Native Hawiians, Tourism, and Cultural Appropriation

Hawai'i

By: Kylie Glazier

Introduction

From foreign contact to statehood, the appropriation of Hawaiian culture for economic and corporate gain has negatively affected Native communities of Hawaii. The tourism industry completely contradicts and destroys its host culture while simultaneously bleeding the culture dry of its cultural values by turning their culture into a commodity. It demonstrates the moral injustice of consciously putting financial gain ahead of preserving and respecting its native host culture. Native Hawaiian communities live in political and cultural degradation with tourism industries encroaching on their ways of life. The very institution that is completely dependent on Hawaiian culture is knowingly worsening the preservation of its hosts beautiful culture.

History from Western Contact Timeline 1778-1960

1778: Captain James Cook discovers Hawaiian Islands

1820: Christian missionaries arrive to the Islands

1826: United States and Hawai'i enter a treaty of commerce

1891: Queen Lili'uokalani's reign beigns

1893: Hawaiian's monarchy is overthrown by the United States government

1894: Republic of Hawai'i is established

1898: U.S. Congress passes resolution to annex Hawai'i

1941: Pearl Harbor

1959: Hawai'i becomes the 50th U.S. state

From Contact to Statehood

Contact between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Hawaii created a downward spiral of loss of cultural identity between the Native Hawaiian communities. During the 1890s the United States became a world power by gaining control over the Caribbean Islands and other land surrounding the North American continent subsequently making contact with the Hawaiian Islands (Van Dyke, 200). Commerce treaties between the United States and the Hawaiian monarchy soon acquired political motivations due to expansionist ideologies of the time and the power hungry U.S. government looking for further control of surrounding areas (Van Dyke, 203). After over a century of Western contact, the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown and the annexation of Hawai'i by the U.S. government passed in 1898 despite unanimous protest of the Native Hawaiians whose loyalty still laid with their King and Queen. Two years after the annexation of 1898, Hawai’i became a United States territory in 1900 and later the fiftieth state in 1959 (Kamahele, 76). Unethically acquiring the Kingdom of Hawai’i, even to this day, the legitimacy of this annexation under U.S. constitutional law is rightfully scrutinized (Van Dyke, 212).

Tourism

Commodities like sugar and pineapple were economic driving forces that the United States capitalized on however after statehood, the U.S government began to see Hawai'i land and culture as another product to exploit because of the socioeconomic changes in mainland American society (Diamond, 25). The 1950s newly emerged American middle class began to have access to international travel. Jet liners, a prosperous economy, more leisure time, and an intrigue of experiencing places untouched by American capitalism and industrialism caused an influx of tourism into the Hawaiian Islands (Brush, 16). During this time tourism expanded and soon advertised Hawai'i as America's own tropical-get away right in their backyard and consequently, tourism became the islands main source of revenue (Mak, 16). The U.S. government and tourist corporations viewed Hawai'i as theirs to use,take,and exploit (Taum, 33). In the 1960s 'Hawai'i residents outnumbered tourists by more than two to one' while by todays estimates ‘tourists outnumber residents by six to one and outnumber Native Hawaiians by thirty to one’ (Trask). Native communities are plagued with adverse effects from a continuously growing tourism industry to this day that did not happen with and still continues without Native Hawaiian’s consent (Apo, 3).

With the states major economic driving force focused on economic grow rather than cultural preservation the tourism industry has been and still is a threat to cultural and community identity that has ultimately diminished the status of Native Hawaiians among the states population (Taum, 31). Hawaiian tourism is centered round culture as its commodity and focal point to sell tourists as an authentic Hawaiian experience for those who want to exploit an ethnic subculture for their own entertainment. In reality however, the globalization and tourism industry are destroying the very core of what they are marketing (Darowski). The advertisement of Hawaiian tourism paints a picture of a primitive yet romantic and erotic culture that can be consumed as 'safe and soft savagery' catered to the consumers ideal 'other'(Diamond, 19, 26).

