Environmental Sustainability

The Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians

Molly Paquin

Environmental changes are threatening many facets of life for populations across the globe. American Indians are particularly affected by changes of environment. In the past, American Indian groups have been romanticized into exemplary stewards of sustainability. Today, with climate change threatening the way of life of numerous American Indian communities, some groups have become environmental stewards out of necessity. One example is the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians that was recently recognized as a national leader in sustainability.

Sustainability and the Environment

When considering sustainability and its relation to the environment, Tarah Wright (2002) has explored some of the prevailing themes of sustainable development widely accepted today. Among the many possible themes of sustainability (Wright 2002:218) highlights physical operations, research, environmental literacy, ethical responsibility, institutional cooperation, and industry partnerships. These themes are not all inclusive, and sustainability in itself is enveloped in ambiguity. Applications of sustainability vary widely, and these systems are accompanied with a range of possible effects on the environment, most of which still fall underneath the umbrella statement of sustainable. This can be problematic when discussing issues of sustainability and labeling specific actions, behaviors, or practices as sustainable.

Past Portrayals of American Indians and the Environment

Historically, American Indians have been used as symbolic images for sustainability through many aspects of Euro-American pop-culture. Anthropologist Renato Rosaldo (1989:69-70) uses the term “imperialist nostalgia” to explain the relationship that colonizers have placed on American Indians and the environment. This relationship is evident when looking at environmental education. William Stapp (1969:30) defines environmental education as “aimed at producing a citizenry that is knowledgeable concerning the biophysical environment and its associated problems, aware of how to solve these problems, and motivated to work towards their solution.”

One example of how American Indians are generalized and appropriated for Euro-American environmental education is the emergence of the Boy Scouts in the 1900s (Willow 2010). In an effort to return boys to a more “manly” state, the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) borrowed themes from many different American Indian communities as activities and teachings for young boys in the BSA program (Willow 2010:70). The appropriation of American Indian customs, practices, and ceremonies is evident in the photo of BSA members performing a ceremony at Camp Tichora in the 1950s.

This idealism of American Indian cultures and their relations as environmental stewards continued into other forms of environmental education. In the curriculum for Project Learning Tree (PLT), developed in 1976 for elementary education by the American Forest Foundation, three activities focused on American Indians (Willow 2010:76). These activities are problematic as they imagine American Indians as stewards of the Earth in a historical and often inaccurate setting. One activity includes a passage of text titled “Message from Chief Luther Standing Bear,” but it does not include any information stating where or when the quote was recorded (Willow 2010:78). This removal of historic accuracy further perpetuates the idealist imaginings of the existence of an “Ecological Indian.” Another problematic aspect of these PLT activities is in the context these American Indian communities are placed, or rather are not. In the teacher’s guide there are limited details about contemporary American Indian communities (Willow 2010:78). If this information was not relayed to students, the stereotype and misperception of how contemporary American Indian communities exist is left out of the educational sphere (Willow 2010). In this case, the use of American Indians in educational context is purely at the benefit of the non-native communities.

This is not to say that American Indians do not have an ecological stewardship relation to the environment. In fact, global research of indigenous people exposes a knowledge of the natural world in an ecological as well as cultural sense (Krech 2005:79). Over 900 generic and 1,700 specific plant types, and over 390 animal categories are identified in indigenous cultures (Krech 2005:79). The portrayal of American Indians and their relationship to the environment are not entirely off-base, but they do need to be kept in context, and avoid stereotyping or generalizing all cultures into one pan-Indian idea of an “Ecological Indian.”

