Chickasaw Nation

Language Revitalization Programs

Chelsie Thomas

Introduction

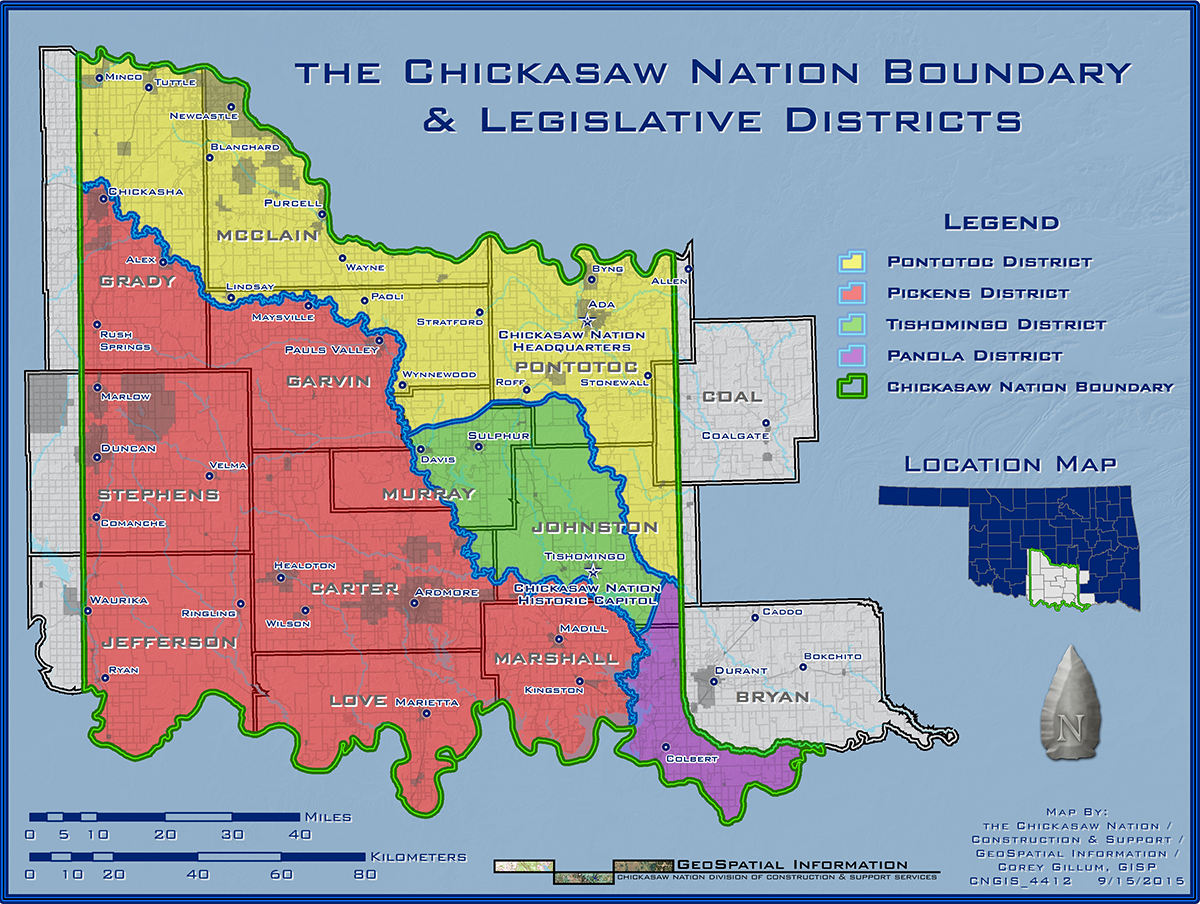

The Chickasaw Nation, one of the Five Civilized Tribes, has approximately 50,000 members and covers over 7,600 square miles within 13 counties of south-central Oklahoma (Davis 2016; The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation 4/16/16). Having been forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands in the southeast after the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Chickasaw suffered a great deal of cultural and linguistic loss. Currently, only about 70 fluent speakers of the Chickasaw language remain (Chew 2014). Seeing the impact this loss has had on its people, the Chickasaw Nation has implemented a number of diverse programs in an attempt to revitalize these ways of life (Francis 2010).