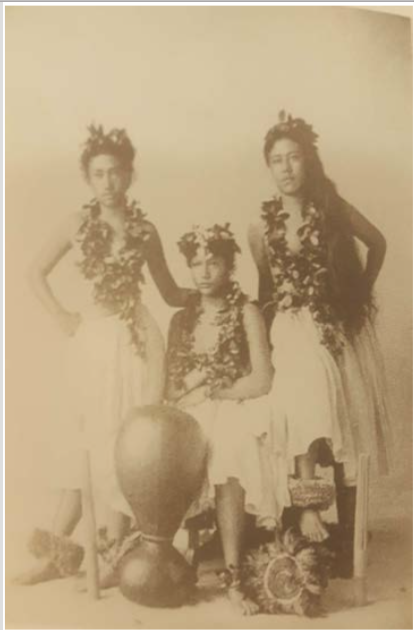

The degrading marriage of tradition and tourism 'is a deal with the devil that perpetuates exploitation of Native people's environment, values, cultural practices, and sacred places' (Apo, 2; Diamond, 14). Many Indigenous peoples have found themselves in economic poverty due to the infiltration of tourism industries throughout every aspect of their life and are forced to sell themselves into 'cultural prostitution' to make a living. One of the most culturally exploited aspects of Hawaiian cultures is the ceremony of Hula, which has been reshaped into the stereotypical image of a half-Caucasian, scantily clad, stick thin, amalgamation of Polynesian 'native' women used to sell trips to the Hawaiian Islands to mainland Americans (Trask). Not only is the sexualized version of a hula dancer emotionally degrading and ethically wrong but it is also a completely inaccurate representation of what Hula is, what it is used for, and who practices it. This once sacred ritual of dance has now become a kitsch icon of Hawai'i and its now hybridized culture being exploited for commercial gain, stripping it of its cultural meaning to Native Hawaiians (Diamond, 26).

History of Hula

"Hula is the language of the heart therefore the heartbeat of the Hawaiian people..."-King Kalakaua

The philosophical concept of aloha represents love, respect, understanding, and Hula is aloha in action and it makes up the very roots of the Hawaiian society (Reed). The superficial hula shown to tourist, in hotels, on stages, choreographed by non-natives in business suits has been ‘stripped of its original meaning, context, movements, and location’ (Brush, 7). The word and practice of hula connects Native Hawaiians to their ancestors and their heritage (Kamahele, 77). Hula’s origin is in direct connection with the gods used as a religious practice and the embodiment of chant to worship, honor, thank, and connect with the old gods (Brush, 8; "The Hula"). Variations of the dance span across all of the Hawaiian Islands however all forms of hula dance connect back to the core values of what it means to be Hawaiian. The physical and symbolic representation that Hula has shows that this sacred dance is the absolute essence of Hawaiian culture: ‘Hula is the language of the heart therefore the heartbeat of the Hawaiian people’(Mederios, 19). Unfortunately, tourism has altered this sacred ritual drastically and through Hula, we are able to see the rapid loss of a beautiful culture.

As the cultural tourism industry in Hawai’i grew exponentially corporations and tourist expectations dictated the appearance of Hawaiian culture (From A Native Daughter, 137). Cultural tourism began because of the peaked interest of experiencing some form of ‘otherness’, mainly the ‘cultural uniqueness of the lifestyles of subnational ethnic groups’ considered backwards by tourists (Linnekin 1, 6). However, as this ‘ideal’ Hawaiian experience developed, tourists wanted a culture different from theirs but not shockingly savage or primitive. The ceremony and dance of Hula became the center of cultural tourism because it ‘narrowed down to those aspects of culture that are subject to aesthetic appreciation’ (Linnekin, 10). The image of a Hula dancer appealed to tourists because of its comfortably different comparison to modern society. Soon the tourism industry utilized the image of a Hula girl, destroyed its cultural meaning, and sexualized the Hula dancers as a fetishized symbol ‘draped in lei and holding a ukulele’ to provide the desired destination image (Brush, 7; Diamond, 26). Rather than representing their ancestors, their values and cultural traditions, and their honor, the Hula girl was destroyed and became objectified to project an image of Hawai’i that would create money (Brush, 23).

The tourism industry’s altering of Hawaiian culture and the expectation of the country as a destination image drastically changed how Hulas were danced (Brush, 2). Rather than performed by soloists in a religious context on sacred land, the new age hula, ‘auana hula, was performed in hotels and on stage for entertainment and money which eventually severed the ties of its spiritual meaning. Hulas were performed in a chorus of ‘girls trained to dance exactly alike and danced hulas deemed entertaining’ for tourist spectacles made up of various Polynesian and Hawaiian dance styles diluting Hawaiian heritage (Diamond, 25; Brush, 7). Alterations made for a more ‘aesthetically pleasing’ experience were hula dancers wore more provocative, historically inaccurate costumes and only women who were half-Caucasian with lighter brown skin, black hair, dark eyes, and underweight ‘were allowed to perform regardless of whether or not they were of Hawaiian ancestry’ resulting in stereotypical images seen today in relation to Hawaiian culture (Brush, 23). Hula became kitsch entertainment asking nothing of the viewers but money while the deeper meaning of losing Hula traditions seriously degraded Native Hawaiians connection and pride for their culture. The control by tourism over the Hula, which represents the essence of Hawaiian culture, truly shows the power tourism has over the bodies of the dancers and the selling of a culture for economic benefit. However, despite the discourse between the preservation of Hawaiian culture and its abuse inflected by tourism, Native movements and efforts have been made in the last 60 years to stand up and fight for their culture.