The Need for Environmental Sustainability

Today, climate change is a massive ecological threat to many tribes (Whyte 2013). Culturally significant species of plants, animals, and even culturally significant landmarks are being lost to changes in regional climates and more frequent extreme weather events (Whyte 2013). Kyle Whyte (2013:519) defines the concept of sustainability through the term collective continuance, referencing the capacity for community member livelihoods to flourish into the future. The close relation of many American Indian communities and the environment is not an imagined one. In many cultures, relations with features of the land or across species are important (Whyte 2013). One example is the reliance on wild rice or native fish populations as a food source and economic resource. Another example is the reliance of crafters on specific species such as the Ash tree for the production of traditional basketry. The loss of Ash trees would therefore also lead to a loss in cultural knowledge of how to make baskets, as well as an economic loss for Ash basket makers. Whyte (2013:520) argues that “the ecological challenges of climate change threaten collective continuance by changing the contexts in which systems of responsibilities are meaningful.”

According to recent U.S. government studies, “because of existing vulnerabilities, Indigenous people, especially those who are dependent on the environment for sustenance or who live in geographically isolated or impoverished communities, are likely to experience greater exposure and lower resilience to climate-related health effects” (Global Change). Threats to nutritionally and culturally significant food items is a challenge facing many indigenous communities, the Ojibwe of the Upper Great Lakes Region mentioned specifically as an example (Global Change). Loss of cultural identity, water security, and degraded infrastructure are also factors contributing to the vulnerability of many indigenous populations in North America (Global Change).

With many communities facing these vulnerabilities with climate change the idea of the Ecological Indian is brought out of the past and into the present. Today’s Ecological Indian might be a product of pop-culture, but continues out of necessity.

The Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians

Acting as Environmental Stewards

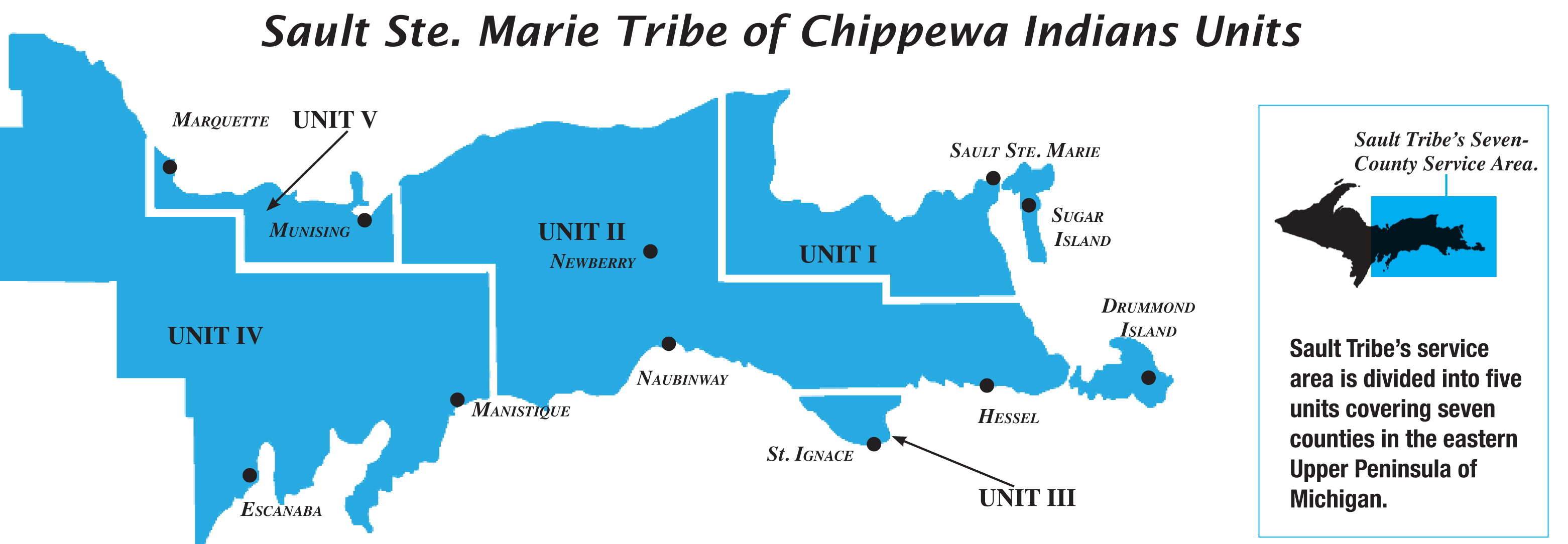

Many American Indian communities are finding themselves in the role of facilitating their own counteractions against the loss of native species, reduction of air and water quality, or the need to regulate wildlife populations. Individual communities are tackling the issues of climate change in their own ways. A good example of a group that has been working proactively against climate change is the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, or Sault Tribe. Located in Michigan’s Eastern Upper Peninsula, the Sault Tribe has a 7 county service area. The Sault Tribe has 44,000 members, and covers a large land-base within the state of Michigan (Sault Tribe 2016). The position of the Sault Tribe along the lakeshore of Lakes Superior, Michigan and Huron give the Sault Tribe a unique opportunity for environmental impact, as well as an increased level of vulnerability with the threats of climate change.

Sault Tribe Service Area

Sault Tribe Service Area

In December of 2014, the Sault Tribe was recognized by President Barack Obama as a Climate Action Champion at the White House Tribal Nations Conference (Indian Country Media Network 2014).

What is the Sault Tribe doing to earn this recognition?

All buildings under the Tribe’s control have been built with environmentally friendly construction methods. In recent years, all rental homes were updated and retrofitted for water, heating, and energy efficiency (St. Ignace News 2014). All vehicles used for the fishery department have been converted to run on recycled cooking oil rather than diesel fuels (St. Ignace News 2014). The tribe has a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 4% every year, and is researching the possibility of installing renewable energy sources such as windmills. Along with all of these tribal programs, the Sault Tribe is also partnering with local 4-H units to plant more trees and shrubs, and is developing a food waste recycling program (St. Ignace News 2014).

Aside from energy efficiency, the Sault Tribe also plays a large role in the management of fish and wildlife in the Eastern Upper Peninsula and the Straits of Mackinac waterways. The Sault Tribe has an Inland Fish and Wildlife Department. This department works in conjunction with the United States Forest Service to report harvest statistics, recommend harvest levels, conduct fish and wildlife population and habitat research, and represent the Sault Tribe on committees (Sault Tribe 2016).

The Sault Tribe also has an Environmental Department whose mission is “to protect the health and wellbeing of present and future members of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, by protecting the environment on which they depend” (Sault Tribe 2016). The Environmental Department has jurisdiction over the lands and waters in the 1836 Treaty Territory. This includes 21,621 square miles of land, and 17,000 square miles in Lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron (Sault Tribe 2014). They enforce rulings determined in conjunction with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

