Generation Z: Cultivating Indigenous Culture and Identity

Jenna Wood, Katie Morris, Camille Renault

Manitoulin Island

The Importance of Cultural Arts Education

For Indigneous youth, it is clear there is a connection between the development of personal/cultural identity and exposure to traditional arts and culture practices. Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron, is a cultural hub where multitudinous opportunities are accessible for Indigenous people of all ages, especially Indigenous youth, to partake in traditional practices in order to explore and cultivate the development of their identity as Indigenous peoples.

Introduction and a Brief History

Discovering one’s place in society is a journey that we all have to make throughout youth and into adulthood. Figuring out how to answer the question of who we are is difficult and different for every individual. It requires taking a look at the things we enjoy, the people we spend our time with, who we want to be in the future, and where our family comes from. Though it sounds simple, certain groups, especially minorities including Indigenous peoples, have to approach these questions with a different perspective. Throughout history they have continuously had their place in society and validity questioned and attacked by majority groups. This fact only emphasizes the importance that they be able to connect with their traditions and cultural practices in order to aid in the development and cultivation of personal identities as well as identities within their culture and maintain a connection.

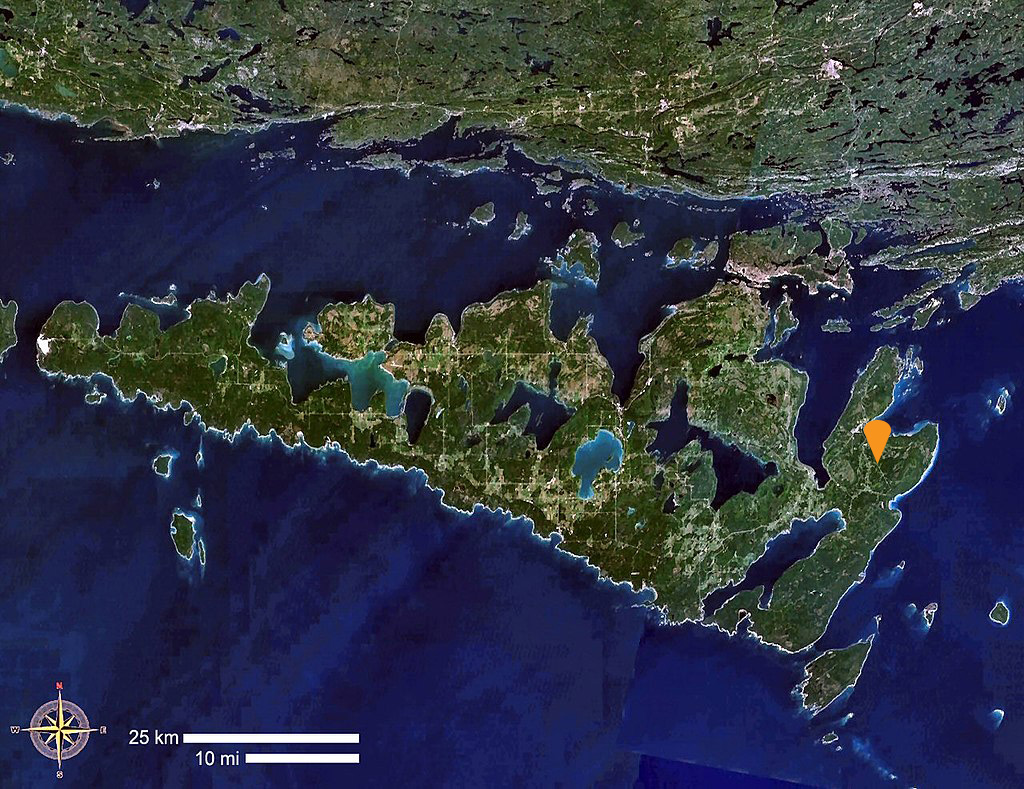

Located in the middle of Lake Huron in Ontario, Canada, Manitoulin Island is the largest freshwater island in the entire world. Manitoulin means "Spirit Island" in Anishinaabemowin and the Anishinaabe people (Anishinaabek) consider the island sacred. In 1836, the island was declared a refuge where native people would be able to live apart from “white civilization”. However, as is the story with many native lands, the Anishinaabek have gone through a lot to claim their place on the Island. In 1862, the government divided up the island to make space for non-native settlements, creating several different reserves in the process (Wikwemikong, depicted on Image 1). Now, Manitoulin Island is home to six Anishinaabek First Nations, 40% of the population comes from one of these. The island has become a cultural hub where multitudinous opportunities are accessible for Indigenous people, and especially Indigenous youth, to partake in such traditional activities in order to explore their