History

Originally settling in parts of Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama, the Chickasaw people were organized into an eleven clan matrilineal system (The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation 4/16/16). Each clan had a distinct purpose and place in the society. Many of the clans were known for their great warriors and potent medicine-men. The clan system created “a commitment to community, civic responsibility, and devotion to family” that strengthened the individual clans and the society as a whole (Fitzgerald, et al. 2006:13).

The Chickasaw people’s first encounter with Europeans occurred in 1540 with a group of Spanish conquistadors. Along with the help of other nearby tribes, the Chickasaw were able to successfully defeat the Spanish and push them out of their lands. As other European settlements began to build up around them, the powerful Chickasaw came to be respectfully recognized by many surrounding settlements. Trade systems were established with the French and the English. The Chickasaw community was actually able to thrive and grow during this time (The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation 4/16/16).

Soon, however, large amounts of Euro-Americans began to settle on Chickasaw lands. After many land concessions, the Chickasaw territory only remained in northern Mississippi. With the passing of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 by the U.S. Congress, Chickasaws, along with many other indigenous communities, were forcibly removed from their homelands and resettled in present-day Oklahoma. This removal affected more than the living situation of the Chickasaw people; their language and cultural practices were disrupted as well. The Euro-American presence in their territory led to an influx of bilingualism within the Chickasaw community. After this point, fewer and fewer Chickasaw parents were teaching their children the traditional Chickasaw language, leading to an overwhelming amount of monolithic English speakers (Davis 2016).

After establishing a Constitution in 1856 which disbanded the clan system and replaced it with a three-branch government much like that of the U.S., the Chickasaw were able to begin to rebuild their community. (The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation 4/16/16).

The Chickasaw Language

The Chickasaw language, part of the Muskegon language family, is a traditionally oral language. The language was passed from generation to generation in this way until it was decided in the 20th century that, in an attempt to preserve and better be able to teach the language to future generations, a dictionary should be written. In 1973 the A Chickasaw Dictionary was written by Chickasaw Jesse Humes and his wife, Vinnie May Humes. In 1994 Chickasaw: An Analytical Dictionary was written by linguist Pam Munro and Chickasaw Catherine Willmond. Each dictionary uses a unique alphabet, based on the same sounds (The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation 4/16/16).

Once Euro-Americans began settling in Chickasaw territory, the Chickasaw believed that it would be critical for the Chickasaw people to learn English in order to create strong economic and social relationships with the new settlers (Chew 2015). This led to a large amount of bilingualism among the Chickasaw people. Soon, the Chickasaw began to see their language as damaging to their relationships with Euro-Americans and, for the most part, stopped teaching their children the traditional Chickasaw language (Davis 2016).

Today, only between 70 and 75 Chickasaw speak the Chickasaw language fluently. In a total population of 50,000, there are very few members who are capable of teaching the rest of the nation the language (Chew 2014). Despite this very small number of Chickasaw speakers, the Chickasaw community still sees the ability to speak their language as a central part of their identity. Those who speak the Chickasaw language have a special place in the Chickasaw Nation and are very highly respected for their abilities (Davis 2016).

After the Native American Languages Act of 1990, the Chickasaw Nation began to extensively work to teach the Chickasaw language to more members of their community. This has presented itself in numerous programs which all approach language education in a unique way (Davis 2016).

Revitalization Efforts

The Chickasaw people see their language as a gift, given to them by their ancestors, and therefore something all Chickasaw are entitled to. Revitalization efforts have been created in order to help Chickasaw access this gift. The Chickasaw Language Revitalization Program was started by the Chickasaw Nation in 2007 in an effort to popularize Chickasaw language learning. In 2009, the Department of Chickasaw Language was founded as a part of the Chickasaw Tribal Government in order to fully incorporate language learning with Chickasaw governmental practices, thereby allowing for more funding and recognition (The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation 4/16/16).

Revitalization efforts have focused on making the Chickasaw language a defining aspect of Chickasaw identity and to recreate a connection of socioeconomic value with language fluency (Davis 2016). Language programs have also encouraged Chickasaw language learning to be a family affair, with linguistic responsibility being placed on parents, reestablishing the traditional methods of language teaching (Chew 2015). Current revitalization efforts include a Master-Apprentice program, youth language clubs and camps, community language classes, a Chickasaw language app, a television station, and internet-based programs for children (The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation 4/16/16).

