Apsáalooke Language Revitalization and Preservation

Apsáalooke (Crow) Nation

Alaynna Dressler

Introduction

After centuries of cultural oppression and erasure by the establishment of boarding schools and forced assimilation, Apsáalooke has been officially classified as an endangered language. Many generations of Crow people have lacked proficiency in the language of their ancestors due to years of racist legislation passed by a settler-colonial government uninterested in the preservation of Indigenous cultures and languages. However, the Crow Nation is diligently fighting to save their language, their culture, and their connection with their ancestors. From the revival of the sacred Sweat Lodge ceremony as a means of cultural transmission, the establishment of the on-reservation Little Big Horn Community College, and the development of an Apsáalooke dictionary, this Indigenous group is currently doing everything they can to reclaim the culture that had almost been completely stripped away from them. For the purpose of this case study, the most important things to address is the history of the oppression of the Crow, modern-day cultural revitalization efforts, and efforts to preserve Indigenous languages.

History of the Oppression of the Crow

Ever since European arrival in the Americas, native peoples have had their ancestral homelands and traditional cultures stripped away from them to be replaced with the “standard” Euro-American settler culture. With the founding and subsequent expansion of the United States, more and more Indigenous communities were driven from their homes and forced to assimilate into American society. The Apsáalooke (Crow) Nation was particularly victimized, not just by the United States government, but other Indigenous communities as well. The Crow had an incredibly tense relationship with the nearby Lakota and Cheyenne. It is highly likely that this uneasiness was caused by American expansion. As groups like the Sioux and Cheyenne were driven from their ancestral lands, they were forced to move into the territory of the Crow. These tribes were constantly fighting each other for control of hunting grounds and other resources. Eventually, the Crow were forced to move up the Yellowstone River. The United States government got involved in this conflict and, through the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), declared that the Lakota Sioux had control over lots of ancestral Crow lands -- from the Black Hills to the Big Horn Mountains (Treaty of Fort Laramie 1868, Article V). With growing pressure from the Lakota, the Cheyenne, and the Americans, the Apsáalooke peoples had nowhere to go. On May 7, 1868, they sold about 30 million acres of their land and moved to an 8-million-acre reservation in southern Montana. Their tense relationship with the nearby Sioux and the amount of land that they sold to the United States told the federal government that the Crow would be easy targets for dispossession and assimilation. The Sioux Nation was incredibly strong and the United States tried to gain their favor by giving them legal rights to previously held Crow territories. They thought that doing this would make the Sioux easier to assimilate into American society. Of course, this is not true. In the case of the Apsáalooke people, the U.S. federal government figured that they would be able to take a more aggressive approach because they perceived the Crow Nation to be weak and unable to hold on to their land and their culture. This, just like the federal government's perception of the Sioux Nation, was incorrect.

Prior to and in the earlier years of the nineteenth century, churches would often set up schools on reservations to teach Indigenous children to speak English and convert them to Christianity (Nixon, 2015). On the Crow reservation, these missionary schools were known as "contract schools" (Holman, n.d.). In the mid-1800s, the United States government became more aggressive about assimilating Native Americans into the mainstream American culture and insisted that Indian children be sent to boarding schools several states away from where their homes were. By separating the children from their communities, they would “weaken family ties and destroy cultural traditions” (Nixon, 2015). This was the first step in destroying Indigenous cultures and assimilating American Indian peoples into American society.

Richard Henry Pratt opened the very first government-run Native American boarding school in the United States in 1879. It was called Carlisle Indian Industrial School and had an initial class of 136 students. Four years later in 1883, Indigenous families were threatened with starvation and poverty if they did not send their children to the boarding schools. There were six Crow children that were taken to Carlisle in 1883. They were:

- Charlie Fisher (Entered in February 1883 and died in September 1886; he was 17 and it is suspected that he died of injuries sustained during punishment for speaking his native language)

- Paul Jones (Entered in February 1883 and departed in June 1884)

- Edward Hears Fire (Entered in February 1883 and departed in January 1884)

- Charlie Foster (Entered in February 1883 and departed in departed in January 1884)