The Hawaiian Renaissance

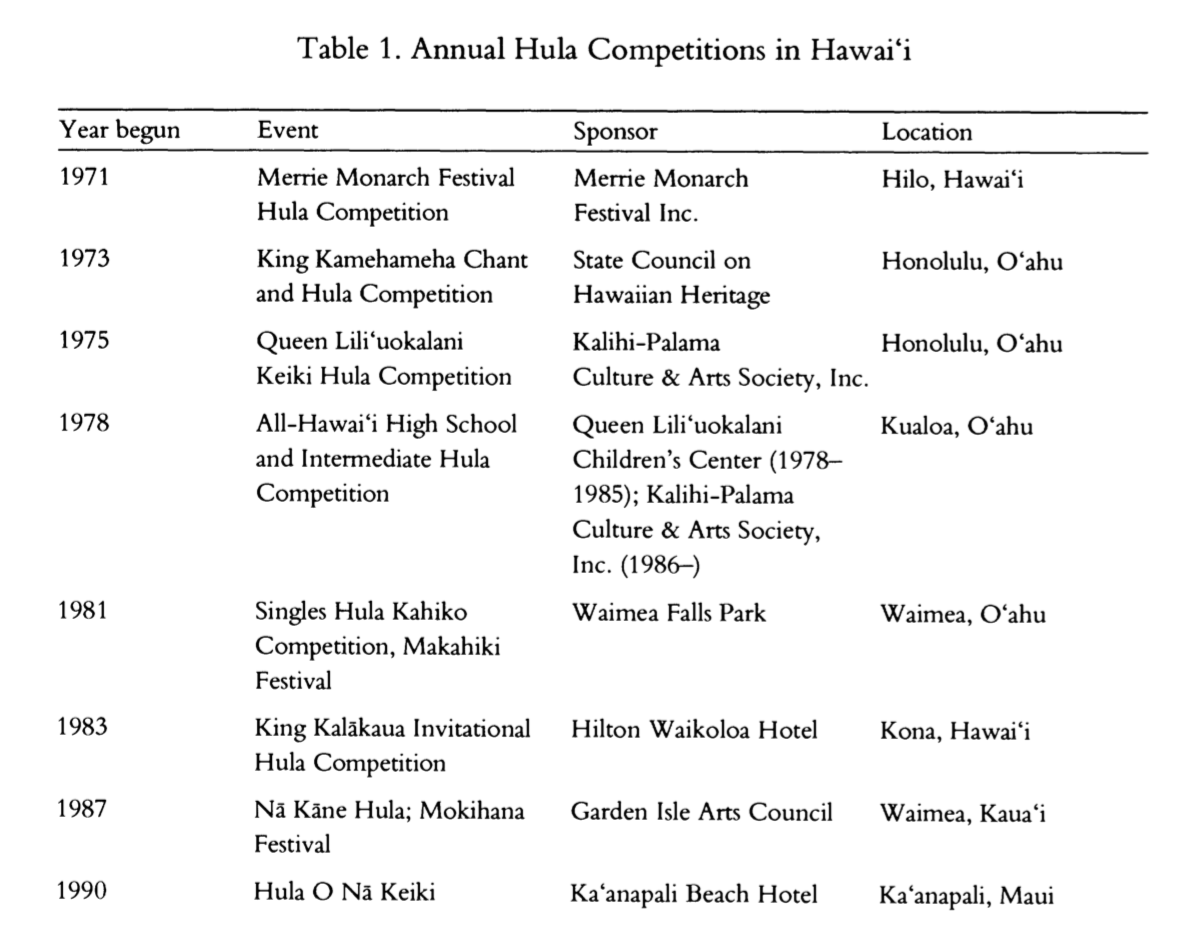

By the mid-twentieth century hula had become ‘commercialized and westernized to the point that it no longer resembled its ancient form’ or held the same cultural meaning (Hong, 16). However, political unrest advocating for First Hawaiian rights and independence alongside protests against the alienation Hawaiians faced due to tourism land development manifested in the form of a vigorous ethnic identity and cultural revival called the Hawaiian Renaissance in the 1970s to present (Hong, 17; Stillman, 360). This ethnic and cultural revival spiraled into a resurgence of all things Hawaiian such as music, language, sports, and traditional hula plus male hula after decades of sexist oppression by tourism industries (Kanahele, 3; Stillman, 360). Hawaiian culture and history was implemented into elementary and secondary academic curriculums initiating cultural awareness, interest, and pride among Native Hawaiian youth in an effort to create a sustainable cultural movement (Stillman, 360). Soon national interests were peaked to preserve, practice, and share the tradition of hula through national hula competitions such as the Merrie Monarch Festival and the King Kamehameha Celebration Hula Competitions to name a few (Kanahele, 4).

