Efforts for the Revitalization of the Mi'kmaw Language

Mi'kmaw Nation

Jordan A. Fournier

Introduction

Language is seen as crucial to one's culture and identity, through past colonization efforts of Indigenous Nations, many Indigenous languages have been lost and forgotten. The efforts to revitalize these languages has exponentially grown globally, incorporating Nation, academia, and Federal support and funding. This case study looks at the Mi'kmaw language and current efforts through Universities and the Mi'kmaw First Nation to revitalize the Mi'kmaw Language verbally and digitally for future generations.

This project focuses on two major themes in the Mi'kmaq language revitalization efforts.

- University Efforts

- Language Digitalization

Mi'kmaw Nation

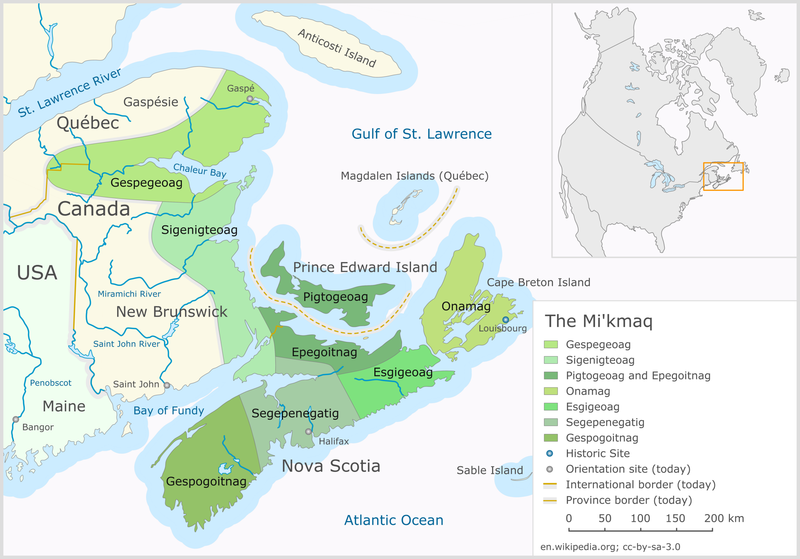

The Mi'kmaq are a tribal nation located in the North Eastern part of North America in which have been around for approximately 10,00 years, according to the newest archeological discovery. The nation is a member of the Wabanaki Confederacy (Native Languages of the Americas 2015). Their tribal territory spans over North Eastern Canada including Nova Soctia, Prince Edward Island, parts of Quebec,the north shore of New Brunskwick, the Saint John River watershed, and parts of Newfoundland. In addition to Canada, the territory also encompasses eastern parts of Maine in the United States (Cape Breton Univeristy 2019) As their territory spans a vast amount of area the Mi'kmaq have separated their territory into seven districts known to them as: Kespukwitk, Sikepne'katik, Eski'kewaq, Unama'kik, Piktuk aqq Epekwitk, Sikniktewaq, and Kespe'kewaq. Each district contains a district chief, who acts as both the local chief and a delegate for the Grand Council Sante Mawiomi (Cape Breton University 2019).

The Mi'kmaq created a close and civil relationship with European settlers, and starting in 1610, spanning over seventy years, began converting to Roman Catholicism. This conversion to European culture allowed to the Mi'kamw nation to create alliances and treaties with the British Crown (Cape Breton University 2019). The history of the Mi'kmaq and their alliances with European settlers is crucial in understanding their language history and how to approach the revitalization of their language due to the large colonial influence on the Mi'kmaq nation starting in the 1600's.

Mi'kmaw Language

The Mi'kmaw language has been battling extinction for 400 or more years, due to their connections and alliances with French and English speakers. The Mi'kmaw language has a drastic lingistical structure than English, making it easier to keep alliances by transitioning to English. In 1970, only 6,000 Natives were still speaking the language(Inglis 2004).

