Intergenerational trauma

Lakota Nation

Emily O'Brien

Introduction

Intergenerational trauma, or historical trauma, is the consequence of the continued oppression and abuse of a group of people and how these past abuses continue to negatively impact across generations. This study will be looking particularly at the Lakota peoples and how colonialism in particular has impacted past generations and how that trauma has been continued and transmitted into current generations. The study will be looking at the effects of historical trauma, as well as how the Lakota people specifically are impacted. Finally, this study will be looking at the steps being taken to prevent this type of issue from worsening, as well as looking at ways to heal and improve the lives of those who are affected.

Who are the Lakota?

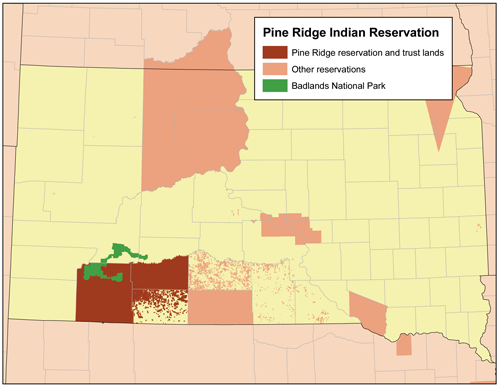

The Lakota Nation, also referred to as the Teton Sioux, consists of seven tribal bands: the Oglala, the Sicangu, the Hunkpapa, Mnikoju, Siha Sapa, Owohe Nupa, and Itzipa Cola.These bands are recognized as the People of the Plains, or the Titunwan (Stanley). The Lakota are mostly located west of the Missouri River.Pine Ridge Reservation, specifically, is home to over 18,000 tribal members and is the seventh largest reservation in North America at 11,000 square miles of land in South Dakota (The Lakota Sioux Tribe:Look at the Statistics). Pine Ridge, like many other Native communities, suffer from high poverty rates and low life expectancy (Pine Ridge Indian Reservation). The conditions are harsh and difficult to live in, however, despite all of that, the Lakota Indians continue to have a rich and diverse way of life that focuses on community and connections among the people and the earth they inhabit. The Lakota Nation has a strong and traumatic presence in the history of American colonialism, and although they continue to still face the hegemonic pressures of white society, the Lakota continue to preserver and maintain their sovereignty and dignity as a Native Indian Tribe.

Intergenerational Trauma

What is it?

Intergenerational trauma, referred to by many as Historical Trauma (and as which I will be using interchangeably with the term intergenerational trauma), was coined by Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart in 1998, and is best summarized by Teresa Evans-Campbell who describes it as “…a collective complex trauma inflicted on a group of people who share a specific group identity or affiliation—ethnicity, nationality, and religious affiliation. It is the numerous traumatic events a community experiences over generations and encompasses the psychological and social responses to such events” (320). The term stems from the inadequacy of the diagnosis of PTSD to encompass the experience of American Indian trauma (Brave Heart, Gender Differences 3). Historical trauma is not only the knowledge and effects a traumatic event has had on a community, but the lived responses that have changed how communities function internally and within the context of society as a whole. Intergenerational trauma is broken into two categories of characteristics, the first being characteristics of historical trauma events, and the second being characteristics of historical trauma responses. Historical trauma events are: widespread among the collective group, many of the members are affected, instigated by outsiders of that group, and create a collective distress within the community. Historical responses are characterized by: the ongoing degradation of wellness in contemporary members as a result of the event, the responses interact with modern stressors that influence the well-being of group members, and the risk associated with the event continues to grow throughout time. (Bombay 322). These characteristics are often applied to groups who have been associated with mass genocide and enslavement, who have dealt with colonization and erasure, and the overall destruction of culture and agency.