- Carl Leider (Entered in February 1883 and departed in January 1890; eventually went back to the reservation and used his knowledge of the English language to communicate the grievances of his people to the United States government)

- John Wesley (Entered in February 1883 and departed in April 1885)

Cultural Revitalization Efforts

On September 13, 2007, the United Nations adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This document declared that:

Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to designate and retain their own names for communities, places, and persons (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007).This policy was, for the most part, met with overwhelming support. However, it did encounter opposition from the four biggest settler-colonial countries -- the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. These four nations eventually changed their votes, but it is interesting to see how the people benefitting the most from settler-colonialism are the same people who voted against letting Indigenous peoples have cultural independence. In general, this document guaranteed legal protection to Indigenous communities when it came to practicing their traditional religions, speaking their traditional languages, and communicating their traditional histories and life philosophies.

The Crow Nation has been doing a lot to revitalize their culture. Lanny Real Bird talks about how the Apsáalooke have been trying to teach the younger generations to understand the importance of “horsemanship, family, ceremonial preparation, individual roles or responsibilities, discipline, cultural gatherings, and the respect for our elders and ourselves. This also includes formal teachings in informal settings regarding the universe, philosophy, traditional values, ethics, religion, and even disciplines in being competitive and resilient” (Real Bird, 2017). For the Crow, one of the main ways of transmitting cultural and ancestral information between elders and youngsters is through the Sweat Lodge ceremony. This is an incredibly important medium to communicate “prayer, healing, teaching, preparation, personal visions, storytelling, humor, role of clan reinforcement, and community missions” (Real Bird, 2017). Through the establishment of boarding schools and the removal of Indigenous children from their families, the Sweat Lodge ceremony and the passing of information between generations was threatened. This ritual has made an incredible comeback and is still practiced in Apsáalooke society as a way of transmitting cultural information between older and younger generations.

Preservation of a Language

In 1990, George H. W. Bush signed the Native American Languages Act (also known as NALA). According to Section 104 of NALA, it is the policy of the United States to:

(1) preserve, protect, and promote the rights and freedom of Native Americans to use, practice, and develop Native American languages; ...(3) encourage and support the use of Native American languages as a medium of instruction in order to encourage and support -- (A) Native American language survival, (B) educational opportunity, (C) increased student success and performance, (D) increased student awareness and knowledge of their culture and history, and (E) increased student and community pride; ...(6) fully recognize the inherent right of Indian tribes and other Native American governing bodies, States, territories, and possessions of the United States to take action on, and give official status to, their Native American languages for the purpose of conducting their own business;... (Executive Order No. Public Law 101-477, 1990).This was the first step in a long battle towards federal recognition of Indigenous languages and gave Native American communities the opportunity to reclaim the languages that had been stripped away from them. Since 1990, there has been a ton of legislation passed and social programs established to help Indigenous groups revitalize their languages.

Apsáalooke, the language of the Crow, has been officially classified as an endangered language. However, steps are being taken by members of the community to ensure that it does not go extinct. In 2011, efforts to revitalize the Crow language officially began. In order to get an idea of how at risk Apsáalooke was, the Education Department "assessed 304 children ages 3 to 5" (Pease, 2019). The results of this test revealed that, of the 4.5 and 5 years olds, 3.2% were fluent, "14% had limited fluency, 18% had understandinf/no fluency, 29% had limited understanding, and 36% had no understanding" (Pease, 2019). This drove Dr. Pease to write up a proposal asking to set up a language program for younger children. She was awarded with three years of funding to set up classes that would teach Crow children to speak the language of their ancestors. These classes are taught in Apsáalooke and "instills the children with a sense of pride in the Crow Nation history and Crow Nation culture" (Pease, 2019). In her article, Dr. Pease also included a list of the benefits language learners get from language revitalization:

- The children who attend these specialized language classes perform better on standardized tests than the children who only attend classes taught exclusively in English.

- Teaching children Apsáalooke at a young age allows them to communicate with their parents, grandparents, and siblings.

- Teaching children the Apsáalooke language helps them to estalish their identity and take pride in their heritage.