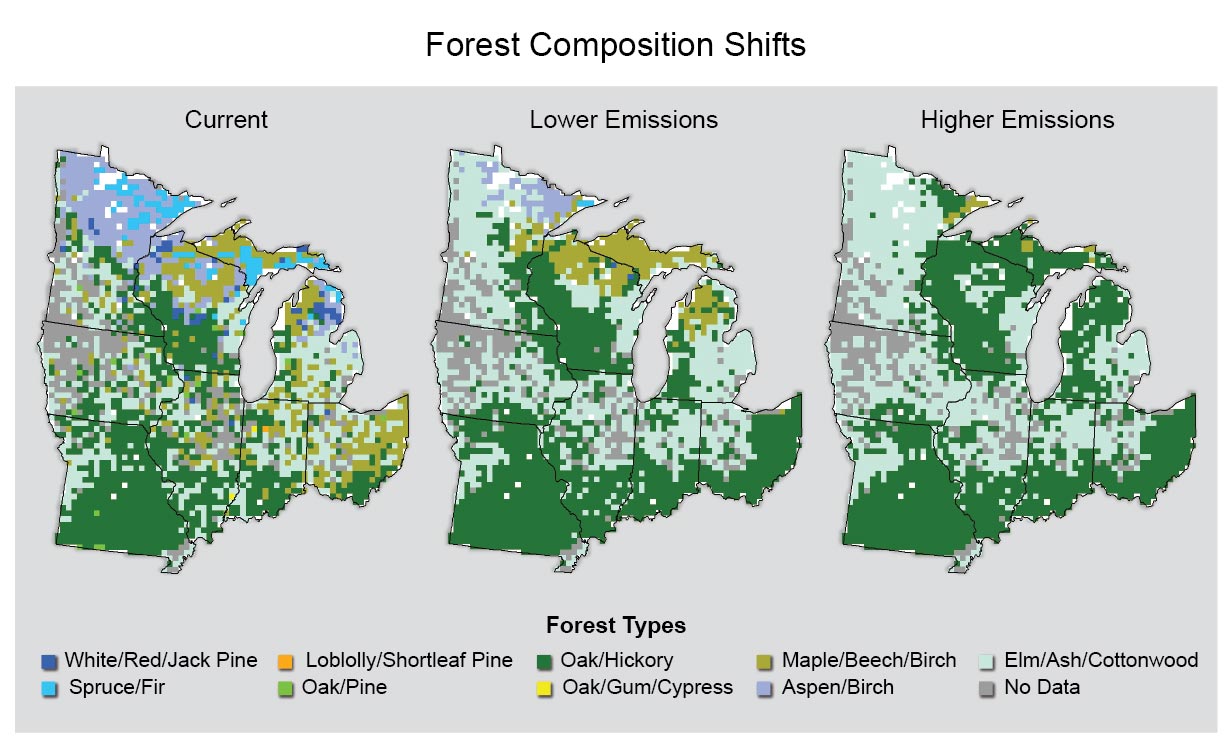

There are many environmental threats currently facing the Sault Tribe. Some of the main environmental concerns today include Line 5 Oil Pipeline, Chronic Wasting Disease, invasive zebra mussels, change in forest cover, and many more. The Sault Tribe is an example of what one community is doing to combat these issues, and does not speak for all nations.

Further Reading

indiancountrymedianetwork.com/environment

References

Global Change 2016 Populations of Concern. https://health2016.globalchange.gov/ accessed April 21, 2016.

Indian Country Media Network 2014 Obama Names Two Tribes Among 16 Climate Champions Nationwide. http://www.inctm.com/ accessed April 21, 2016.

Krech, Shepard III 2005 Reflections on Conservation, Sustainability, and Environmentalism in Indigenous North America. American Anthropologist 107(1):78-86. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3567675 accessed April 21, 2016.

Merriam-Webster 2016 Merriam-Webster Dictionary. http://www.merriam-webster.com/ accessed April 21, 2016.

Rosaldo, Renato 1989 Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis. Boston: Beacon Press.

Sault Tribe 2016 Story of Our People. http://www.saulttribe.com/ accessed April 21, 2016 2016 Inland Fish and Wildlife Department. http://www.saulttribe.com/ accessed April 21, 2016 2016 Environmental Department. http://www.saulttribe.com/ accessed April 21, 2016 2014 Inland Harvest Guide 2014. http://www.saulttribe.com/ accessed April 21, 2016.

Stapp, William, B. 1969 The Concept of Environmental Education. The Journal of Environmental Education 1:30-31. DOI: 10.1080/00139254.1969.10801479 accessed April 21, 2016.

St. Ignace News 2014 Tribe Earns Award. http://stignacenews.com/ accessed April 21, 2016.

Whyte, Kyle P. 2013 Justice Forward: Tribes, Climate Adaptation, and Responsibility. Climate Change 120: 517-530. DOI:10.1007/s10584-013-0743-2 accessed April 21, 2016.

Willow, Anna J. 2010 Images of American Indians in Environmental Sustainability in Higher Education: Anthropological Reflections on the Politics and History of Cultural Representation. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 34(1): 67-88. DOI:10.17953/aicr.34.1.413458lr22424615 accessed April 21, 2016.