Criticism

Despite the potentiality of the concept, it is important to recognize the criticism of the term. It must first be acknowledged that the research done within the context of intergenerational trauma is incomplete at best. Much of the research being done does not include the multilevel framework needed to capture the scope of the issue; for example, much of the research tends to disregard the asymptomatic responses that individuals may give, which negates and undermines the resilience of these communities (Evans-Campbell 18). We need to also consider the implications that Brenda Child brings up about the oversimplification of intergenerational trauma that narrows it down to specific events, such as boarding schools, potentially placing too much emphasis on these events and disregarding other potential reasoning for the responses being given (272). It is important to consider these critiques when moving forward in this discussion, so that we are able to have a better understanding of the issue as a whole, and how this concept is still continuing to be developed in the future as a way to benefit Native American communities.

Historical Trauma and the Lakota

The Lakota tribe’s cultural traditions and past experiences make them particularly vulnerable to the affects of intergenerational trauma. “Traditional Lakota culture encourages maintenance of a connection with the spirit world. Thus, we are predisposed to identification with ancestors from our historical past” (Brave Heart, Wakiksuyapi 248). This type emotional connection to ancestors makes the grieving process much more intense, so that when a tribe is faced with traumatic events like the Massacre of Wounded Knee, forced assimilation through boarding schools, and displacement, their ability to cope is hindered and their communities begin to suffer. Along with that, in the past, the loss of mourning practices among the Lakota tribes meant that past grief was never dealt with (Brave Heart, Wakiksuyapi 248), and that grief began to pile up and manifest in unhealthy methods, which are then enforced by the continued pressures of living as minority in a westernized society, and pass those coping methods on to the following generations.

As explained by Teresa Evans-Campbell, intergenerational trauma can impact a tribe on three different levels. The first level being the individual, the second being familial, and the third being community. These types of impacts have distinct characteristics but are all interrelated and affect each other in important ways (322). The importance of the interconnectedness of these effects is vital in understanding how historical trauma is passed on, and how it continues to grow under other significant issues like poverty and racism.

How it Affects People Today: Historical Trauma Response

Individual Responses: Mental Health

Many members of the Lakota tribe suffer from mental health problems similar to that of PTSD, such as guilt, anxiety, and depression (Evans-Campbell 322). These symptoms can be directly attributed to stress of the accumulation of traumatic events within the community. This accumulation of events feed into other risk factors like poverty and racism, which then incur an even greater risk for these symptoms and without the proper resources, result in dangerous coping mechanisms like drugs and alcohol, as well as an increased risk for violence and child abuse. These types of methods are often used as “a vehicle for attempting to numb the pain associated with trauma” (Brave Heart, The Historical Trauma Response 7) and end in self-destructive tendencies. "Alcoholism, suicide, and homicide death rates are higher for Native youth than youth in the population in general. Native premature death rates are higher than those for African Americans, with 31% of the deaths occurring before 45 years of age" (Brave Heart, the Historical Trauma Response 8). The discrepancies among the rates of substance abuse and death indicate a deeper and more complex situation than what contemporary issues may account for, and thus can be attributed to as a response to the historical trauma events that the tribe have faced.

Familial Responses: Parenting

Events like the Indian boarding schools, where children were forcibly taken away from their families, have unquestionably disrupted familial dynamics within tribes. With the arrival of Indian boarding schools “Indian children were subjected to starvation, incarceration, physical and sexual abuse, and prolonged separation from families” (Brave Heart, Oyate Ptayela 112). These are all characteristics prescribed to a historical trauma event. The lack of care, empathy, and affection and the promotion of violence and neglect, left these children without the proper knowledge of how to be parents, resulting in children of boarding school victims reporting “…a history of neglect and abuse in their own childhoods along with inadequacy as parents and confusion about how to raise children in a healthy way” (Brave Heart, Oyate Ptatela 112). Lakota members also suffered the loss of culture because of the boarding schools. Many of the children faced abuse if they tried to main cultural ties and as a result they lost their language, tradition, and familial communication. This loss of culture resulted in the loss of traditional Lakota family dynamics and created a gap in the Lakota lifestyle that is difficult to overcome.