Preserving the tradition of hula has been a top priority for the Native Hawaiian community since the late 1960s through the implementation of large hula competitions and cultural festivals (Torgersen, 56). These annual hula competitions are shown in venues of high visibility and prestige with venues able to hold almost ten thousand people. The competitions showcase the traditions of hula, its practice, and its cultural relevance that helps the perpetuation and preservation of the hula tradition (Torgersen, 57). With such a large following and participation, the competitions pride themselves on the showcasing of traditional hula dances and todays interest is ‘greater for the ancient than the modern hula…the more traditional the dance, the keener the interest” (Kanahele, 4). These competitions and festivals started in the 1970s have helped immensely in contemporary hula’s traditional meaning and value, which shows how its rightful owners have taken it back from the tourism industries of Hawai’i.

Hula Competitions and Festivals

Two of the most prestigious hula competitions in Hawai’i are the Merrie Monarch Festival and the King Kamehameha Chant and Hula Competition. Established in 1971 as a direct result of the Hawaiian Renaissance the Merrie Monarch Festival is a week-long affair following Easter Sunday located in Hilo, Hawai’i and still continues today (Stillman, 361). This festival consists of different categories such as female and male solos and groups in both kahiko and ‘auana hula styles, chants, and an exclusively female soloist category called the Miss Aloha Hula ("About"). All categories within the Merrie Monarch Festival and Hula Competition are great contrasts to what is showcased in tourist hula shows (Torgersen, 56). The King Kamehameha Chant and Hula competition was established in 1973 and takes place in O’ahu in conjunction with the Hawaiian holiday ‘Kamehameha Day presented by the State Council of Hawaiian Heritage’(Stillman, 362).

The King Kamehameha Competition has all of the same categories of the Merrie Monarch Festival however it has a combined category for men and women (Stillman, 364). Participation in these prestigious competitions are reserved for adults however children can participate in the Queen Lili’uokalani and King Kalakaua Invitational’s which expose the younger generation to the importance of hula and the perpetuation of Hawaiian traditions (Stillman, 364).

These festivals and competitions bring a sense of cultural identity and pride among Native Hawaiians that had been lost due to Western contact and tourism. These competitions and festivals are more than showcasing traditional hula, they also display traditional Hawaiian rituals, communal feasting, entertainment involving traditional Hawaiian music, sports, and displays of multiple skills and talents unique to Native Hawaiian communities (Stillman, 357). ‘Hula studios holding classes, workshops, and seminars throughout the year to teach the art of hula, the meaning of Hawaiian chants and songs, the Hawaiian language, the making of Hawaiian clothing and crafts and the history of Hawaiian people’ are all to create and perpetuate the essence of Hawaiian culture and mark its importance in contemporary society (Hong, 17). The types of hulas danced at these competitions are hula kahiko, the ancient pre-contact style with a melody chanted not sung companied by native instruments with vigorous and robust sharp movements with the arms, hands, and legs. The hula ‘auana is the modern style danced in Westernized style with melodies sung alongside guitar and ukulele’s showcasing more graceful and fluid gestures of the hands and arms (Stillman, 366). The songs sung are to only be in the native Hawaiian language and are poetic renditions of puha (songs for the gods), ‘ala’apapa (dedicated to historical people) and ku’I (Westernized songs) in which the hula is danced to (Stillman, 366-7).

The cultural revival through hula competitions ‘develops and augments a living knowledge of Hawaiian arts and crafts through demonstrations, exhibitions, and performances of the highest authenticity’ to perpetuate and protect the culture of the Hawaiian people ("About"). All of the proceeds from these festivals and competitions support educational scholarships, workshops, seminars, and the continuation of the event ("About"). ‘The Merrie Monarch Festival and the King Kamehameha Chant and Hula Competition strengthened the non-tourist presence of hula as did programs and workshops sponsored by state and local organizations that sponsor’ the celebration and preservation of Hawaiian culture ("About").

References

“About the Merrie Monarch Festival.” The Merrie Monarch Festival. Accessed April 6, 2018. http://www.merriemonarch.com/about/.