- Teaching children Apsáalooke "reverses the centuries' strong endangerment trajectory of [the] Crow language" (Pease, 2019).

The Little Big Horn Community College, which is located on the Crow reservation in Montana, also offers extensive courses in Apsáalooke. There has also been an increased usage of the language in on-reservation elementary and high schools. The Crow Nation is also in league with an organization called “Our Mother Tongues” that helps them organize and fund their language conservation efforts. About 85% of the 11,000 Crow peoples speak Apsáalooke as their primary language, but the elders are concerned about maintaining this fluency (Leffner, 2019). Because knowing the English language is necessary for success off-reservation, it can be hard for people to retain their bilingualism. As has been previously mentioned, there is also concern over whether or not Apsáalooke has changed linguistically since the establishment of boarding schools and the era of forced assimilation (Leffner, 2019).

Over the last few years, the Crow Language Consortium has been working extremely hard to preserve their language. One of their biggest accomplishments has been updating school curricula that have not been updated since the 1960s and 1970s and proving adequate and accessible materials to those studying Apsáalooke (Sukut, 2019). They, along with The Language Conservancy, started to work on "the Apsáalooke Dictionary Project -- Rapid World Collection (RWC), which... began in July 2018" (Pease, 2019). Dr. Pease has said that the "[Crow] dictionary has been a community effort that reflects our Apsáalooke culture culture and its unique attributes. For example, the Apsáalooke language is specific to the male and female language, addressing family members, even how words are pronounced" (Pease, 2019). It is still a work in progress, but they are hoping to get up to 20,000 words within the next year. They have been assisted by multiple people who are fluent in Apsáalooke, including numerous tribal elders. Wil Meya, a board member of the Crow Language Consortium and CEO of The Language Conservancy, said he believes that “the Crow language has perhaps the best chance of survival in North America” because of the number of fluent speakers that have helped to develop the Apsáalooke dictionary (Sukut, 2019).

Lanny Real Bird has been extremely involved in language revitalization efforts. He is a fluent speaker of Apsáalooke and teaches it at Little Big Horn Community College. One of his most important projects is the establishment of an immersion camp wherein children betwwen the ages of 11 and 17 are taught by tribal elders and fluent speakers how to speak their native language. These children have to look at each other when they are working on their pronunciation and overall speaking skills. According to David Brouwer, a journalist at the Billings Gazette, "leaders [of the Crow Nation] fear the language isn't being passed down to their children" (Brouwer, 2014). He has also been working on creating a variety of materials to help people looking to learn how to speak Apsáalooke. He has said he thinks the Western form of education -- such as textbooks and paper assignments -- does not help people learn to speak Indigenous languages. As a solution, he has developed CDs and flashcards to make learning the Crow language for students. He also believes that immersion camps are incredibly important because they make "the process fun for students and [they build] confidence" (Brouwer, 2014). He told Brouwer that "mistakes are embraced, not corrected" and that he is "trying to teach [the students that] the Crow language is a friendly place to be" (Brouwer, 2014). Dyanna Wilson, a member of the Montana Indian Language Preservation Pilot Program, explained that Lanny Real Bird's immersion camps -- "through the reenactment, activities and Apsáalooke lessons -- is trying to knit together the Crow's land, culture, and language" (Brouwer, 2014).

The Apsáalooke Language

Elements of the Apsáalooke language have made their way onto the internet in various forms. The Library at the Little Big Horn Community College has a whole webpage dedicated to teaching people about the Apsáalooke alphabet. There are also videos on YouTube that show tribal elders and those fluent in the language speaking Apsáalooke. In order to spread the knowledge I have gained and help the Crow people preserve their language, I will be including some information about the Apsáalooke language below.

