Art, Representation, and Appropriation

Navajo Nation

•Chloe E. Wilson•

Introduction

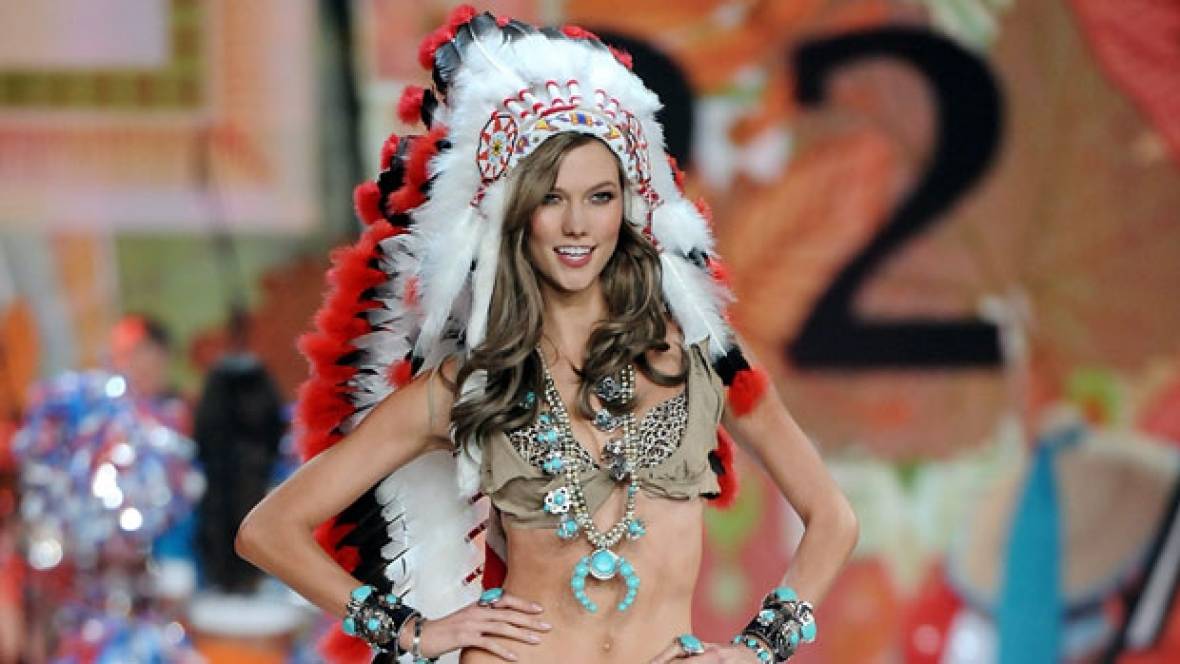

The Native tribes of the United States remain largely invisible to outsiders. We often are shown or imagine a stereotype, rather than the reality of Native peoples and their lives today. Their art, or rather imitations of their art, however, is seen in popular culture everywhere. It’s manifested on t-shirts, festival costumes, flasks – anything a typical American might be inclined to purchase. The fashion industry especially is guilty of playing off of Hollywood generalizations of Indians adorned in buckskin and feathers. The industry’s influence on American identity leads to this stereotyped image of Indians being the only image that we have, rather than the contemporary Native peoples and styles that are flourishing today.

The fashion industry is also guilty of cheaply replicating Native art and crafts for economic gain, which reduces true art and design to merely a type of brand for corporations to use. This has been seen in fashion shows in which models were trussed up in headdresses, and it’s been seen in the abundance of knock-offs and imitations that find their way into stores and trading posts. Many consumers don’t pay any mind to where their souvenirs are coming from or who made them, which is the cause of the invisibility that Native peoples are experiencing.

This webpage will detail the history of the traditional art of Navajo Nation, the art and crafts’ cultural significance, and a study of the misappropriation of such sacred art for the sake of capitalist gain. The Navajo have a rich, extensive culture which is very centered upon maintaining harmony on Earth. This page will also include information about and cases of misappropriation of Navajo art. The tribe’s art is widely popular and while replications are plentiful, these non-Native iterations appropriate the Navajo peoples’ very identities. Tips will also be included in this webpage concerning how to consciously purchase Native arts and crafts.

Historical Background

The Navajo creation story holds that the original Holy People, the Diyin Diné’é, were the first to generate artistic images using the material of the universe such as clouds, rainbows, and lightning. Since the creation of the universe, all iterations of such artistic images have been replications. The Diné, Earth People, came to their home lands after emerging through three other levels to settle on the fourth.

The number four itself plays a large role in Navajo culture as an organization principle. It can be seen in various elements of Navajo arts as well as in prayer and architecture. Even more, hózó, a central ideal of Navajo culture, is based upon four: harmony, goodness, wellness, beauty. This organizing principle is also reflected in components of Navajo Nation. In all four directions, there are four sacred mountains which were placed there by the Diyin Diné’é. They taught Earth People the right way to live. Earth People became integral to the order of the universe, so they were taught to do everything to maintain harmony on earth.