Additionally, many Natives were not allowed to speak their language through government coloanization efforts in both the U.S. and Canada. The US 1819 Civilization Fund Act used missionaries to enhance their goal of exterminating Native languages and culture. The Indian Act of 1876, in Canada, worked in towards the linguiicide of Native languages as well. Throughout the late 1800's and early 1900's schools were either English or French speaking, another tool used to diminish the languages (Mclvor and McCarty 2016). However, education movements in the late 1900's pushed for a change to incorporate the Native language and practices once again. The 1972 Indian Education Act, in the U.S., provided funding for language and culture programs. Additionall the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act allowed for Native to control over Native-serving schools (Mclvor and McCarty 2016). Both Canada and the US have begun efforts to increase the use of Native cultural practices and language after trying to extinguish them for many years. These efforts are growing today, especially within schooling.

Through the missionary translation of their language was misrepresentated with the modern day alphabet. This provided some obsticles for individuals trying to write and document the traditional language. For my own family, this caused the name change of my oldest sister, who is Mi'kmaq. When my oldest sister was born my dad and her mother, unknowningly, only had access to a Catholic written Mi'kmaw dictionary and not the original. Once they realized this, they were able to obtain a traditional Mi'kmaq language dictionary with the correct Mi'kmaw spelling of her middle name, Kulokowechjech meaning Little Star, they legally changed her middle name to reflect the correct indigenous spelling. It was important for them to keep the traditional spelling in order to perserve and carry on her Mi'kmaq culture.

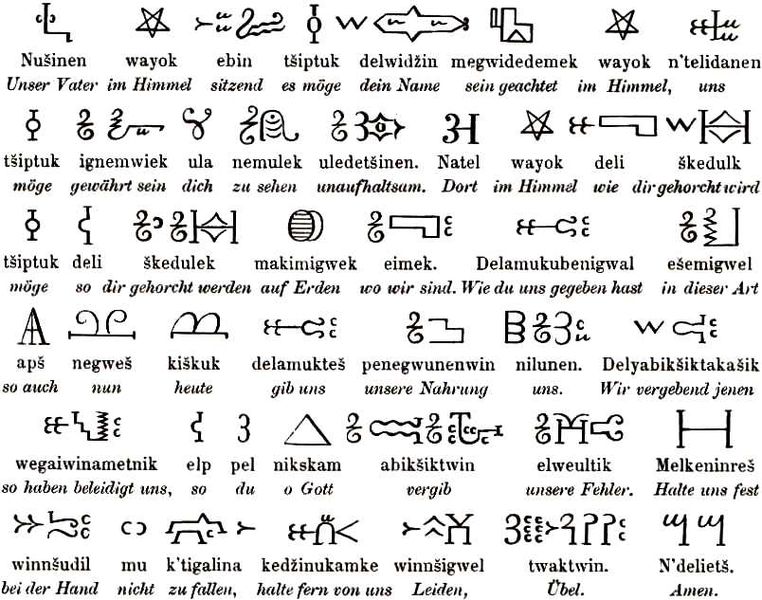

Mi'kmaq Hieroglyphics

The Mi'kmaw langauge is also written using hieroglyphics, and much of their language was translated by missionaries through spoken sounds using the modern day alphabet in 1984. In 1974, a more accurate orthography was published using their eleven constants- p, t, k, q, j, s, l, m, n ,w, and y, along with their six vowels- a, e, i, o, and u. (Cape Breton University 2019)

University Efforts

Cape Breton University- Unama'ki College

The Unama'ki College is an Indigenous education college that embraces knowledge, wisdom, and tradition of the Mi'kmaq First Nation. Faculty and staff at the college speak Mi'kmaw and offer many courses within and around the Mi'kmaw communities. They also offer a Mi'kmaw language lab. (Cape Breton University 2019)

University of New Brunswick

The Mi'kmaw-Wolastoqey Centre at the University of New Brunswick Fredericton allows for a learning environment for both Indigenous students and university students surrounding Mi'kmaq and Wolastoqey history, culture, treat rights and principles of respect, harmony, and acceptance. The center also helps Indigenous students with admission to the Univerisity's programs, student support, cultural growth and teachings from their Elder-in-Residence. The center offers many First Nation classes, including First Nation language classes. (University of New Brunswick Fredericton)

Language Digitalization

Ogoki Learning Inc.