The Apsáalooke alphabet looks quite different from the English language that most of us are used to seeing. It consists of the following characters (Library @ Little Big Horn College, 2002):

| Apsáalooke character | Pronunciation |

|---|---|

| a | available |

| aa | father |

| b | bed |

| ch | church (when at the beginning or end of a word) |

| ch | jail (when between vowels) |

| d | dog |

| e | bet |

| ee | able |

| h | half |

| i | bit |

| ii | beat |

| ia | area |

| k | kitchen (when at the beginning or end of a word) |

| k | guy (when between vowels) |

| l | leap |

| m | man |

| n | not |

| o | story |

| oo | abode |

| p | paper (when at the beginning or end of a word) |

| p | baby (wheen between vowels) |

| s | size (when at the beginning or end of a word) |

| s | zoo (when between vowels) |

| sh | shoe (when at the beginning or end of a word) |

| sh | pleasure (when between vowels) |

| t | time (when at the beginning or end of a word) |

| t | day (when between vowels) |

| u | put |

| uu | booed |

| ua | Nashua |

| w | way |

| x | acht (sounds like German "ch" sound) |

| ' | uh-oh (a glottal stop) |

There are also a number of Apsáalooke phrases that I was able to pick up from Crow Dictionary Online and I will share the most basic and important things that anyone who wants to learn Apsáalooke should know:

- Hello: Kahée

- How are you?: Shóotaachi

- Thank you: Ahóoh

- Mother: Ihkáa

- Father: Aksaawacheé

- Friend: Bachiialaxpé

- Native American: Akihchíssatbishe

- Yes: Éeh

- No: Baaleetáa

Conclusion

The era of boarding schools and forced assimilation was devastating to Indigenous communities all over the United States. Children were taken from their families and sent to institutions several states away from their homes. They were then forced to abandon their native religions and languages in favor of practicing Christianity and speaking English. In later decades, legislation was passed the allowed for the encouragement and protection of Indigenous groups and their efforts to revitalize their cultures. For the Apsáalooke people of the Crow Nation, it would be a long road. That does not mean, however, that important milestones have not been reached. From the revival of the Sweat Lodge ceremony as a medium of communicating cultural information between generations, the founding of the Little Big Horn Community College on the Crow reservation in Montana and full courses it offers in the Crow language, and the 20,000 word Apsáalooke dictionary that is currently in the works, this group has made tremendous headway in their efforts to reclaim their culture. Unfortunately, the Crow and the crucial steps they have taken toward self-determination and sovereignty are not recognized by the mainstream American public and is often overshadowed by the accomplishments of larger Indigenous groups such as the Lakota or the Navajo. Considering all the progress that the Apsáalooke people have made towards reclaiming their culture, it is incredibly important to recognize them and all that they have done.

Further Reading

For those that want to learn more about the history of cultural oppression and contemporary efforts to revitalize the Apsáalooke language and culture, these are great resources to check out:

- Reflections on Revitalizing and Reinforcing Native Languages and Cultures by Lanny Real Bird

- American Indian Education: A History by Jon A. Reyhner and Jeanne Eder

- Apsáalooke: The Story of the Crow Language by Nikolai M. Leffner

- A Dakota Family Remembers: Three Generations of Boarding School by Lance Nixon

Written Sources

Brouwer, Derek. 2014. “'Keep Speaking Crow to Me': Teens Immerse Themselves in Native Language.” The Billings Gazette. July 22, 2014. https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/keep-speaking-crow-to-me-teens-immerse-themselves-in-native/article_48708902-5da1-520e-87fb-30e46e8c981e.html.

“Crow Dictionary.” 2019. Crow Dictionary. Crow Language Consortium . 2019. https://dictionary.crowlanguage.org/.

Holman, Peter P. n.d. “Unintended Consequences: How the Crow Indians Used Their Education in Ways the Federal Government Never Intended, 1885-1920.” Thesis, Montana State University. Montana State University. . Accessed April 17, 2019. http://www.montana.edu/history/documents/papers/PeterHolman.pdf.

Leffner, Nikolai M. n.d. “Apsáalooke: The Story of the Crow Language.” Apsáalooke: The Story of the Crow Language | Environmental Studies | Lake Forest College. Lake Forest College. Accessed April 11, 2019. https://www.lakeforest.edu/academics/programs/environmental/courses/es368/leffner.php.

“Library @ Little Big Horn College.” 2002. Little Big Horn College Library. 2002. http://lib.lbhc.edu/index.php?q=node/127.

Nixon, Lance. 2015. “A Dakota Family Remembers: Three Generations of Boarding School.” Capital Journal. December 3, 2015. https://www.capjournal.com/news/a-dakota-family-remembers-three-generations-of-boarding-school/article_87ee46de-9a42-11e5-a764-1b7948fd098c.html.

Pease, Janine. 2019. “Dr. Janine Pease on Revitalizing the Crow – Apsáalooke – Language.” First Nations Development Institute. First Nations. 2019. https://www.firstnations.org/news/dr-janine-pease-on-revitalizing-the-crow-apsaalooke-language/.

Real Bird, Lanny. 2017. “Reflections on Revitalizing and Reinforcing Native Languages and Cultures.” Edited by William Ruff. Cogent Education 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186x.2017.1371821.

Reyhner, Jon Allan, and Jeanne Eder. 2017. American Indian Education: A History. 2nd ed. University of Oklahoma Press.

Sukut, Juliana. 2019. “Crow Language Bowl Held at MSUB Powwow Discusses Language Revitalization.” The Billings Gazette. April 7, 2019. https://billingsgazette.com/news/local/crow-language-bowl-held-at-msub-powwow-discusses-language-revitalization/article_b293488e-766b-57dd-bc76-86cf214badc8.html.

Exec. Order No. PUBLIC LAW 101-477, 3 C.F.R. (1990), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-104/pdf/STATUTE-104-Pg1152.pdf.

“Treaty with the Sioux -- Brulé, Oglala, Miniconjou, Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Blackfeet, Cuthead, Two Kettle, Sans Arcs, and Santee -- and Arapaho, 1868.” Opened for signature April 29, 1868. Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, vol. 2, https://dc.library.okstate.edu/digital/collection/kapplers/id/26839 .

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. 2007. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. United Nations. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N06/512/07/PDF/N0651207.pdf?OpenElement.

Image Sources

Image 1: Flag of the Crow Nation.

Unknown. 2013. Flag of the Crow Nation. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_the_Crow_Nation.svg.

