Infant Mortality and SIDS

Aberdeen Indian Health Service Area

Clara J. Devota

Introduction

Infant mortality and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, or SIDS, has plagued Native American communities ever since systematic oppression by Western colonialism began. The Aberdeen Indian Health Service provides health care and public health monitoring for nineteen tribal communities across Iowa, Nebraska, and North and South Dakota, a region which continues to have some of the most alarming rates of infant loss within the United States. The broad spectrum of Infant Mortality is categorized into three subsections: Neonatal Infant Mortality (0-28 days), Post-Neonatal Infant Mortality (28-365 days), and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. The SIDS epidemic lies not in death of neonates, but in death during the post-neonatal period of one month to one year of age. SIDS is the sudden and unexpected death of a seemingly healthy baby. The list below presents Infant mortality rates as the number of deaths per 1,000 live births (EagleStaff et al., 2006):

Neonatal Mortality

U.S. All Races = 4.6

Aberdeen Region = 5.6

Post-Neonatal Mortality

U.S. All Races = 2.5

Aberdeen Region = 6.9

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

U.S. All Races = 10.7

Aberdeen Region = 18.1

SIDS is the sudden and unexpected death of a seemingly healthy baby and Neonatal and Post-Neonatal Mortality are characterized as deaths with known causes and/or circumstances (Randall et al., 2001). The alarmingly high rate of SIDS, which is nearly double the average for all U.S. races, is matched by the high rate of post-neonatal infant mortality. However, neonatal mortality amongst the Aberdeen tribal communities is less disparate at only 17% above the national average (EagleStaff et al., 2006). SIDS and Infant Mortality present a major public health issue for communities around the globe; however, these problems amongst the Aberdeen Native American communities add a layer of sorrow to an already existing barrage of poverty, chronic illness, and cultural perpetuation. This region is home to communities with the highest poverty rates within the United States and the world. Most notably the Ogala Souix Reservation at Pine Ridge consistently remains the poorest county within the U.S. and the living conditions of its residents serve to agitate the already elevated rates of SIDS and Infant Mortality among Native Americans (Howell et al., 1999). Despite these tragedies, the Indigenous communities of the Aberdeen area, in conjunction with the Indian Health Service, have taken initiative to remedy the high mortality amongst infants in the hope of creating a better standard of living and preserving Native American cultures through their youth.

The Causes

Neonatal Mortality:

Though the Infant Mortality and SIDS epidemic amongst these communities is evidenced primarily in infants within the post-neonate period, neonatal mortality is still much higher than the national average. The exact factors leading to neonatal death are still debated, but a primary concern has been pinpointed as complications during labor and delivery due to a high birth weight. Native American infants express much higher birth weights than their white counterparts, and this is due in part to the epidemic of diabetes amongst the Aberdeen Indian communities. Mothers classified as diabetic prior to pregnancy and those who develop gestational diabetes frequently give birth to larger babies, which can result in trauma to the child while moving through the birth canal (Schell and Gallo, 2012).Following birth, infants of diabetic mothers may have elevated levels of insulin in their blood, but no longer have the high glucose levels which can result in a sharp decrease of blood sugar levels, or hypoglycemia (Tennant et al., 2013). This hypoglycemia may become so severe that it causes seizures and death. Other causes of neonatal mortality are related to the prenatal period and the health of a mother throughout pregnancy. Drinking alcohol and smoking throughout pregnancy may stunt brain development resulting in infant death (EagleStaff et al., 2006).