The most successful of these programs is the Master-Apprentice program in which a fluent Chickasaw speaker is paired with a non-fluent, adult Apprentice. Through semi-immersion which takes place for 1-3 years and up to 20 hours a week, the Master teaches the language to the Apprentice in a non-classroom environment (Chew 2015). This technique was first used by Leanne Hinton with indigenous communities in California and was adopted by the Chickasaw Nation with the help of Hinton (Hinton and Hale 2001). The Master-Apprentice program works to create a conversational proficiency in its Apprentices. By doing this, the hope is that, once an Apprentice has completed the program, they will be better able to teach and communicate the language to other non-fluent speakers (The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation 4/16/16). The Chickasaw Nation expects that this program will be capable of generating up to 15 new semi-fluent speakers per year, with the potential for more growth once more speakers have become fluent (Chew 2015).

Other successful programs have been established at the local East Central University. The University offers four course levels which are available to students and to community-members. These courses are taught by fluent speakers and are seen as a way to get many Chickasaw able to participate conversationally in the Chickasaw language in a short period of time. Youth language clubs in the Chickasaw community work to get young people involved in Chickasaw conversation. These programs, which are often run through local schools, bring Chickasaw youth together to better understand the importance of language learning early in life in order to encourage Chickasaw language learning later on (The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation 4/16/16).

The Chickasaw community is currently working on improving their tribal television station to better incorporate language learning lessons and other cultural practices. The language learning app, called Anompa, is the first of its kind created by any tribal nation. Websites dedicated to teaching Chickasaw to children are also being improved. These methods work to bring Chickasaw language learning to as many people and as many different demographics as possible. The Chickasaw Nation hopes that by diversifying language learning, they will be able to better reach all members of their community (The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation 4/16/16).

The Future of the Chickasaw Language

Language revitalization efforts in the Chickasaw Nation are still considerably new. Though increases in the numbers of language-aware individuals are rising, it will likely take several more years, possibly decades, before the Chickasaw begin to see a substantial increase in the numbers of fluent Chickasaw speakers. Regardless of the current success rates, the efforts and measures being taken by the Chickasaw community in order to revitalize their language are innovative and progressive. New methods and programs are being established all the time within the community. The Chickasaw Nation is dedicated to seeing that their efforts be successful and to ensuring that the Chickasaw language lives on for many generations to come (The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation 4/16/16).

Works Cited

Written:

Chew, Kari A.B. "CHIKASHSHANOMPA' ILANOMPOLA'CHI." The Journal of Chickasaw History and Culture, 2014, 26-29.

Chew, Kari A.B. "Family at the Heart of Chickasaw Language Reclamation." American Indian Quarterly 39, no. 2 (2015): 154-79.

Davis, Jenny L. "Language Affiliation and Ethnolinguistic Identity in Chickasaw Language Revitalization." Language & Communication 47 (2016): 100-11.

Fitzgerald, David, Jeannie Barbour, Amanda J. Cobb, and Linda Hogan. Chickasaw: Unconquered and Unconquerable. Ada, OK: Chickasaw Press, 2006.

Francis, Mark. "Preservation Through Education." The Journal of Chickasaw History and Culture 12, no. 2 (2010): 52-61.

Hinton, Leanne, and Ken Hale. The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice. San Diego: Academic Press, 2001.

"The Chickasaw Nation." The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation. 2016. Accessed April 16, 2016. https://www.chickasaw.net/.

Images:

Image 1: The Chickasaw Nation Boundary & Legislative Districts. Digital image. The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation. September 15, 2015. Accessed April 16, 2016. http://www.chickasaw.net/Our-Nation/Government/Geographic-Information.aspx.

Image 2: The Great Seal of the Chickasaw Nation. Digital image. The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation. March 9, 2015. Accessed April 16, 2016. http://www.chickasaw.net/Our-Nation/Government/The-Great-Seal-of-the-Chickasaw-Nation.aspx.

Image 3: Anompa Language Learning App. Digital image. The Official Site of the Chickasaw Nation. February 3, 2016. Accessed April 16, 2016. http://www.chickasaw.net/Our-Nation/Culture/Language.aspx

For Further Reading

Gorman, Joshua M. Contemporary American Indians: Building a Nation: Chickasaw Museums and the Construction of History and Heritage. 2nd ed. University of Alabama Press, 2011.

Hinson, Joshua. "Growing Our Language." The Journal of Chickasaw History and Culture, 2014, 34-35.

Hinton, Leanne. "Language Revitalization and Language Pedagogy: New Teaching and Learning Strategies." Language and Education 25, no. 4 (2011): 307-18.