Semna South

Middle Kingdom: 12th Dynasty

Breana Peace

Introduction

Semna South is located along one of the narrowest parts of the Nile River, south of Wadi Halfa and north of Abri. The numerous excavations of Semna South have shown that this site includes a fortress that was likely used for trade along the Nile at the Second Cataract. There have been two significant excavations of this site, including the excavation by the Sudan Antiquities Service in 1956 and 1957, led by Jean Vercoutter, as well as by the Oriental Institute Expedition from 1966 to 1968, led by Louis V. Zabkar. The fortress at Semna South is known for its use in trade regulation along the Nile, specifically between Egypt and Lower Nubia in order to control Nubia and its goods. In addition to the fort found at this site, there is also a Meroitic cemetery, which was discovered to be home to many archaeological artifacts and human remains that allow archaeologists and anthropologists to gain insight into the lives of ancient Egyptians.

Introduction to location, geography, geology, setting, etc.

Located along the Nile River, the Semna South fort is less than a mile south of the larger Semna West fortress, both of which are located in between Wadi Halfa and Abri. (Zabkar & Zabkar) The site is believed to be a 12th Dynasty, Middle Kingdom fort used to control trade traffic along the Nile River. Semna South is a part of a collection of fortresses clustered about the Second Cataract. (Smith) These fortresses were mainly constructed under Senusret I in order to control trade with Lower Nubia, a major exporter of gold in the area. (Smith) During the Sudan Antiquities Service excavation, Vercoutter discovered a scarab and an offering table of Middle Kingdom origins, leading him to draw the conclusion that a Middle Kingdom settlement existed at the site, and was likely destroyed by a Christian population. (Zabkar & Zabkar)

Description of the Site

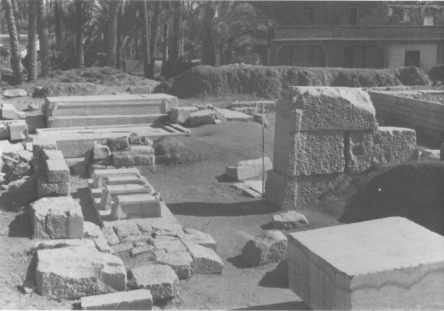

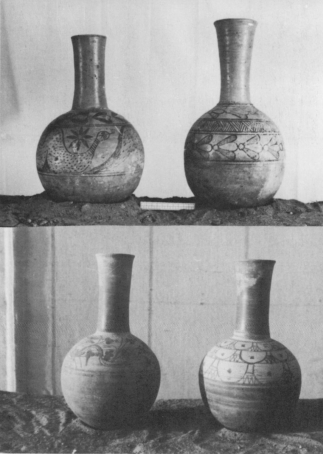

The site of Semna South is located less than a mile south of the larger Semna West fortress. (Zabkar & Zabkar) The site contains a fortress made up of a “stone paved glacis, an outer brick girdle wall, an inner ditch, and the main buttressed inner wall separated by the ditch by a berm or artificial terrace.” (Zabkar & Zabkar) The inner area measures at 34.3 meters by 33 meters, and includes a stone staircase. (Zabkar) This stone staircase was likely a Nilometer, a device used to measure the water level of the Nile during the flood seasons. The aforementioned inner walls were built in a square plan. The area on which the fortress was built was rocky and harsh due to the steep banks of the Nile River. (Alvrus) According to Zabkar’s reports, the fortress was also built on unusually low ground. (Zabkar) The second excavation of this site led to the discovery of a bank that connected the fort with a nearby hill terrace. This bank was a brick wall with stone reinforcements on either side. (Zabkar & Zabkar) The last section of Semna South that was formally excavated was the cemetery, located north of the fortress. (Zabkar & Zabkar) This cemetery included burials from both the Meroitic period and the Christian period, with similarities to typcal Egyptian burial styles in that the bodies were placed on their backs with their heads facing west. (Zabkar & Zabkar) Studies were conducted on many of the remains in this cemetery to assist in the determination of social structure in Egypt during this time. The cemetery did not exclusively contain human remains; many of the archaeological artifacts found at the Semna South site were discovered in the cemetery. (Zabkar & Zabkar) This included the discovery of pottery, tools, mirrors, and jewelry made from many different materials. According to Stuart Smith at the University of California Santa Barbara, the Semna South fortress provided housing and accommodations for a number of men that would be available to be of use for regulation purposes. (Smith) These men would oversee the passage of ships carrying cargo, and would assist in the transport of these goods to Egyptian vessels. (Smith) This was made possible through a ship harbor and a large plain, which was used as a staging area for caravans, who would be required to wait for permission from Egyptian officials to leave the area. (Smith)

Discussion of Excavations

While the forts surrounding Semna South were excavated as early as the 1920s, Semna South itself was not formally excavated until the late 1950s. This initial excavation, which took place in 1956 and 1957, was led by Jean Vercoutter and Sayed Thabit Hassan Thabit. (Vercoutter) A longer and more in-depth excavation was completed by Dr. Louis V. Zabkar at the Oriental Institute Expedition for the University of Chicago. (Zabkar & Zabkar) This excavation took place in the years 1966 through 1968, and provided a description of the layout of the site, specifically the fortress dimensions and features. It also drew on the previous excavation’s findings from the Sudan Antiquities Service excavation led by Vercoutter. Zabkar’s excavation was closely supervised by Dr. Gerhard Haeny in Kairo, an architect assigned to the site’s expeditions. (Zabkar) Daniel Hrdy’s study in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology focuses on some very specific findings from the excavations of Semna South: hair found from the burials. Using electrophoresis and fluorescence microscopy, Hrdy found that the hairs found in these Nubian burials were much more blond than one would have expected. (Hrdy) Another interesting set of research done on the remains from the cemetery in Semna South was the research done by Annalisa Alvrus on fracture patterns among the Nubians of Semna South. (Alvrus) This research was done on long bone and cranial fractures, and was done as part of the Oriental Institute Expedition for the University of Chicago. There are no current excavations of Semna South. In fact, after the Aswan High Dam was completed in 1971, the site was covered by the waters from this dam.