Post-Neonatal Mortality:

Post-neonatal mortality, or death occurring from 28 to 365 days of life, relates to death with known causes such as congenital birth defects and infection (EagleStaff et al., 2006). This subset of infant mortality can be described as the “other” category. Due to the nature of post-neonatal mortality being a designation given to any death with known circumstantial and biological causes, definitive causes of the 276% higher mortality rate amongst the Aberdeen communities in comparison to the U.S. national average cannot be accurately defined (EagleStaff et al., 2006). However, researchers have speculated the reasons behind this high rate as being access to health care. An American Indian child born with a defect may lack the proper care to survive with the abnormality, thus the condition becomes fatal. Another failure of health care within the Aberdeen region is the lower rate of vaccination amongst residents, often a result of isolated communities lacking access to vaccines (Singleton et al., 2009). Young children are particularly susceptible to bacterial infections because their adaptive immunities have not yet been built, with the exception of some immunity provided in-utero and through breastfeeding. Without vaccinations, infants are more likely to fall prey to pneumonia, pertussis/whooping cough, and a host of other bacterial infections. These infections can also be spurred on by the poor living conditions endured by Indian communities of the Great Plains. Contaminated food and water sources, and abysmal sanitary measures provide breeding grounds for deadly bacterial. The Aberdeen Indian Health Service is the primary care provider for Native Americans of this region, but lacking funds and a vast and remote geographic landscape make it difficult for the service to provide vaccinations and health care for its nearly 100,000 constituents.Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS):

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, sometimes referenced as Sudden Unexpected Infant Death, has the highest rate of occurrence of infant mortalities in the Aberdeen Service Area at roughly 18.1 deaths per every 1,000 live births (EagleStaff et al., 2006). These unexpected tragedies have circumstantial causes often unknown or indeterminable, thus a high SIDS risk relates more to the socioeconomic demographics of a community than the innate biological risks of infants. Research has shown many factors can lead to sudden death among infants, and it is often the combination of multiple factors leading to a high incidence of SIDS. The list below provides a few possible causes for SIDS:

- Lacking prenatal support - Prenatal visits for expectant mothers amongst the Aberdeen regions are much lower than the national average, and this presents a multitude of factors which could relate to a high prevalence of SIDS. Prenatal doctor visits not only aid in monitoring the health of the fetus and mother, but also serve as great educational sessions for expectant parents. These visits supply information on subjects such as breastfeeding, infant care tips, and emergency preparedness. In individuals lacking this care, SIDS has become more prevalent as knowledge such as how to properly lay a child down to sleep, or the skills of how to identify if your child is acting unusual, perhaps signaling illness, are not obtained. The low occurrence of prenatal visits by expectant parents within the Aberdeen area is in part due to the great distance these individuals must travel to receive care, and this is worsened by the pervasive poverty amongst residents which makes travel nearly impossible (Oyen et al., 1990).

- Poor living conditions – As in post-neonatal mortality, poverty and a low socioeconomic environment can lead to SIDS (Randall et al., 2001). Living environments lacking sanitary water and food, as well as infestations by rodents are common amongst Aberdeen Indian communities. Diseases such as bacterial meningitis and vector-borne viruses are easily contractible by infants, and in some cases, can also be transferred from the mother to fetus in utero. Bacterial meningitis can kill adults in only eight hours, and this time frame is much shorter in infants, thus it is a probable cause for SIDS.

Image 3 - Family outside their home in Wounded Knee, S.D. (Nord, 2015)

Poverty also invokes stressors upon parents which can lead to neglect or parental aggression, resulting in SIDS (Randall et al., 2001). Alcoholism is common amongst the constituents of Aberdeen Indian Health Service, and intoxicated parents may forget to check on their infants, resulting in crib deaths via suffocation. Research has shown SIDS cases often occur multiple times in a single family (EagleStaff et al., 2006), which could be the result of chronic neglect by parents as a side effect of the stress and emotional taxation induced by severe poverty. Infants demand a large amount of physical and emotional attention which can push caregivers beyond a breaking point when already living in a difficult environment.

- Smoking - Smoking cigarettes is pervasive amongst Native Americans in the Aberdeen area, and smoking while pregnant is not uncommon. Smoking cigarettes while pregnant is tied to an increased risk of SIDS, as research shows sudden infant death is higher when mothers smoked during pregnancy. The biological reasoning for why this correlation exists is still uncertain, but smoking during gestation is believed to cause a number of respiratory related conditions in infants such as asthma. Smoking in the vicinity of or in a home with an infant is also dangerous to the child. If the cigarette smoke remains in the home and proper ventilation is not available, an infant is a risk of suffocating by smoke inhalation, often while sleeping (Iyasu et al., 2003).

The Cultural Toll

The death of a young child takes a great toll on families and communities regardless of culture, but infant mortality presents a deeper emotional and cultural loss amongst the Aberdeen Native American communities than most. The Northern Great Plains tribes place children close to the Great Spirit; thus, children represent a central tie to earth and ancestor (Randall et al., 2001). Every case of infant mortality depletes a community’s connection to their culture and life ways. In many facets, infant mortality has also put the communities of Aberdeen at odds with their modern cultural patterns. The habits of smoking and consuming alcohol which have become commonplace amongst Native American families, and become ingrained into Indigenous societies, are known causes of SIDS and infant mortality. To preserve the ties to their traditional beliefs, tribes have had to take action against aspects of their modern tribal cultures.

Fighting Against Infant Mortality

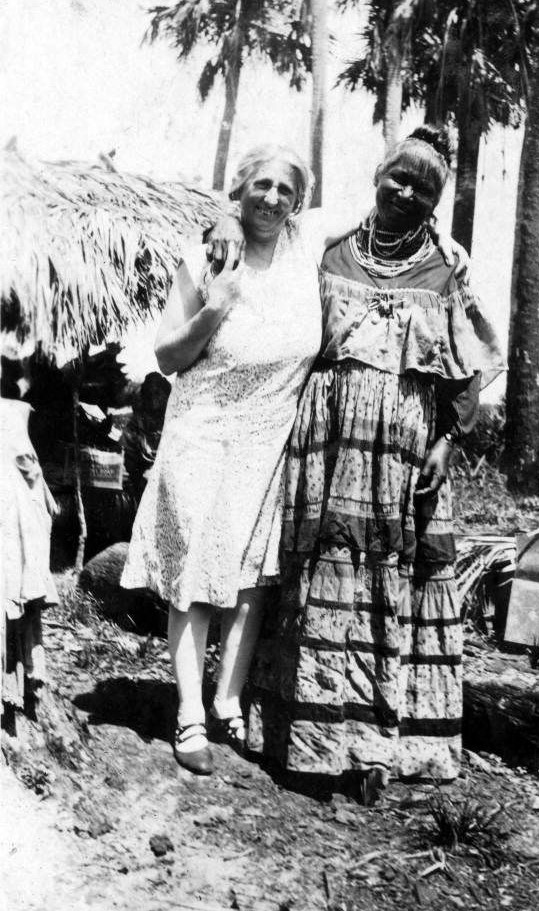

Since infant mortality was pinpointed as a public health concern amongst the Native American population, efforts to reduce infant death have occurred within the Aberdeen service area and nationwide. The first of these efforts took place amongst the Florida Seminole Nation in 1931 when midwives recently licensed by the state of Florida practiced in Florida Seminole communities to provide support to mothers and families with young children (Bigler, 1989). Whether this practice was effective is debatable as there are no comparative studies of infant mortality rates before and after the use of state midwives. The Aberdeen Indian Health Service Area did not see the use of outside health officials active in the community until the late 1970s, when the public health crisis of SIDS and infant mortality became more familiar to outside communities (Oyen et al., 1990).

Within the Aberdeen Indian Health Service Area, multiple education and parental support entities have come about to aid in reducing infant mortality and SIDS. Per the request of the Aberdeen Tribal Communities, the Perinatal Infant Mortality Review Committee, or PIMR, has been tasked with identifying the causative agents behind infant mortality as a method of solving the problem at its root (Randall et al., 2001). However, identifying the reasons behind infant mortality is only half the solution: the other half comes from community outreach and educational programs for Native American residents.

Since the late 1980s, smoking cessation programs have been set up throughout the Aberdeen region in an attempt to reduce the number of active smokers, particularly smoking in reproductive age women (Bulterys et al., 1990). This reduction in smokers then acts to reduce the cases of SIDS and infant mortality within the Norther Great Plains communities, and also improves the general health of the whole population. These cessation programs have been effective across many demographics in the United States (Windsor et al., 1985), but the question of if these programs correlated to a dropping infant mortality rate is still uncertain as the factors resulting in infant mortality are multivariate and complex.

References

Bigler, W. J. (1989). Public Health in Florida - Yesteryear (Vol. 1, pp. 7-19, Publication No. 3). Florida Journal of Public Health.

Bulterys, M., Morgenstern, H., Welty, T. K., & Kraus, J. F. (1990). The Expected Impact of a Smoking Cessation Program for Pregnant Women on Infant Mortality among Native Americans. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 6(5), 267-273. doi:10.1016/s0749-3797(18)30994-2

Eaglestaff, M. L., Klug, M. G., & Burd, L. (2006). Infant Mortality Reviews in the Aberdeen Area of the Indian Health Service: Strategies and Outcomes. Public Health Reports, 121(2), 140-148. doi:10.1177/003335490612100207

Howell, E. M., Zimmerman, B., & Closter, E. (1999). Infant Mortality Prevention in American Indian Communities: Northern Plains Healthy Start (Vol. 1, pp. 1-108, Rep. No. 1). Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Service Administration.

Iyasu, S., Randall, L. L., Welty, T. K., Hsia, J., Kinney, H. C., Mandell, F., Willinger, M., et al.. (2003). Risk Factors for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Among Northern Plains Indians—Correction. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(3), 303. doi:10.1001/jama.289.3.303

Oyen, N., Bulterys, M., Welty, T. K., & Kraus, J. F. (1990). Sudden unexplained infant deaths among American Indians and Whites in North and South Dakota. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 4(2), 175-183. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.1990.tb00636.x

Randall, L. L., Krogh, C., Welty, T. K., Willinger, M., & Iyasa, S. (2001). The Aberdeen Indian Health Service Infant Mortality Study: Design, Methodology, and Implementation. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 10(1), 1-20. doi:10.5820/aian.1001.2001.1

Schell, L. M., & Gallo, M. V. (2012). Overweight and obesity among North American Indian infants, children, and youth. American Journal of Human Biology, 24(3), 302-313. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22257

Singleton, R., Holve, S., Groom, A., Mcmahon, B. J., Santosham, M., Brenneman, G., & O’Brien, K. L. (2009). Impact of Immunizations on the Disease Burden of American Indian and Alaska Native Children. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(5), 446. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.44

Tennant, P. W., Glinianaia, S. V., Bilous, R. W., Rankin, J., & Bell, R. (2013). Pre-existing diabetes, maternal glycated haemoglobin, and the risks of fetal and infant death: A population-based study. Diabetologia, 57(2), 285-294. doi:10.1007/s00125-013-3108-5

Windsor, R. A., Cutter, G., Morris, J., Reese, Y., Manzella, B., Bartlett, E. E., Spanos, D. (1985). The effectiveness of smoking cessation methods for smokers in public health maternity clinics: A randomized trial. American Journal of Public Health, 75(12), 1389-1392. doi:10.2105/ajph.75.12.1389

Image References

Lakota Healthy Start. (2012, December 20). Miranda and Baby Jasper [Digital image]. Retrieved April 5, 2018, from https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/culture/health-wellness/lakota-moms-and-babies-need-help-support-lower-infant-mortality-through-healthy-start-program/

Manning, S. S. (2017, September 4). [Mother with child in a traditional cradleboard]. Retrieved April 9, 2018, from https://midwivesofcolor.wordpress.com/2017/09/04/native-baby-baskets-and-cradleboards-reclaiming-the-medicine-of-traditional-mothering-sarah-sunshine-manning/

Nord, J. (2015, December 20). [Ogala Sioux family outside their home in Wounded Knee, S.D. on the Pine Ridge Reservation]. Retrieved April 7, 2018, from http://www.capjournal.com/news/pine-ridge-sioux-seeking-new-federal-housing-funds/article_f5a43f1a-a75a-11e5-a9ad-338987908e5b.html

[Pine Ridge Reservation, Family bathing an infant]. (2012, April 21). Retrieved April 9, 2018, from https://popreflection.wordpress.com/2012/04/21/isolation-poverty-disease-and-destitution-native-americans-and-first-nations-in-the-united-states/

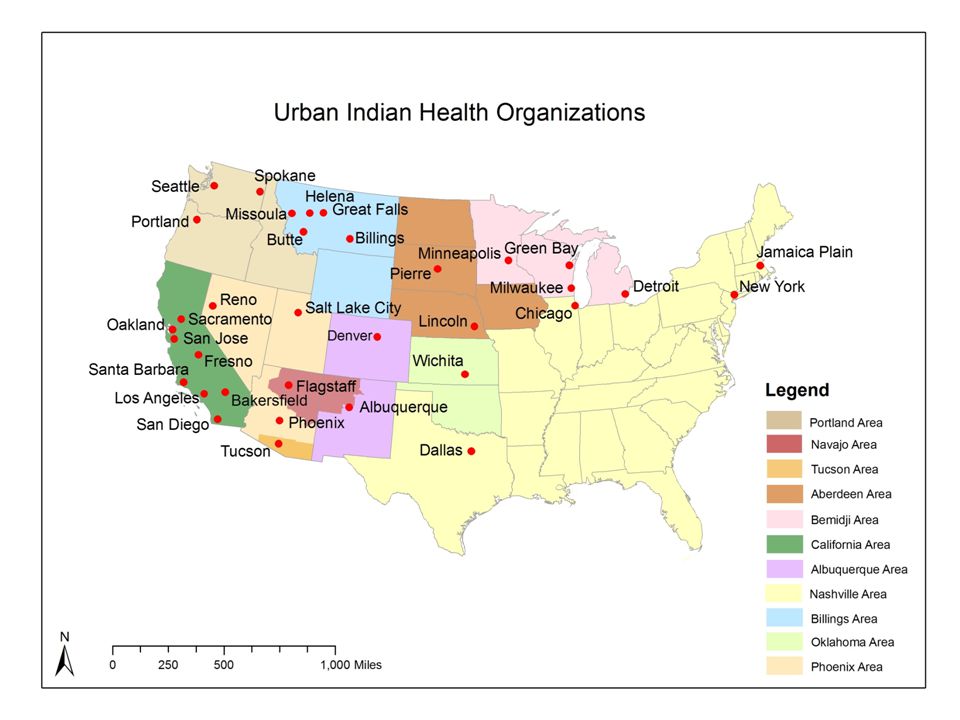

Thierry, J. (2008). Urban Indian Health Organizations [Map]. In Slide Player. Retrieved April 9, 2018, from http://slideplayer.com/slide/3142309/

Unidentified midwife standing with Susie Tiger at a temporary camp in Immokalee, Florida [Photograph found in Florida Memory, State Archives of Florida, Tallahassee]. (n.d.). Retrieved April 8, 2018, from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/44512 (Originally photographed 1931)

Image Links

Image 1 - Indian Health Service Regions

Image 2 - Sioux family bathing an infant on the Pine Ridge Reservation

Image 3 - Family outside their home in Wounded Knee, S.D.

Image 4 - Child in a cradleboard: A return to Indigenous motherhood traditions

Image 5 - Midwife standing next to Susie Tiger, a Seminole woman

Image 6 - Lakota Healthy Start Recipients, Baby Jasper and Miranda