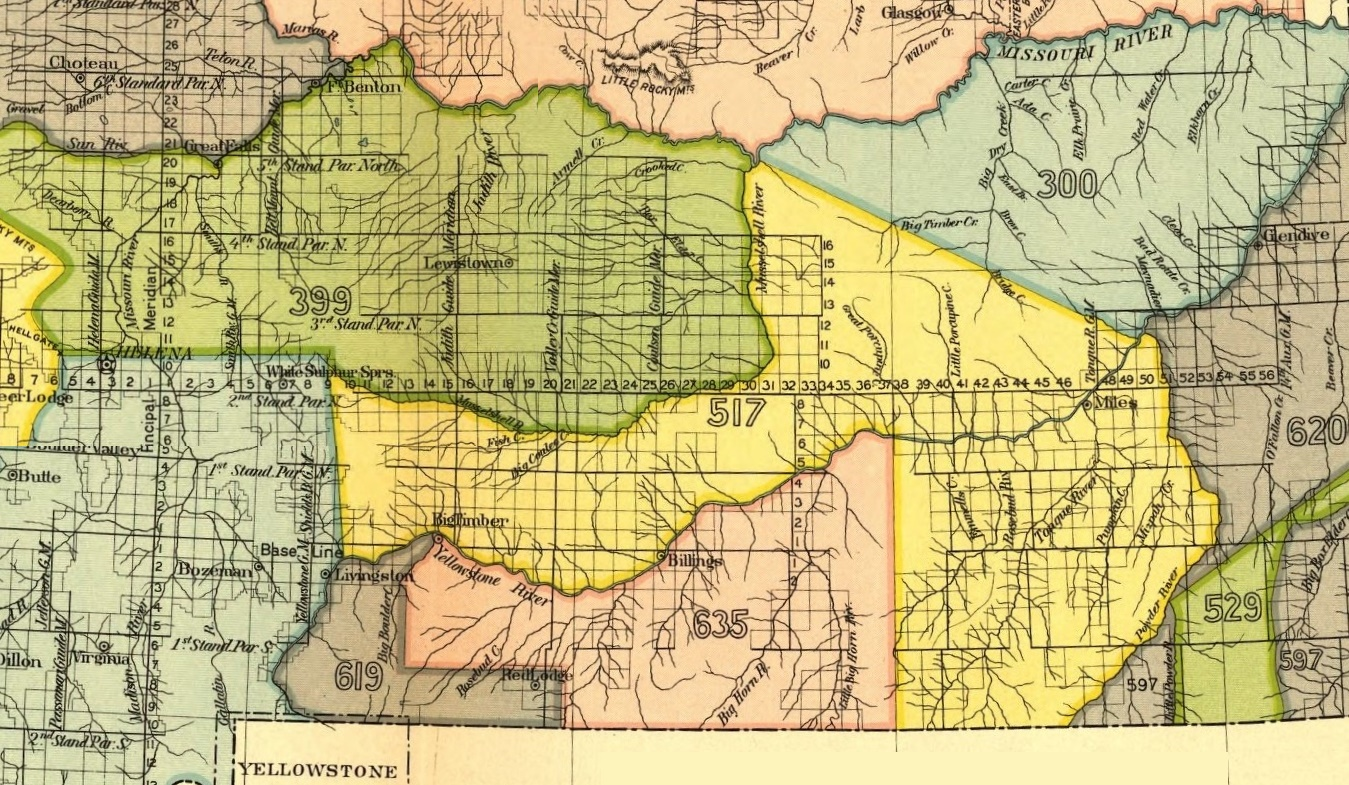

Image 2: Crow Indian Reservation According to the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

Crow Indian Reservation, Royce, Charles C, and Cyrus Thomas. 1896. “Indian Land Cessions in the United States, Montana I.” Map. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3701em.gct00002/?sp=39.

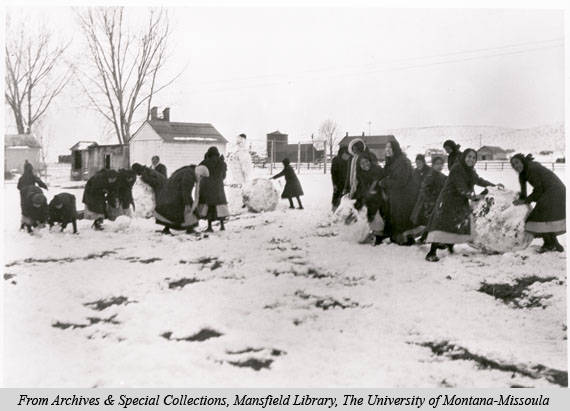

Image 3: Crow Indian Girls at Boarding School.

Harrison, William Harvey. 2009. Crow Indian Girls at Boarding School . Photograph. Montana Memorial Project. Missoula: University of Montana. University of Montana. https://mtmemory.org/digital/collection/p16013coll27/id/1279/.

Image 4: The Sign of the Crow Nation.

Buehrer, Lealan. 2017. A Welcome Sign in Crow Agency, Montana. Photograph. Air National Guard. Crow Agency: United States Air Force. https://www.ang.af.mil/Media/Photos/igphoto/2001783642/

Image 5: The library at Little Big Horn Community College.

Little Big Horn College. 2002. Photograph. Library @ Little Big Horn College. Crow Agency: Little Big Horn College. Little Big Horn Community College. http://lib.lbhc.edu/index.php?

Image 6: Crow Students Learning Apsáalooke with Lanny Real Bird at the Apsáalooke Language Camp.

Woodcock, James. 2014. Apsáalooke Language Camp. Photograph. Billings Gazette. Billings. https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/keep-speaking-crow-to-me-teens-immerse-themselves-in-native/article_48708902-5da1-520e-87fb-30e46e8c981e.html.

Video 1: Lanny Real Bird and Fatima Bad Horse Speaking Apsáalooke

Real Bird, Lanny. "Crow language video 1". Filmed [2004]. YouTube video, 21:31. Posted [August 2018]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XHHUhU0kTsg&t=0s.