Apo, Peter, Kanahele, Dennis, Logan, Cherlyn and Dr. Davianna McGrefor. “Planning for sustainable Tourism.” Presentation for Planning for Sustainable Tourism in Hawai’i Project by Hawai’i State Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism, Honolulu, Hawai’i, August 2003.

Brush, Molly. “Royal Hawaiian Dance: How Hotels Commodified the Hula.” Senior Thesis, Barnard College Columbia University, 2005.

Darowski, Lukasz, Provost, Casey, Sorochuk, Jason and Jordan Strilchuk, “Negative Impact of Tourism on Hawaii Natives and Environment,” Lethbridge University Research Journal 1, no. 2 (2007).

Diamond, Heather A. “Cultural Intervention in America’s Eden”. In American Aloha: Cultural Tourism and the Negotiation of Tradition, University of Hawai'i Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqtd3.

Hong, Cesily. “The Power of the Hula: A Performance Text for Appropriating Identity Among First Hawaiian Youth.” The University of San Francisco Doctoral Dissertations, (2013): 1-128.

Kamahele, Momiala. “Ilio’ulaokalani Defending Native Hawaiian Culture”. In Local Governance to the Habits of Everyday Life in Hawai’i, eds. Candace Fujkane and Jonathan Y. Okamura, University of Hawai’i Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wr0h6.

Kanahele, George S. The Hawaiian Renaissance. Project WAIAHA, 1982.

Linnekin, Jocelyn. “Consuming Cultures: Tourism an the Commoditization of Cultural Identity in the Island Pacific.” In Tourism, Ethnicity and the State in Asian and Pacific Societies, eds. Michael Picard and Robert E. Wood, University of Hawai’i Press, 1997. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqr0d.

Mak, James. Developing a Dream Destination: Tourism and Tourism Policy Planning in Hawaii, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqrfp.

McDougall, Brandy Nalani. “The Second Gift”. In The Value of Hawai'i 2: Ancestral Roots, Oceanic Visions, eds. Aiko Yamashiro and Noelani Goodyear-Ka’opua, University of Hawai'i Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqsn1.

Medeiros, Megan. “Hawaiian History: The Dispossession of Native Hawaiians’ Identity, and Their Struggle for Sovereignty.” California State University San Bernardino Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations, (2017): 1-96.

Reed, Ryan R. The Meaning Behind Hula. Ryan R. Reed. 2017. Smithsonian Magazine Online, 2017. Video.

Stillman, Amy Ku'Uleialoha. "Hawaiian Hula Competitions: Event, Repertoire, Performance, Tradition." The Journal of American Folklore 109, no. 434 (1996): 357-80. doi:10.2307/541181.

Taum, Ramsay Remigius Mahealani. “Tourism.” In The Value of Hawai’i, eds. Craig Howes and Jonathan Kay Kamakawiwo’ole Osorio, University of Hawai’i Press, 2010.

“The Hula.” Ka’lmi Na’auao O Hawai’i Nei Institute. Accessed April 5, 2018. http://www.kaimi.org/education/the-hula/.

Torgersen, Eilin Holtan. “The Social Meanings of Hula: Hawaiian traditions and politicized identities in Hilo.” Master’s thesis, University of Bergen, 2010.

Trask, Haunani-Kay. From A Native Daughter. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1999.

Trask, Haunani-Kay. “Tourism and the Prostitution of Hawaiian Culture,” Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine. March 2000 accessed April 2, 2018. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/tourism-and-prostitution-hawaiian-culture.

Van Dyke, Jon M. “Annexation by the United States (1898)”. In Who Owns the Crown Lands of Hawai`i?. University of Hawai'i Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqrj4.

Amy Ku'Uleialoha Stillman. Table 1 Annual Hula Competitions in Hawai'i. 1996. JSTOR. Accessed April 13, 2018.

Hawaiians 'Before' American Influence. 1899. Murat Halstead's Pictorial History of America's New Possessions. Staging Tourism. Chicago, 1999. Accessed April 1, 2018.

Lund, Ken. The Flag of Hawaii. April, 2010. Flickr. Accessed April 10, 2018. https://www.flickr.com/photos/kenlund/4528552443/.

United Airlines Hawaii travel poster. National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution. Accessed April 12, 2018

Stanfill, Craig. Hula Girls. October, 2012. Flickr, Accessed April 11, 2018. https://www.flickr.com/photos/photo_fiend/8154319188/in/album72157631926886096/.

2018 Kahiko Gallery. April, 2018. Merrie Monarch Festival. Accessed April 9, 2018. http://www.merriemonarch.com/2018-kahiko-gallery/.