identity as Indigenous persons. On the island there are many places to learn about Indigneous culture and practices including the Debajehmujig Creation Centre, the only professional theater on reserve land in Canada, Point Grondine Park, where one can participate in workshops teaching about traditional Indigneous medicine, and the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation which was created to preserve language, culture, arts, and traditions of the Anishinaabe people (Desnoyers-Picard).

The Role of Repatriation

In the reconnection process of communities with their cultural heritage, it is undeniable that patrimony has a role to play. The reappropriation of your own culture can be considered a necessary step in the determination of identity. In the Manitoulin Islands, the youth can benefit from a diversity of museums to learn about the Island’s habitants and history. While some of the island’s cultural items have never left their home, amount of others have been dispatched around the US and even the world as they were unlawfully taken away. This is where the repatriation effort begins. The Centennial Museum of Sheguiandah, home of reconstituted pioneer’s times, has recently (March 2020) added to its collection the repatriated war medals of Sergeant Clarence William Cook, born in Little Current. Part of a private collection, the whereabouts of the medals remained unknown until a coin dealer posted it up to sale on Ebay. A call to donations was made, allowing the medals to go back to the sergeant’s home country. Nevertheless, it is not every day that heritage items, especially from private collections, find their way home.

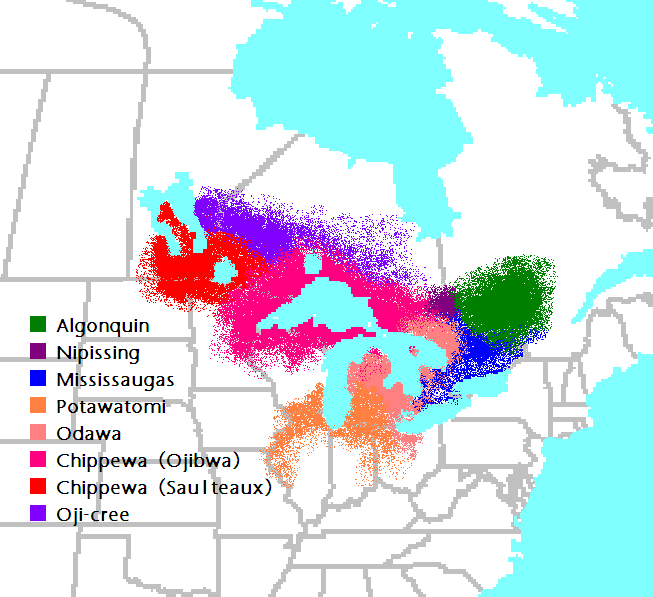

Indeed, not only does the access to diverse collection is still very limited but the wide dispersal of cultural items through the years has made their identification even more complicated. The Anashinaabek Nations’ situation is particularly complex as they have to face the legislations of two different countries in their repatriations processes. As efforts made towards repatriation of cultural object by governments is minimal, tribes have united to take actions in processes. One of them unites Michigan Anashinaabek nations in MAGPRA, who falls under the US Act of NAGPRA. They can so found themselves in intricate situations when presented to heritage items who’s provenance they can’t ensure is closer to one of Michigan tribes or one located north of the border and therefore unauthorised to examine the item. Facing all those challenges, Indigenous nations fight every day to defend their heritage.