Ogoki Learning Inc.

Partnering with the University of New Brunswick Mi'kmaw Wolastoqey Centre, Ogoki Learning Inc. has developed a free tribal language app to allowing individuals to learn Wolastoqey and other tribal languages at their own pace. The founder of Ogoki Learning Inc. is also an Anishnaabe Ojibway. (University Affairs 2018)

The app works by using english words that are then translated into Wolastoqey. When opening the app, there are 8 categories presented to the user, which include subjects such as identity and community and language of ceremony. After the user selects a category and the english word they would like to hear the word is repeated back to them aloud by, the elder-in-residence at the Mi'kmaw-Wolastoqey Centre, Imelda Perley's, a Wolastoqew, recorded voice. The centre is also working on improving the app through the addition of phonetic pronunciations and expanding the available vocabulary (University Affairs 2018).

Native Council of Nova Scotia

Native Council of Nova SoctiaThe Native Council of Nova Scotia provides a Mi'kmaw language program in which they maintain a lnaguage Resource Library where have both printed and audio material regarding the Native Languages overall and the Mi'kmaw language. They additionally publish second language learning materials, offer translation services, and are continuing research of new language learning mediums and materials (Native Council of Nova Scotia 2019).

Wabanaki Collection

Wabanaki Collection

Developed by the University of New Brunswick Mi'kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre, the Wabanaki Collection provides digital resources including links, audio, and video resources for educators and the general public regarding the Wabanaki. The resources relate to the Wabanaki worldviews, history, culture, language, and education (Wabanaki Collection 2018)

Conclusion

The revitalization of the Mi'kmaw language has been a mission among tribe members for decades. The efforts have expanding through primary school, into universities, and the community. With the use of modern technology the language revitalization efforts have allowed for the devolopement of language apps, and are using digital archives to ensure future generations have access to their language. One major drawback that factors into the new and modern form of language revitalization is that many Mi'kmaq Natives don't have access to a university education or updated technology. However, this drawback isn't a discouragement. Many elders and young natives have expanding their efforts by talking with other tribal nations of their language revitalization efforts and have learned that these tribes are much like their own.(Mi'kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre 2016). Allowing the language revitalization effort not only to keep the Mi'kmaw language alive, but will allow for the connection between other tribes and cultures.

References

Cadloff, Emily Baron. 2018. "A new app co-created at UNB aims to revitalize the Wolastoqey language" University Affairs. Link

Cape Breton Univerity. 2019. "The Mi'kmaq". Link

Inglis, Stephanie. 2004."400 Years of Linguistic Contact Between The Mi'kmaq and the English and the Interchange of Two World Views". Canadian Journal of Native Studies XXIV(2): 389-402.Link

Mclvor, Onowa & McCarty, Teresa. 2016. "Indigenous Bilingual and Revitalization Immersion Education in Canada and the USA". Bilingual and Multilingual Education. 1-17. Link

Mi'kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre. 2018. "What is the Wabanaki Collection" Link

University of New Brunswick. 2019. "Mi'kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre" Link

Native Council of Nova Scotia. 2019. "Mi'kmaq Language Program" Link

Native Languages of the Americas. 2015. "Micmac Indian Fact Sheet" Link

Univeristy of New Brunswick & Mi'kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre.2016. "Supporting Indigenous Language and Cultural Resurgence with Digital Technologies" 2-87. Link

Image References

Image 1: Wikimedia Commons. 2006. "Mikmaq State Flag" Link

Imagae 2: Wikimedia Commons. 2014. "The Mi'kmaw" Link

Image 3: Wikimedia Commons. 2012. "Micmac paster noster" Link

Image 4: Cape Breton Univeristy.2019. "Unama'ki College" Link

Image 5: University of New Brunswick. 2019. "Mi'kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre" Link

Image 6: University Affairs.2018. "A New App Co-Created at UNB Aims to Revitalize the Wolastoqey Language"Link

Image 7: Wabanaki Collection. 2018. "What is the Wabanaki Collection" Link