Navajo

Language and Revitalization

Evan Karlson

Introduction

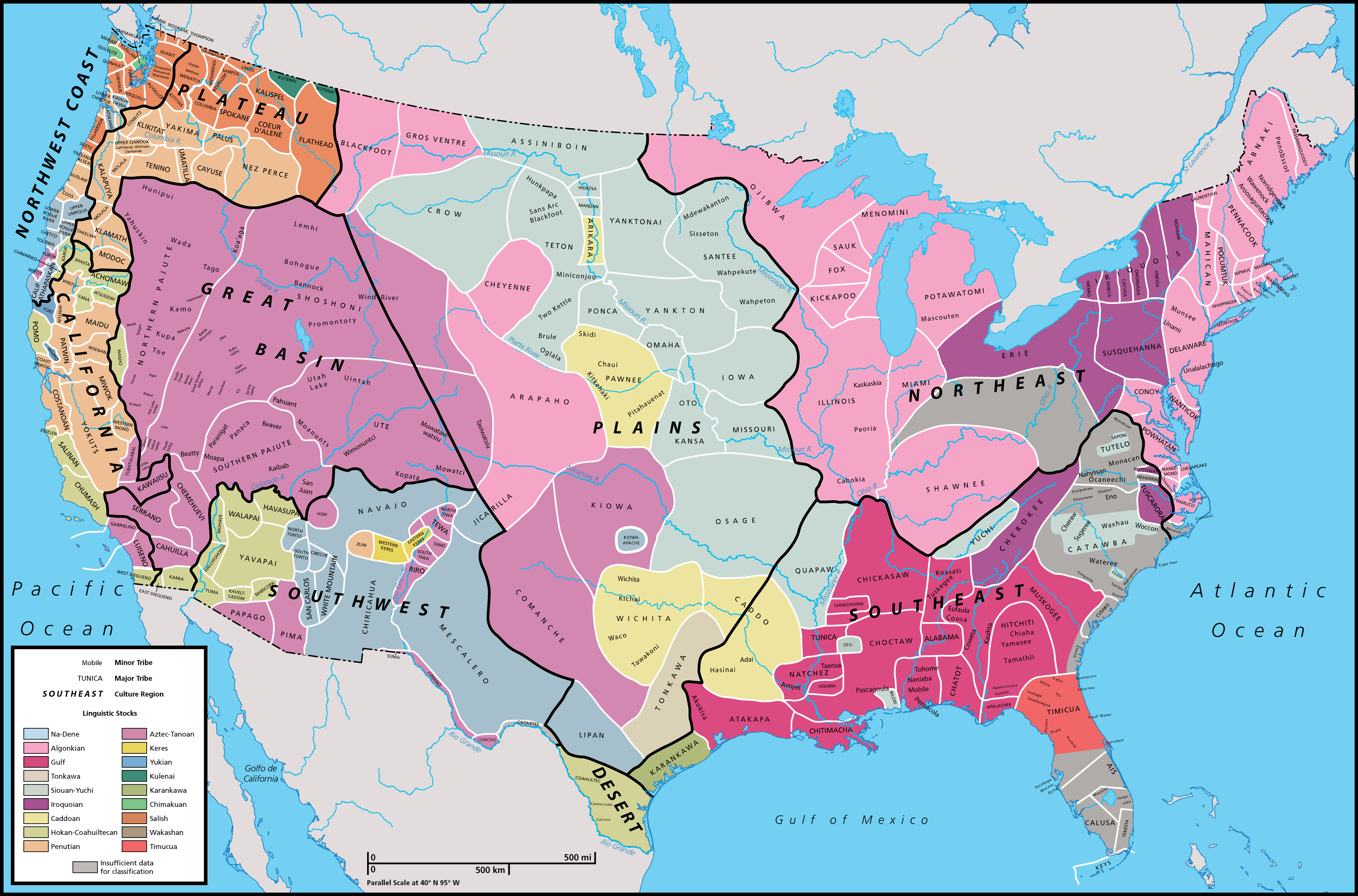

As you read this sentence, are you actually giving thought to what language with which you are deciphering the words you read? Most likely, you have not. Language, the ancient construction with which humans made society among other things, a powerful weapon of survival is an instrument of immense value. English next to Spanish, is the national language of government and business. Yet, according the U.S. Census Bureau there are over 169 existing Native American Languages in the United States. (Bureau of Census, 2011) The Navajo rank first amongst languages spoken with a speaker base of around 350,000 speakers. (Bureau of Census, 2011) This figure may seem minute, however this number is equivalent to the entire population of the nation of Belize. (World Bank Population) The fight for the survival of the Navajo language entails a substantial history that spans multiple centuries of colonization, cultural targeting, and revival. Survival and revitalization of the Navajo Language and its flourishing, entails a story that offers hope for the survival of all Native Languages.

The Origins of Catalouged Navajo

Navajo has been spoken for thousands of years, however the historical beginnings of the struggle for preservation can be traced to the passage of the Congressional Passage of the “Civilization Fund” in 1819. (Lockhard, Louise) This fund passed in the name of instilling “habits of civilization” enveloped a greater drive for English language enforcement however simultaneously called for the cataloguing of Native Languages. (Lockhard, Louise) In the case of the Navajo language, a Captain for the United States Army by the name of Captain J.H. Eaton was ordered to translate a list of over 450 Navajo words. (Lockhard, Louise) The efforts of Captain Eaton were the first in modern recorded history in which any attempt had been introduced to record, catalogue, and preserve Navajo. Naturally, the efforts to catalogue Navajo were not performed with the intentions of the tribe, however this process has allowed in retrospect to ensure the future survival of Navajo. Between 1863 and 1884 during the period of forced relocation to reservations, mission schools served as the only instrument of language preservation. In particular, the Navajo mission school at Fort Sumner, New Mexico served through its multiple handlers, an attempt to Christianize the Navajo but one in which the missionaries actively sought to learn the language of the sinners they attempted to save. (Lockhard, Louise) The first Navajo dictionary was compiled by Chee Dodge (First Tribal Chairman of the Navajo) and Washington Matthew’s (Fort Defiance Post Surgeon) in the late 1890’s. (Lockhard, Louise, 1995)

John Collier

The efforts to catalogue Navajo reached their zenith under John Collier’s tenure as Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs between 1933 and 1945. Collier set forth motions to establish programs in bilingual education, adult basic education, Indian teacher training, and in-service education. (Lockhard, Louise) Although once again the overarching reasoning for Collier’s Measures lay in English language education, an equally great president was placed on cataloguing and preserving native languages. The efforts of Colliers, Chee Dodge, and others establish the historical insight necessary to comprehend the modern issues surrounding Navajo.

Contemporary Challenges

The challenges for language preservation in the modern era are quite different than those seen between the 19th and 20th centuries.

Where before the largest barrier lay in a lack of speakers of both Navajo and English, today the omnipresence of English threatens many heritage languages.

Although the active threat of cultural assassination is gone, more and more native children are growing up with English as opposed to their heritage tongue.

The Navajo fair in a much better situation compared to other tribes. Navajo continues to be actively taught in the community to this day.

As late as the early 1980’s, a study from one Navajo language school indicated that over 90% of the students entering the school were fluent Navajo speakers. (Lee, Tiffany)

This is a stark contrast to other communities where the number of fluent speakers is dwindling, or already low.

Yet, that being said as time progresses the number of Navajo speakers born to strictly Navajo household will continue to diminish as time progresses.

Moreover the challengers of navigating Navajo in an English dominated envoirments presents difficulties.

Many Navajo's see their language as threatened and under attack from greater American society.

The pervasive attidute felt by many Navajo, is that "mainstream" America actively suppreses the usage of Navajo. (Webster, Anthony)

Webster points out that issues such the banning of Navajo in an Arizona restaurant, leave many Navajo concerned about the status of their language. (Webster, Anthony)

This concern highlights an enviormental factor that could prove difficult in continuing the process of revitalization.

Future

The most pressing matter facing revitalization is ensuring that future generations are equipped to navigate Navajo, as it remains now more than ever a powerful tool of cultural sovereignty. Navajo youth continue to be invested in their language viewing it as a powerful tool of cultural heritage and pride. (Lee, Tiffany) Moreover, Navajo youth are increasingly aware of language marginalization within their own community helping ensure that active use of Navajo does not become a historical footnote. (Lee, Tiffany) As time progress the future of Navajo as a language, is undoubtedly in a solid position to continue to be spoken widely and valued as an instrument of cultural sovereignty and ownership. That being said, even if pure Navajo becomes non-existent in the future, hope is not lost. Anthropologist Barbara Meek argues that most substantial barrier to language re-vitalization is confining a heritage language to “traditional” standards. (Meek, Barbara) In essence, she argues that so long as any heritage tongue is held to historical standards of purity, it will limit its potential for growth. However, as history has shown Navajo has continued to adapt alongside the changing historical landscape. Moreover, youth interest ensures that future generations will undoubtedly continue to speak Navajo alongside English. Language remains a powerful tool in asserting Native sovereignty. Through centuries of conquest, reservations, and assimilation, Navajo stands as living testament to cultural legacy, heritage, and language of a people dedicated to the survival of their unique legacy.

Bibliography

United States Census Bureau. 2011. Native North American Languages Spoken at Home in the U.S.: 2006-10 : American Community Survey Brief Reports; 2011 ASI 2316-15.40;ACSBR/10-10.

Louise, Lockhard. 1995. New Paper Words: Historical Images of Navajo Language Literacy. American Indian Quarterly 19 (1): 17-30.

Tiffany S. Lee 2009. Language, Identity, and Power: Navajo and Pueblo Young Adults' Perspectives and Experiences with Competing Language Ideologies. Journal of Language, Identity and Education 8 (5): 307-20.

Barbra A. Meek 2010. We Are Our Language: An Ethnography of Language Revitalization in a Northern Athabascan Community. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

"Population” The World Bank Total Population, accessed April 17, 2016.

Webster, Anthony K. 2010. Imagining navajo in the boarding school: Laura Tohe's No Parole Today and the Intimacy of Language Ideologies: Imagining Navajo in the Boarding School.

Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 20 (1): 39-62.

Further Reading

Barbra A. Meek 2010. We Are Our Language: An Ethnography of Language Revitalization in a Northern Athabascan Community.

Jacob W. James, Sheng Yao Cheng, and Maureen Porter. 2015. Indigenous Education : Language, Culture and Identity.

Grenoble, Lenore A., and Lindsay J. Whaley. 2006. Saving Languages: An Introduction to Language Revitalization.

Wyman, Leisy Thornton. 2014. Indigenous youth and multilingualism: Language Identity, Ideology, and Practice in Dynamic Cultural Worlds.