Traditional Navajo Art

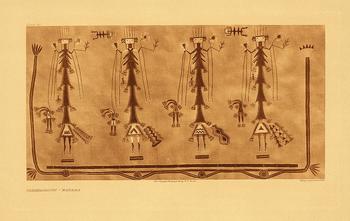

Sand Painting

The hataali, medicine men, use the four sacred colors in their sand paintings: white shell, turquoise, yellow abalone, and jet black. This particular form of art is one that is deeply tied to ceremony and tradition, and is wiped away after the ceremony is over. Since all original cultural images are always wiped away, any other form would be a mere imitation. However, corporations and artisans alike have produced permanently fixed sand paintings.

In Navajo culture, the images created by hataali are places where the Diyin Diné’é come and go. Different colored minerals and plant pollens are dropped to create anthropomorphic images of the Holy People within specific sacred locales of the past as told by the creation story (Berlo 2014). This is done for a patient who has sought physical or psychological healing. The patient sits within the sand painting and a specific chant is used to reestablish the correct relations between the patient and the forces that they depend on (Berlo 2014). This form of healing demonstrates the essentialness of the Diné’s connection to all other life.

Basket Weaving

Traditional Navajo baskets, ts’aa’, are used in the ceremonies performed by hataali. Their designs tell the story of harmony and balance between all living creations, making them highly sacred and symbolic objects (Berlo 2014). The baskets’ white, raised center portrays mother Earth, and white breaks from the center to the rim show the path of the Diné to this world. According to Navajo culture, a change in the design could represent a disruption in balance of the forces of life. Read more of Pete's work here: (Berlo 2014).

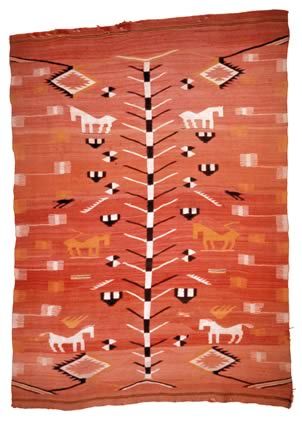

Rug Weaving

Rug weaving in Navajo culture is also linked to the Navajo creation stories. According to them, the spider woman Na’ashjéii wove the world into existence and taught Navajo the art of weaving (Berlo 2014). According to Lynda Teller Pete in here upcoming book, traditional rugs incorporate ch’ihónít’l, which connects the weavers energy, spirit, and creativity to the work. This spirit line also connects weavers to their next weaving (Pete 2018).

Bead Working

According to the Navajo creation story, beads were used to create the Diné by the Changing Woman, and used in a sacred manner today, the beads can represent power and completeness (Moore 2003). One sacred tradition called “Dressing the Mountains” uses beads of all sacred colors to dress the mountains sacred to the Navajo: Sisnaajinii to the East, Took’o’ooslííd to the West, Dibé Nitsaa to the North, Tsoodzil to the South, Dzil Náhoodilii, the Center mountain, and Ch’óol’į’į which is the Sacred Mountain.

The practice of dressing others in beads began with Changing Woman, who was the first baby to be adopted by the First Man and First Woman, wrapped in the first cradle, and washed first in a white bead basket. Changing Woman did the first of many things, and each of these things was commemorated with gifts of beads (Moore 2003). Because of this oral tradition, the Navajo to this day use beads in various sacred manners.

Issues of Replication and Imitation

Since all original Navajo images were created by the Holy People according to tradition, all others after, including those made using traditional methods by Navajo people, are replications (Berlo 2014). Due to the sacred nature of the images, these replications are the only ones that are ethical because they are created either in traditional ceremony, using traditional methods and materials, and often both.

The replication or imitation of Native art in non-Native contexts is problematic for two main reasons. First, replication by non-Natives essentially rips off the intellectual property of Native artists. Replications are partly the result of globalization as there has been a large increase in cultural trading and learning (Brantmeir 2007). The second issue with replication specifically of Navajo art is that the culture ties so many sacred meanings and purposes to their images that it’s almost dangerous to replicate. In the mid 20th century, ethnographer Maud Oakes was only able to make sketches of the rituals she observed through her sketches and herself being blessed in order to be properly aligned with spiritual forces (Berlo 2014).

Imitations by non-Natives are rarely culturally accurate. Dominant cultures notoriously have misappropriated more than just art since the colonial period. This misappropriation commodifies, sexualizes, and perverts rich cultural traditions into a Western imaginary isn’t representative of Native cultures.

Groups and Regulations

Native people own the rights to images that are specific to their family or tribe, which is most important in conflict over representation. In more recent years, there has been much more proprietary regulation regarding the use of Native images in non-Native contexts (Berlo 2014). This is due to the sacredness of Native art and designs.

American Indian Arts and Crafts Act

The American Indian Arts and Crafts Act maes it illegal to display or sell and product in a way that wrongly suggests that it’s produced by Natives, or the product of a particular Native individual, tribe, or organization (Indian Arts and Crafts Board 1990) However, the act isn’t able to protect lucrative products like mass-produced commodities. Furthermore, clothing designs are not copyrightable in the US in general (Indian Arts and Crafts Board 1990). This is more problematic for Natives than other due to the nature of the modern day cultural imperialism.