Results and Significance of Excavations

Zabkar’s excavation for the Sudan Antiquities Service revealed pottery in what was referred to as a dump at the site. The careful examination and translation of the words found on seal impressions in the pottery fragments give us what was likely the Egyptian name of the site: either “Subduing the Setiu-Nubians” or “the Subduer of the Setiu-Nubians.” (Zabkar) The findings in this dump were also crucial to the understanding of the ways that the Semna South fortress was able to communicate with other fortresses of its time at both the First and Second Cataracts. (Zabkar) Hrdy’s research into the hair found at burials in the Semna South cemetery led to the conclusion that the hair of these settlers was much lighter than previously thought in ancient Nubia. (Hrdy) These findings led to discussion about Nubian population during Meroitic and Post-Meroitic periods. This study also gave evidence that two of the hair samples were braided, lending insight into even a small part of home life in ancient Egypt. (Hrdy) The research done by Annalisa Alvrus allows us to examine the fracture patterns in the Nubians of Semna South, specifically in their long bones and cranial bones. (Alvrus) This research came from a sample of 592 individuals found in the burials at the Semna South cemetery, and was used to investigate things such as health status, interpersonal violence, and the effects of physical and social environments on trauma incidence. The findings of this study concluded that many of the fractures were from the physical environment, such as falling along the previously mentioned steep banks of the Nile River. (Alvrus) However, other fractures – specifically the high frequency of craniofacial fractures – led Alvrus to believe that this Nubian group experienced social stress which “could have precipitated or intensified interpersonal violence.” (Alvrus) This includes parry fractures found in many lower arm bones, showing signs of violence and self-defense. (Alvrus) Currently, the human remains found at Semna South are kept at Arizona State University, while the archaeological artifacts are kept at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute and are able to view by the public.

Conclusion

The fortress at Semna South was a 12th Dynasty, Middle Kingdom fortress designed by Senusret I to regulate trade along the Nile River at the Second Cataract. The fortress communicated with other fortresses of its type in order to allow Egypt to acquire more gold and more control over Lower Nubia. There were two significant excavations of Semna South, leading to many studies that allow us to look at the ways that Egyptians lived during the 12th Dynasty. This site is incredibly important in understanding the political structure of Egypt during the Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate Period, as it shows the ways that Egyptian rulers exercised their control over Lower Nubia. Aside from the fortress at Semna South, there is also a cemetery with both human remains and archaeological artifacts such as pottery and tools. There have been many significant studies since these excavations that enable archaeologists to look into things such as interpersonal violence and hair color among Egyptians during this time. The excavations of Semna South have given the world a better image of ancient Egypt.

Sources

Alvrus, Annalisa. "Fracture Patterns among the Nubians of Semna South, Sudanese Nubia." International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 9.6 (1999): 417-29. Web.

Hrdy, Daniel B. "Analysis of Hair Samples of Mummies from Semna South (Sudanese Nubia)." Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 49.2 (1978): 277-82. Web.

Smith, Stuart Tyson. "Askut and the Role of the Second Cataract Forts." Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 28 (1991): 107. Web.

Vercoutter, J. “Archæological Survey in the Sudan, 1955-57.” Sudan Notes and Records, vol. 38, 1957, pp. 111–117. www.jstor.org/stable/41710736.

Vercoutter, J. (1966). Semna South fort and the records of Nile levels at Kumma. Kush, 14, 125-164.

Žabkar, L. V., & Žabkar, J. J. (1982). Semna South: A preliminary report on the 1966-68 excavations of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute Expedition to Sudanese Nubia. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 19, 7-50.

Zabkar, Louis V. "The Egyptian Name of the Fortress of Semna South." The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 58 (1972): 83. Web.

Image Sources

Image 1: Žabkar, L. (1972). The Egyptian Name of the Fortress of Semna South. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 58, 83-90. doi:1. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3856238 doi:1

Image 2: Žabkar, L., & Žabkar, J. (1982). Semna South. A Preliminary Report on the 1966-68 Excavations of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute Expedition to Sudanese Nubia. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 19, 7-50. doi:1. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40000432 doi:1

Image 3: Alvrus, Annalisa. "Fracture Patterns among the Nubians of Semna South, Sudanese Nubia." International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 9.6 (1999): 417-29. Web.

Image 4: The Oriental Institute. Jar. Meroitic Period. Nubian Gallery at The University of Chicago, Chicago.

Image 5: Žabkar, L., & Žabkar, J. (1982). Semna South. A Preliminary Report on the 1966-68 Excavations of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute Expedition to Sudanese Nubia. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 19, 7-50. doi:1. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40000432 doi:1