Community Responses: The Loss of Cultural Values

One of the biggest losses due to these historical trauma events and is the break down of culture values (Evans-Campbell 322). These break downs have caused a serious questioning of tribal sovereignty and have left the community social-structures unable to satisfy the needs of the community members. The loss of language also resulted in the loss of collective identity and may have left many members feeling disconnected from one another. “Another important consideration in terms of community-level impact for AIAN [American Indian/Alaskan Natives] communities is the large number of historically traumatic events that involve the loss of children” (Evans-Campbell 327). The loss of children is a universally upsetting notion that results in emotional stress and discomfit. This type of loss is especially felt by the Lakota tribe, as they tend to emphasize familial connections, specifically within the youth. Not only is the loss of children emotionally stunting for a community, but it also leaves the community uncertain of the future, because with the loss of children comes the loss of the future of the community. This stress is harmful and leaves the community in an unstable.

Community Efforts

Preventative Actions

Although there is no cure-all or specific medication for intergenerational trauma, there are preventative actions being put in place to counteract the negative responses. These preventative actions, such as youth centers, mental heath facilities, rehabilitation centers, intervention and after school programs, as well as donation centers are all viable sources that becoming more common in tribal communities and is a mark of Native tribes’ resistance and resilience. These measures show that the Lakota, among other communities, are still active and positive for their future as a sovereign nation and as proud Native Peoples. This type of resilience is a common factor in the Native lifestyle and encourages the production and reproduction of indigenous intelligence, as well as advocating for the investment in Native Peoples futures. The push towards a better future for the children and families is true representation of Lakota spirit.

Resources

Here are a few of the resources described above, specific to Pine Ridge Reservation and the surrounding areas:

- Conscious Alliance Conscious Alliance is non-profit organization dedicated to supporting Native communities by providing emergency food relief, empowerment programs for youth, and health education to Native American reservations, including the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Some of their programs on the Pine Ridge Reservation include:

- "Bring Nutrition Home" Backpack Program--Provides healthy food for children at Loneman School on the reservation. All students receive free or reduced lunch.

- Pine Ridge Learning Garden and Family Garden Programs--Teaches students at Pine Ridge School how to garden and provides fresh produce for families.

- Sustainable Housing Initiative--Partners with the University of Colorado and the Native American Sustainable Housing Initiative to improve housing options in Tribal communities

- Red Cloud Indian School Red Cloud Indian School provides many initiatives geared at the success of Native students and their families. These programs are designed to promote nourishment, education, and artistic outlets to brighten the future of Indian communities. Some of these initiatives include:

- Lakota Language Program--A program designed to bring back traditional Lakota language and culture by implementing comprehensive language curriculum in all grade levels and strengthening the community as a whole.

- Counseling Program--provides support and tools for students to overcome challenges and gain confidence in their own abilities. The counseling program conducts activities that promote self-confidence and self-respect. They work towards combating pressures from colonization and helping communities members cope. This program also works to prevent suicide and drug use.

- Oyate Teca Oyate Teca is a program that provides a safe and constructive environment for children that provides after-school programs, enrichment programs, as well as food and clothing distribution centers. The program provides education on gardening, cultural classes, and provides food during holidays and food scarcity periods. Oyate Teca also provides clothes during all seasons and runs events geared for families.Some of the projects that they lead include:

- Kyle Dam Park Project--a project that plans to build a park around Kyle dam, the goal is to improve recreational resources of the community.

- Gardening classes--Oyate Teca provides gardening classes to community members to bring healthy, fresh, and affordable food to the community. This project is also a way to foster community unification and stress the importance of Native cooperation together.

- Pine Ridge Reservation Oglala Sioux Tribe

- The Lakota Siouz Tribe: A Look at the Statistics

- U.S. Department of Agriculture: Elsie Meeks.

- Helping the Lakota People Heal from Historical Trauma

- Trauma may be Woven into DNA of Native Americans

- "Reeling from the Impact" of Historical Trauma

Further Reading

For more information and opinions on the topic of historical trauma, as well as the issues that the Lakota and other Native communities are facing, then visit: