3 Isle de Jean Charles Band. (n.d.). The island. www.isledejeancharles.com/island.