Trademark Law

Navajo Nation has taken advantage of the Trademark law, with ten registered trademarks of its name (The Fashion Law 2016), making the use of the name Navajo illegal unless within Native context. This is how Navajo Nation won their lawsuit against Urban Outfitters when the corporation introduced multiple products with the Navajo name in their descriptions. Most notable in the lawsuit and most offensive were the Navajo Hipster Panties.

A Western Cultural Lens

The purpose of this website is to say that despite the complex and extremely culturally important nature of Navajo art, the is a reason why it’s appropriation is so prevalent in Western societies, particularly the United States. Average Americans are influenced by the popular culture that permeates their everyday lives. Popular culture is generally seen as typical things such as television, music, the news, and the internet. In harsh reality, it’s influenced by corporate greed and manipulates consumerism, thereby manipulating the consumer (Storey 2010).

Generally speaking, Americans receive no formal education on American Indian cultures, if any education at all. The American imaginary has been shaped over time to perceive no more than stereotypes and generalizations. A major influencer of pop culture, the fashion industry, plays into this a great deal. Perhaps it’s in the spirit of cultural appreciation, perhaps it’s in the spirit of ignorance, but this industry in particular has contributed a lot to the appropriation of Native art and designs by producing commodities that sexualize and pervert their traditions.

Appropriation in American culture appears to be very selective, only choosing traditions or imagery that is recognized in stereotypes, thereby playing off of and contributing to Western popular culture. Since popular culture is one of the primary means through which individuals participate in and transform culture (Storey 2010), this is how American exposure to Native cultures becomes distorted into generalized viewpoints.

Case Study

The court case between Navajo Nation and Urban Outfitters ultimately began with an open letter written by Sioux Nation member Sasha Brown, stating her disgust with the store’s line of products that are offensive to Native peoples’ all over. The stores had around 20 different products using the name Navajo even though the tribe itself has various trademarks on the many derivatives of their name. The Navajo Hipster Panty, Navajo Print Fabric Wrapped Flask, Peace Treaty Feather Necklace, and the Staring at Stars Skull Native Headdress T-shirt according to Brown are not just uneducated but inherently legitimize the racism that they are promoting (Brown 2011).

The open letter, addressed to the CEO of Urban Outfitters Glen T. Senk, gained enough public attention from both Native Americans and European Americans that Navajo Nation formally filed a cease-and-desist letter. For Navajo Nation, this was more than a broken Trademark law. The case and its outcome would set the precedent for all other such cases afterwards (Sanchez 2016). Relegating Native peoples to, first, a generalization and second, a thing of the past has distinct implications. It’s been characterized by many as the next step after actual genocide and later, cultural genocide.

“It’s an issue when you have indigenous peoples…who have been subject to actual genocide, and then you come back around with what some people characterize as cultural genocide. The pillaging of land, the pillaging of personal property, followed by the pillaging of what could be considered intellectual property. It’s something that occurs against a background of a lot of other offensive actions” (Scafidi 1968).

The prevalence of these detrimental types of actions by large corporations is so widespread that Native tribes almost have no choice; at this point it’s the most effective way to fight against misrepresentation and misappropriation (Keene 2011). Since the original basis for Navajo Nation’s lawsuit was the Trademark on their name, Urban Outfitters retaliated with claims that Navajo was actually a generic term used by many stores, and the district court judge dismissed Navajo Nation’s claims, although Urban Outfitters and other related stores still faced counts on false advertising, trademark infringement, and unfair competition (Pangburn 2016).

In simplest terms, without regard even to the legal claims that the Navajo rightfully made, the large franchise’s use of the Navajo name was a blatant case of the big buzzword, cultural appropriation. The phrase, which has seen a lot more use in popular culture, can be defined as "Taking intellectual property, traditional knowledge, cultural expressions, or artifacts from someone else's culture without permission" (Scafidi 1968). This can include any aspect of cultural expression. Moreover, cultural appropriation is most often done unto minority cultures. In the case of Native cultures, the reason cultural appropriation is so damaging is because it’s almost always paired with ignorance. To misrepresent a culture while knowing nothing of it’s history and tradition is the ultimate slap in the face, and many Natives feel this whenever confronted with popular culture, which is supposed to represent society’s collective interest.

Final Conclusions

Native tribes remain generalized and largley invisible to non-tribal members because popular culture, which is supposed to represent a society's collective interest, largely represents corporate interest instead. Popular culture, which influences those who consume it, has caused Americans in particular to assign American Indians to a category marked “Native” that contains mostly stereotypical imagery. By consuming and retaining the depictions they are shown, people often will extend stereotypes to the Natives that they come across in their daily lives.

This leads to the bastardization of Native cultures, particularly art, crafts, and design. While the Navajo creation story explains elements of all of their traditional artistic practices, the world only sees the Navajo Hipster Panty and models walking runways in headdresses. When these are the only representations that the world sees, Navajo culture itself becomes almost invisible to everyone besides those who participate in it.

References

Image Sources

3. Navajo People. Navajo Rugs. Retrieved from http://navajopeople.org/navajo-rugs.htm