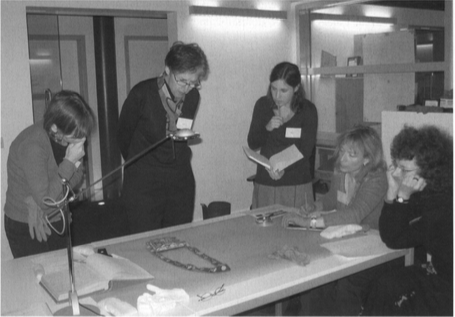

The generation Z knows it, the area we live in is one of technologies and sometimes, when barriers come between us, they can help us build bridges. When Aboriginal cultural centres and community-based researchers have faced systemic obstacles to accessing, borrowing, repatriating and exhibiting their own cultural heritage, "Digital Repatriation » is created. The Great Lakes Research Alliance for the Study of Aboriginal Arts an Cultures (GRASAC) is dedicated to the digital reunion of Great Lakes materials around the world, in order to put them back in relationship with community members. They namely collaborated with the Pitt Rivers Museum and British Museum, who, through a video call with Odawa elder Eddie King at the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation on Manitoulin Island, shared access to their collection, receiving in the mean time the knowledge Mr King wanted to share with the audience. Thus, even around the globe, efforts for diffusion and transmission of cultural heritage can and are being made, looking to share and gain knowledge. This can leave us hopeful that with evolving technologies and growing consciousness, the future will always learn more about the past and succeed to raise awareness.

Revitilization as a Community

The role of the youth is critical in these tough times for indigenous communities. It is important to teach them their connection to the Mother Earth and their culture while they are first learning how to perceive this world. On Manitoulin Island, one way to encourage this connection for the youth is through the Great Lakes Cultural Camps. These camps have eight locations throughout the Great Lakes region, and the camp location on Manitoulin Island is depicted on Image 1. This camp focuses on incorporating cultural practices within their outdoor adventures and activities. These cultural practices change throughout the year due to the seasonal harvesting of meat, medicines, and other natural beings.

By learning these skills as a youth community, it encourages them to work together and to rely on each other to overcome large projects and obstacles. An example of a long-term project that these youth work on is building wiigwaasi jiimaan (a birch bark canoe). Birch bark is a very light, waterproof and versatile material that Woodlands Indians used for their dwellings and for their canoes. Wiigwaasi jiimaan includes a process of gathering birch bark and spruce root. For wiigwaasi jiimaan, the birch is ideally harvested in the summer after a few days of rain. This is when the trees are flowing internally, and it is easier for the bark to be stripped from the tree. (Different projects require the bark to be harvested at different times of the year.) Much of this material is required, so it is necessary to have community involvement for the transportation of this wiigwaasi (birch bark) back to the work area. This practice of relying on each other to meet a common goal reiterates the importance of cultivating community as well as gives the youth the opportunity to find their connection and responsibility to the land.

The following video is a series of images produced by the Great Lakes Cultural Camps and shows the different types of activities and cultural practices that the youth are taught and participate in. These skills encourage the youth to connect to their cultural identity and teach them their responsibility to themselves, their community, their ancestors and to the Mother Earth.

Works Cited

The Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, The State of the Native Nations Conditions Under U.S. Policies of Self-Determination (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008)

Desnoyers-Picard, Sébastien. “Manitoulin Island, Ontario.” Indigenous Canada, 27 Aug. 2018, indigenoustourism.ca/en/manitoulin-island-ontario/

Barwin, Lynn, et al. "Methods-in-Place: “Art Voice” as a Locally and Culturally Relevant Method to Study Traditional Medicine Programs in Manitoulin Island, Ontario, Canada." International Journal of Qualitative Methods 14.5 (2015): 1609406915611527.

West, Allyshia. Indigenous and settler understandings of the Manitoulin Island Treaties of 1836 (Treaty 45) and 1862. Diss. 2010.

Peltier, Cindy. "An application of two-eyed seeing: Indigenous research methods with participatory action research." International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17.1 (2018): 1609406918812346.

"Opening Archives : Respectful Repatriation", Kimberly Christen, The American Archivist, Vol. 74 (Spring/Summer 2011) : 185–210.

"Digital Repatriation: Virtual Museum Partnerships with Indigenous Peoples" - Paul Resta, Loriene Roy, Marty Kreipe de Montaño, and Mark Christal, Conference: Computers in Education, 2002 IEEE.

"Decolonizing Museums : Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums", Amy Lonetree, University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

"Anthropology Now and Then in the American Museum of Natural History: An Alternative Museum", Emily Martin & Susan Harding, Anthropology Now volume 9 page 1-13, 2017.

"Great Lakes Cultural Camps", culturalcamps.com

Media Cited

Image 1, wikipedia.com

Image 2, wikipedia.com

Image 3, jstor.org Willmott, Cory, 10 Dec. 2007, Pitt Rivers Museum, Univ. of Oxford.

Video 1, youtube.com Great Lakes Cultural Camps Youtube Channel.